The Belt and Road Initiative 2020 Survey – A more sustainable road to growth?

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has continued to evolve and expand in its sixth year. Originally conceived to foster greater connectivity between China and the countries along the traditional Silk Route, the initiative has now become global in scale and ambition. More than 150 countries and organisations – from Latin America to the Pacific – have reportedly signed BRI agreements with China, and this vast new network of infrastructure, trade and investment is reshaping China’s engagement with the world.

A report released by German company Siemens at the World Economic Forum in January 2020 states that China is set to become the world’s biggest economy by 2030, in part due to the BRI helping China to expand its presence. BRI countries account for about 70% of the global population and more than 50% of global GDP. According to estimates, China will have initiated or completed BRI infrastructure projects worth a total of US$1.08 trillion by 2025.

This is not surprising. In April 2019, Beijing hosted the second Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation. The event sought to boost the intiative by setting out a clearer direction in the face of concerns around debt servicing, corruption, environmental impact and delays or cancellations of flagship projects. The aim of the Belt and Road Forum was for China to reassert its commitment to the flagship foreign policy initiative, address major challenges and demonstrate a greater willingness to adopt a more inclusive approach moving forward. China also stressed the practical benefits of the BRI for participant countries at a time when globalisation is fraying and US leadership has come under greater scrutiny.

During the forum, President Xi Jinping outlined four key pillars to support the BRI in years to come – finance, transparency, the environment and inclusivity. One of the biggest achievements of the forum was the commitment to create a debt sustainability framework to improve the assessment of financial risk associated with projects. The guidelines build upon those released in late 2018, which looked to enhance BRI project standards and quality, as well as discussions on improving financial governance.

The measures strongly indicate the effort being made to strengthen the institutional underpinnings of the BRI. This, in turn, may help to reduce concerns expressed by some international parties that China has engaged in a form of ‘debt-trap diplomacy’. Despite the recent first-stage trade agreement between the US and China, there are still risks that outstanding issues could result in further protectionist policies that may further disrupt trade and investment patterns. As a result, the BRI could become increasingly more important for China and member countries as they look to restructure supply chains and adapt to shifting trade patterns.

Key findings

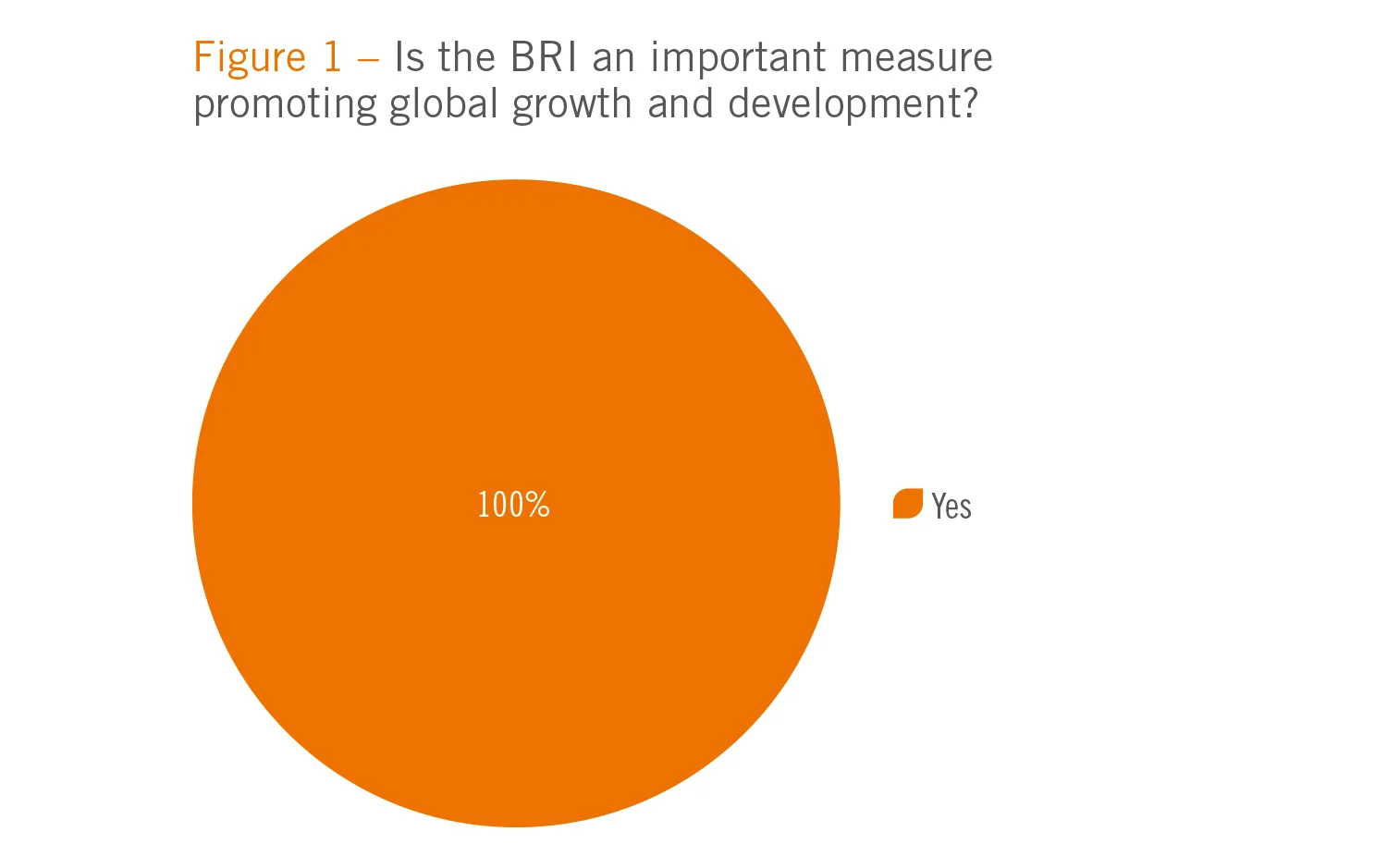

- All respondents to the survey view the BRI as important in promoting global growth

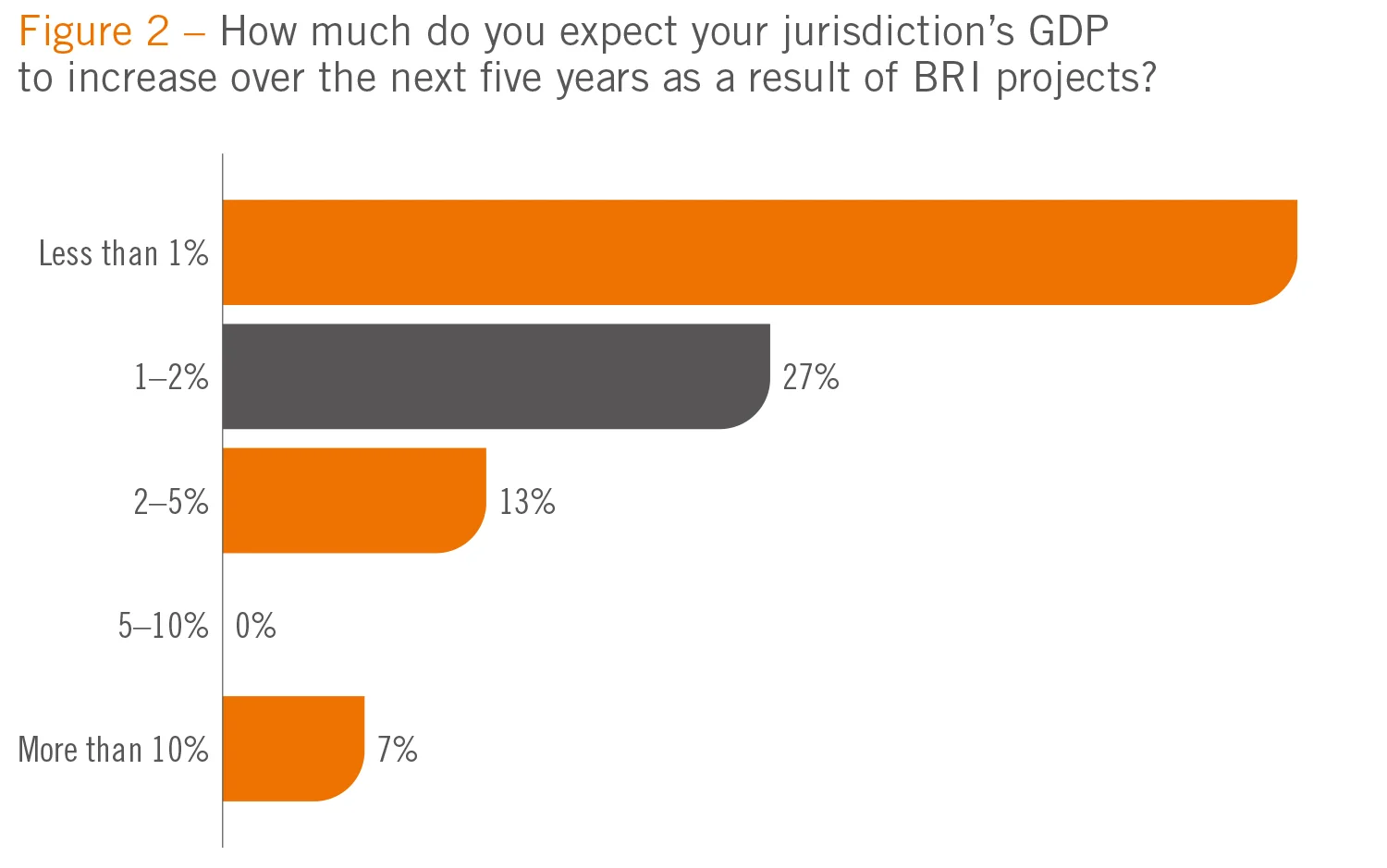

- 53% believe BRI projects will boost GDP by 0–1%, while 47% of respondents believe the boost will be even greater

- More than 90% believe the BRI will support other projects in their country

- Better co‑ordination is needed with national development strategies

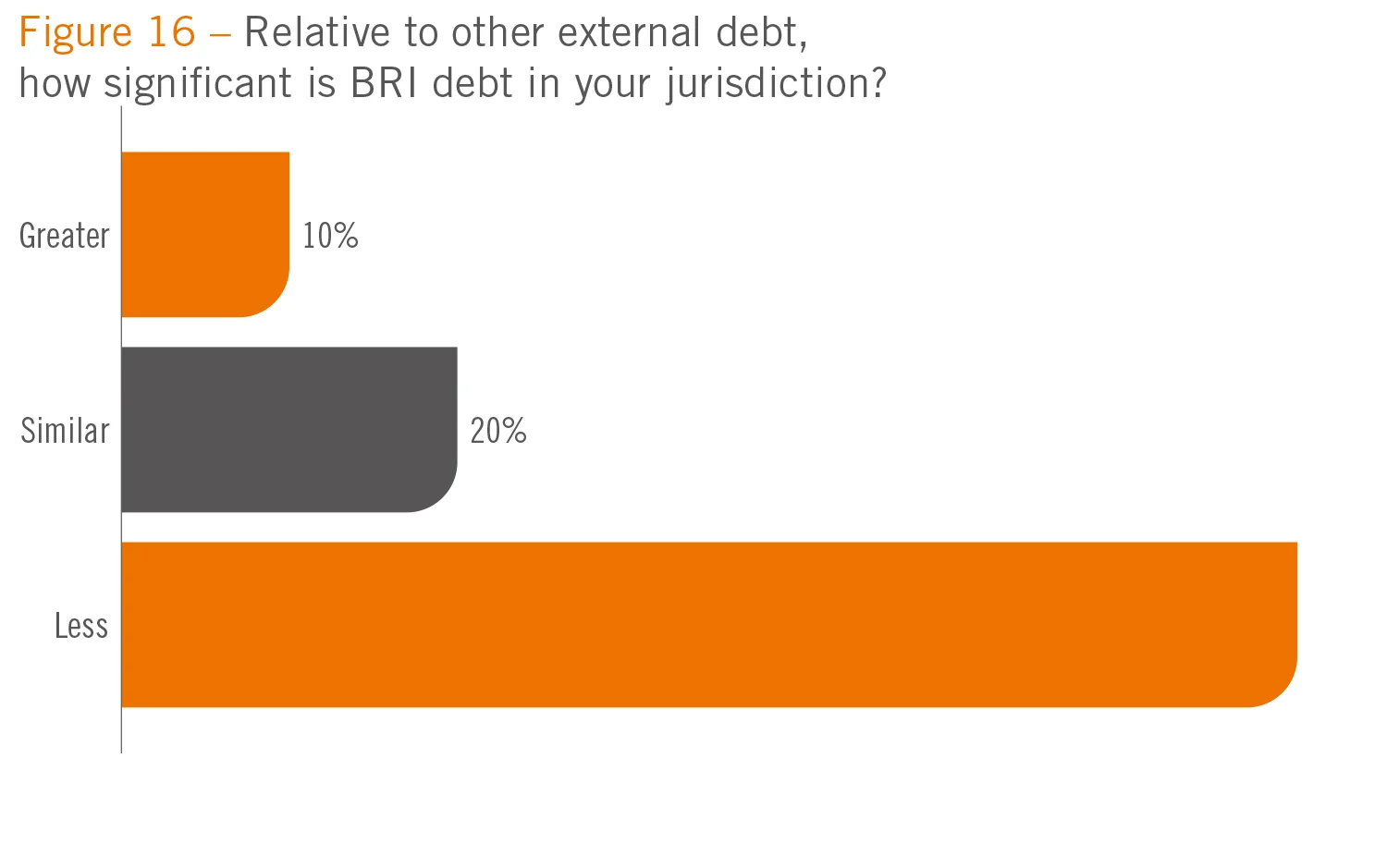

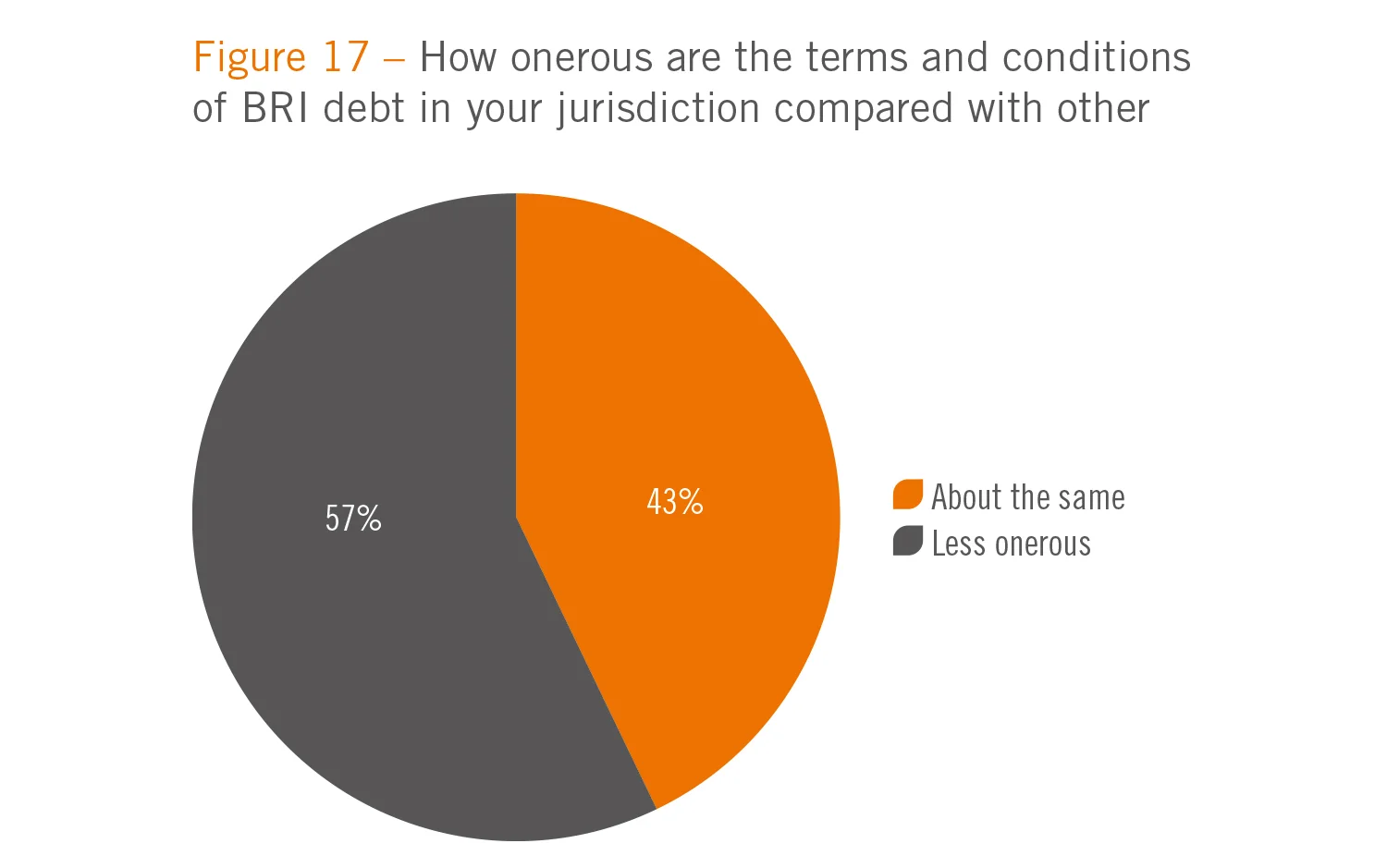

- BRI debt is smaller in scale and carries less onerous terms relative to other external debt

- All respondents consider their jurisdiction’s BRI debt to be sustainable

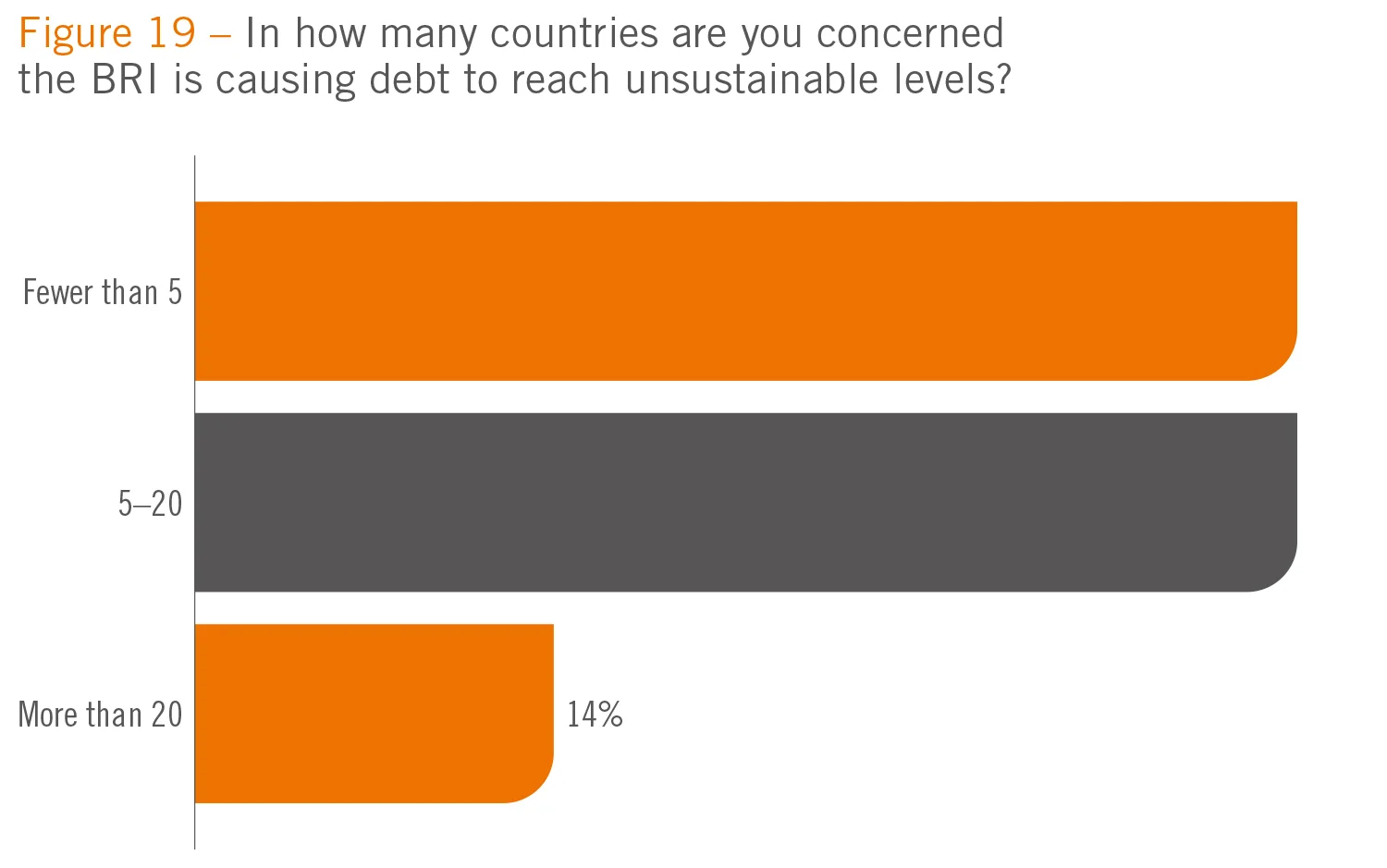

- There are concerns the BRI could cause debt to reach unsustainable levels in other countries

- Chinese development banks and multilateral institutions are expected to provide the most BRI funding

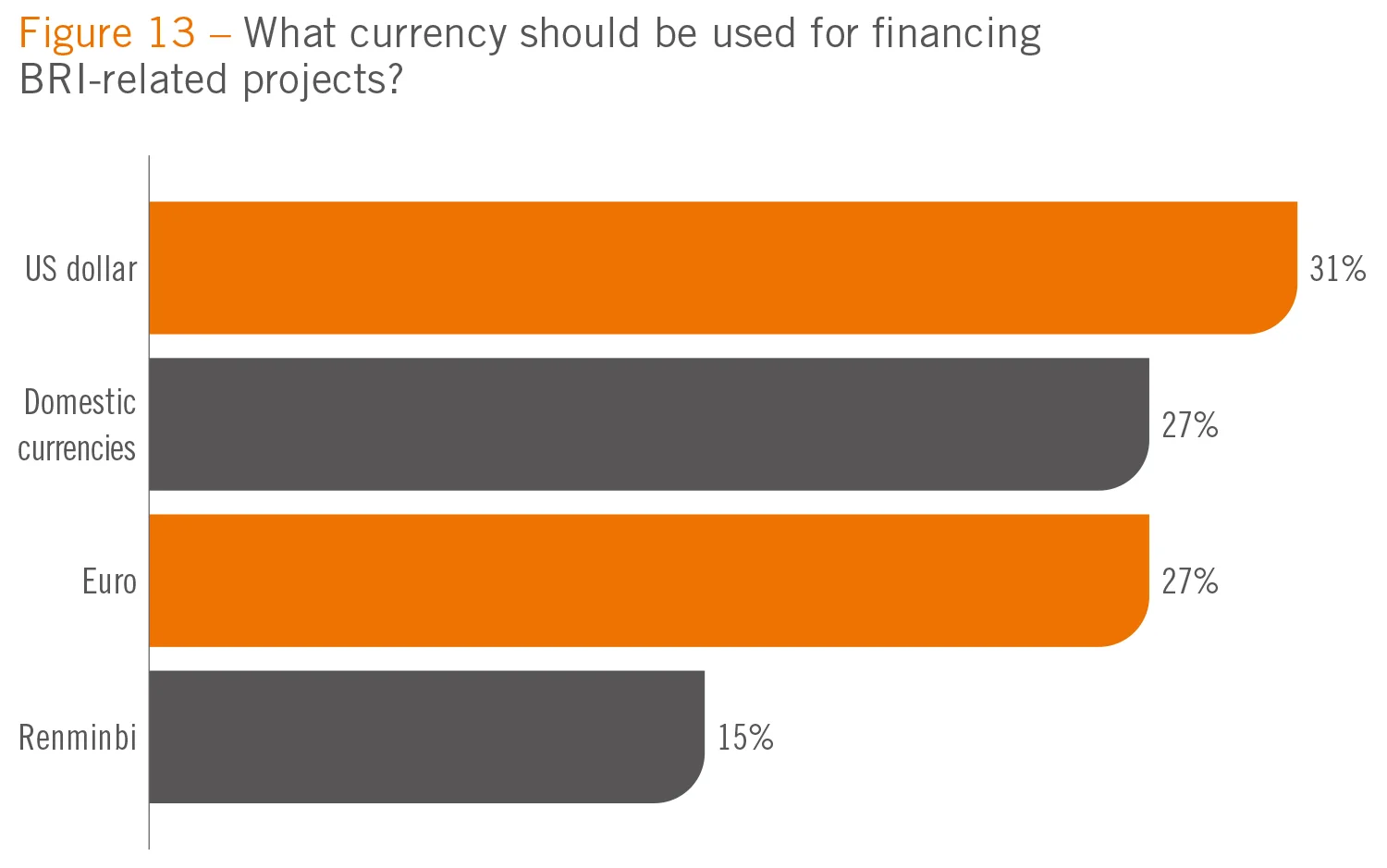

- The US dollar is the most advocated funding currency, followed by the euro and domestic currencies

- Renminbi funding is favoured by just 15% of respondents – 1% greater than the 2019 survey

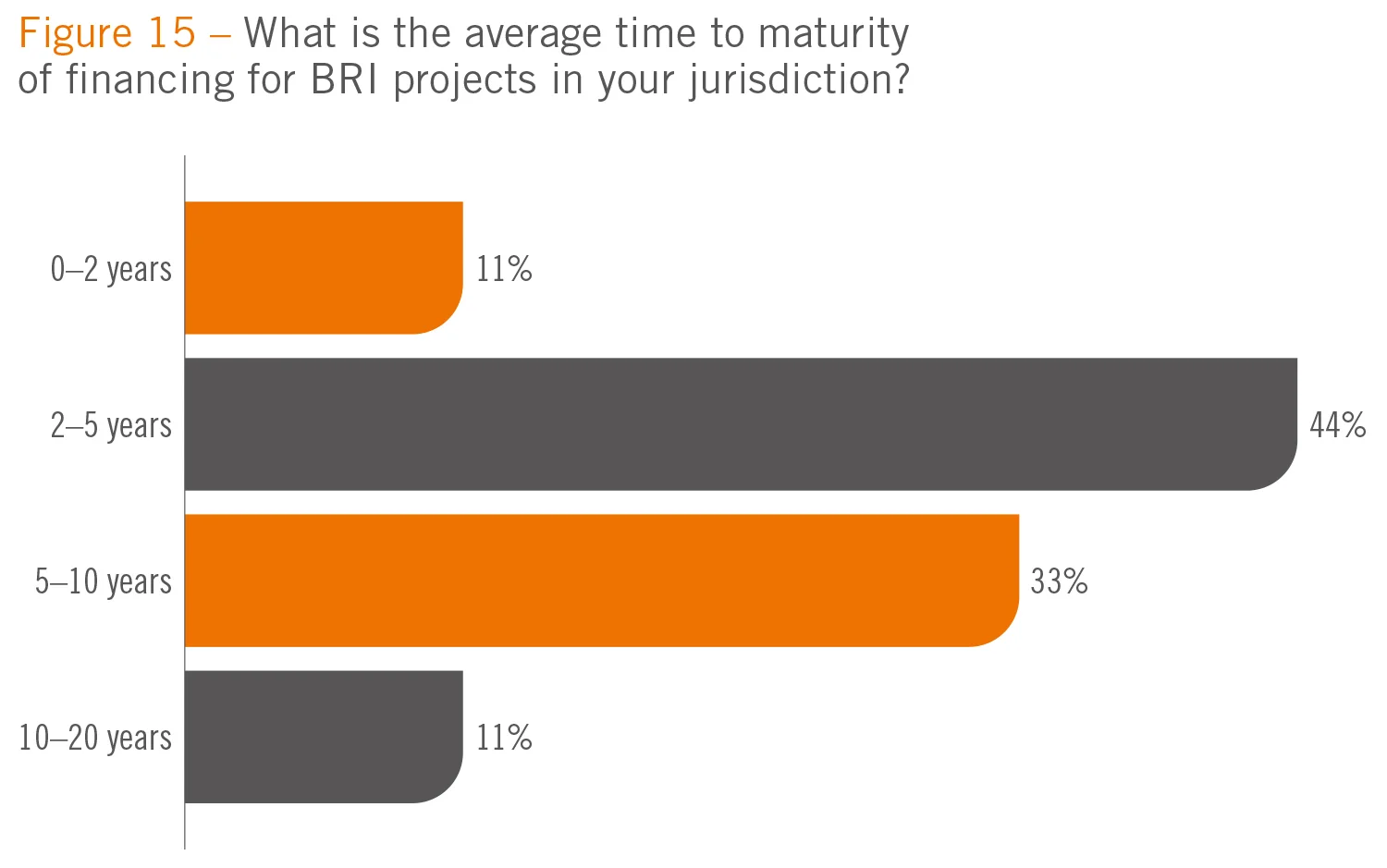

- BRI financing tends to mature sooner than five years

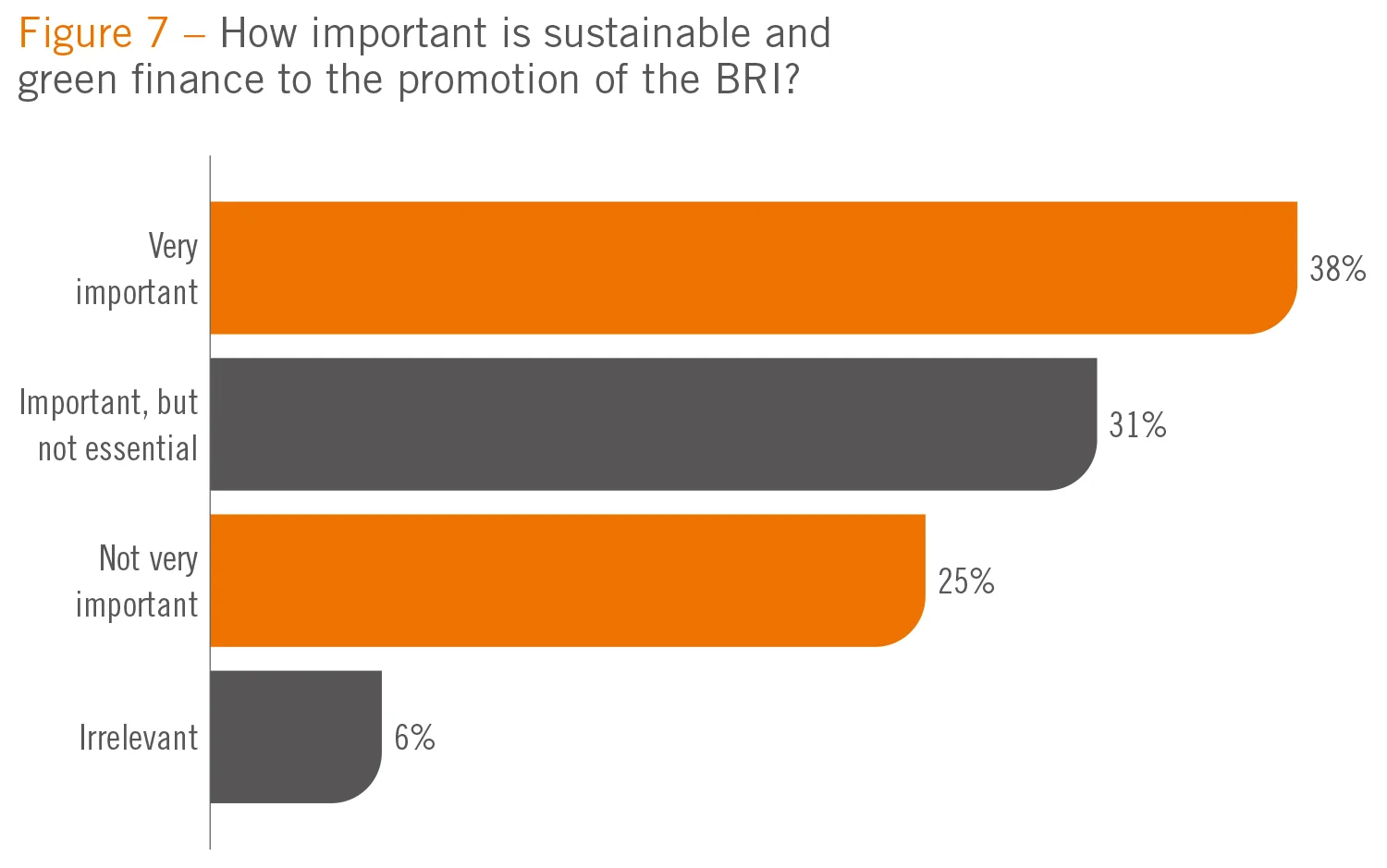

- More than 65% of respondents believe the BRI will be very important in promoting sustainable and green finance.

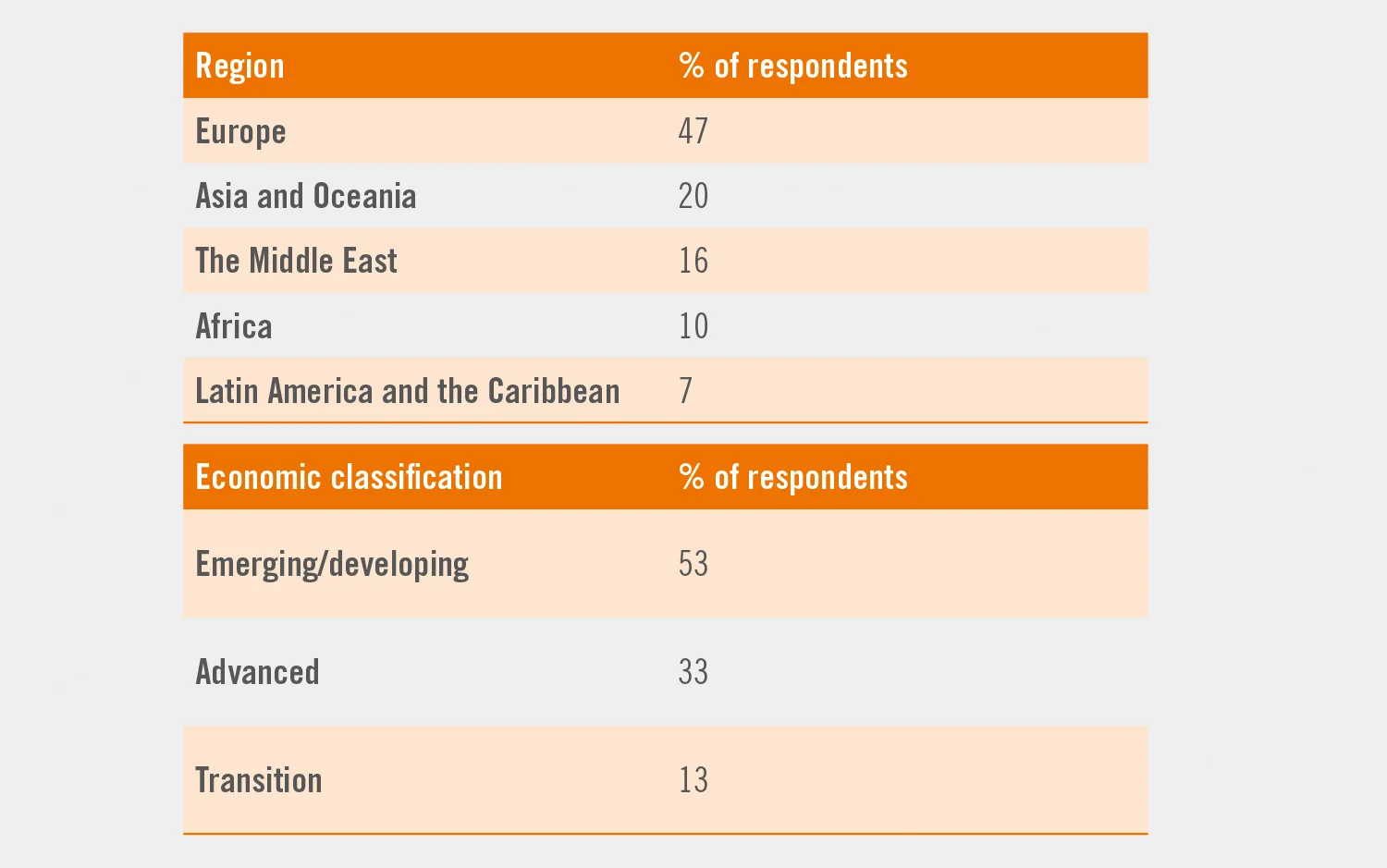

Profile of respondents

Central Banking received responses from 30 central banks participating in the Belt and Road Initiative. Almost half of the respondents were European, with central banks from the Middle East and Asia each making up 17%. In 2020, there was an increase in responses from central banks in Africa and the Caribbean, while the proportion of responses from the Oceanic region declined. More than 53% of responses to the 2020 survey came from emerging/developing countries, while 33% were from advanced economies and the remaining 13% from those in transition.

Percentages in some tables and graphs may not total 100 due to rounding.

Promoting growth and development

When established six years ago, the BRI’s core aim was to foster growth and development along the original Silk Route. The survey results reveal that all respondent central banks perceive the BRI as important for promoting global growth and development in the current international economic environment (see figure 1). This is largely in line with the position of supranational organisations, including the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development.

“The project will ease access to finance, trade and economic resources between different countries. Furthermore, it decreases the cost of transportation, increasing competition among producers and efficiency,” a central bank from the Middle East said. Similar views appear to be shared by jurisdictions outside the BRI’s traditional focus regions. “China has been assisting developing countries by providing loans at reasonable costs to develop their infrastructure and primary industries,” said a central bank from the Caribbean.

It was clear, however, that respondents were aware of the potential strategic risks associated with their jurisdictions’ involvement in BRI investments. While appreciating the opportunities for economic growth and development, a central bank from south-eastern Europe explicitly stated that: “The BRI should comply with economic principles and not discriminate against other projects.”

The BRI is expected to act as a catalyst to growth in participant countries, with four-fifths expecting a boost over the next five years of up to 2% (see figure 2). Half of respondents have relatively moderate expectations – indicating an expected increase of below 1% – while one-quarter expect an increase of 1%–2%. Responses were relatively consistent across jurisdictions regardless of the type of economy represented. There were also a few more optimistic responses. A central bank from South Asia indicated that the BRI-related increase to its GDP in the next five years could be 10% or greater.

Two central banks representing developing economies in the Middle East indicated an expected BRI-related increase to GDP of 2%–5% over the next five years. The Middle Eastern region not only is located at the crossroads of Europe, Africa and Asia – which the BRI aims to strategically connect – but also represents the hub of the ‘oil roads’ that feed China’s growing energy needs.

According to a report by the World Bank, countries along BRI corridors undertrade by 30%. Upgrading infrastructure, expanding trade and increasing investment would likely increase growth and income in most corridor economies. Real income gains could increase by up to 3.4%, according to the World Bank – but these gains would largely differ across countries. BRI transport projects could help lift 7.6 million people from extreme poverty (defined as earning below $1.90 per day) and 32 million people from moderate poverty (earning below $3.20 per day).

A breakdown in relations?

Trade tensions between China and the US have had a dampening effect on global growth over the past 18 months. As of February 7, 2020 the US had imposed tariffs on $550 billion worth of Chinese products. China, in turn, has set tariffs on $185 billion worth of US goods. While the impact of these protectionist policies has yet to fully materialise, the trade dispute appears to have had little impact on the BRI so far, according to those surveyed.

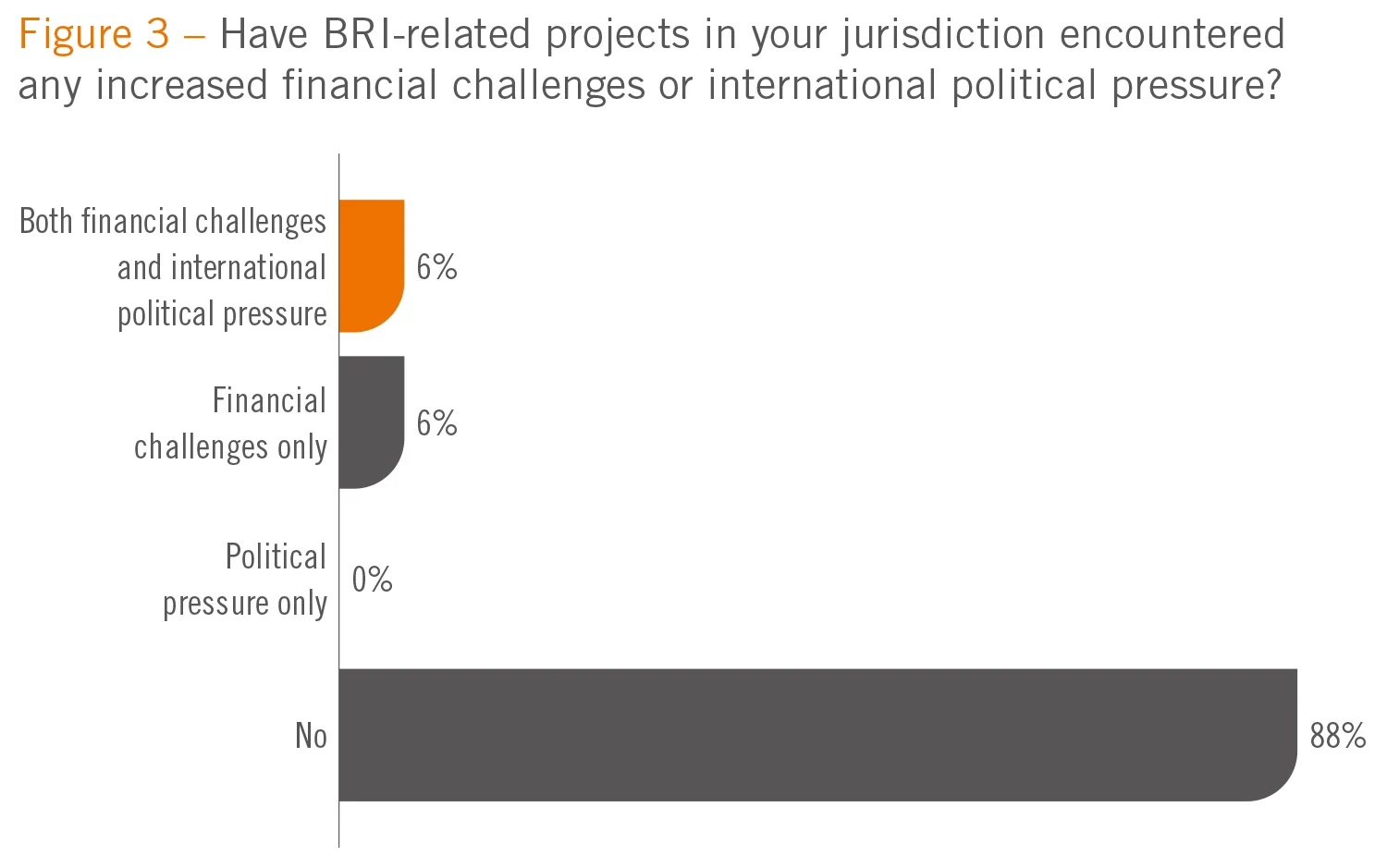

More than 85% of respondents indicated that implementation of BRI-related projects in their jurisdictions had not encountered any increased international political pressure or financial challenges due to trade frictions. A central bank from south-eastern Europe – one of the regions where the strategic interests of the US and China increasingly overlap – explicitly stated: “Trade tensions did not have a specific impact on the course of the projects financed through loans originating from China.”

However, respondents are aware of the potential fallout from the China–US trade dispute (see figure 3). This was particularly evident in Southeast Asia, where one central bank said that, while it was “not really affected”, the country is “prepared for any side effects of the China–US trade war”.

The results also indicated that some African and Middle Eastern countries could be caught in crosscurrents if trade relations weaken further. A respondent from an African central bank noted that China–US trade tensions were challenging BRI implementation on a financial level, while a respondent from the Middle East said BRI projects were facing both political pressure and economic challenges. Both of these central banks are in regions whose growth is, to a large extent, dependent on foreign investment. As a result, they are often more vulnerable to the political and financial consequences of international tensions – particularly when it involves the world’s two largest economies.

Project evolution

In parallel to a shifting political and economic climate, the scale and scope of BRI projects has also evolved. Many early BRI projects focused on energy creation and infrastructure – particularly related to transportation. This is a continuing theme. In April 2019, China and Kenya agreed to build two projects with a total value of $2.23 billion: the Konza Data Centre and Smart Cities deal was valued at $1.72 billion, while the Jomo Kenyatta International Airport–Westlands Highway project is to be built at a cost of between $510 million and $650 million, 80 kilometres south of Nairobi.

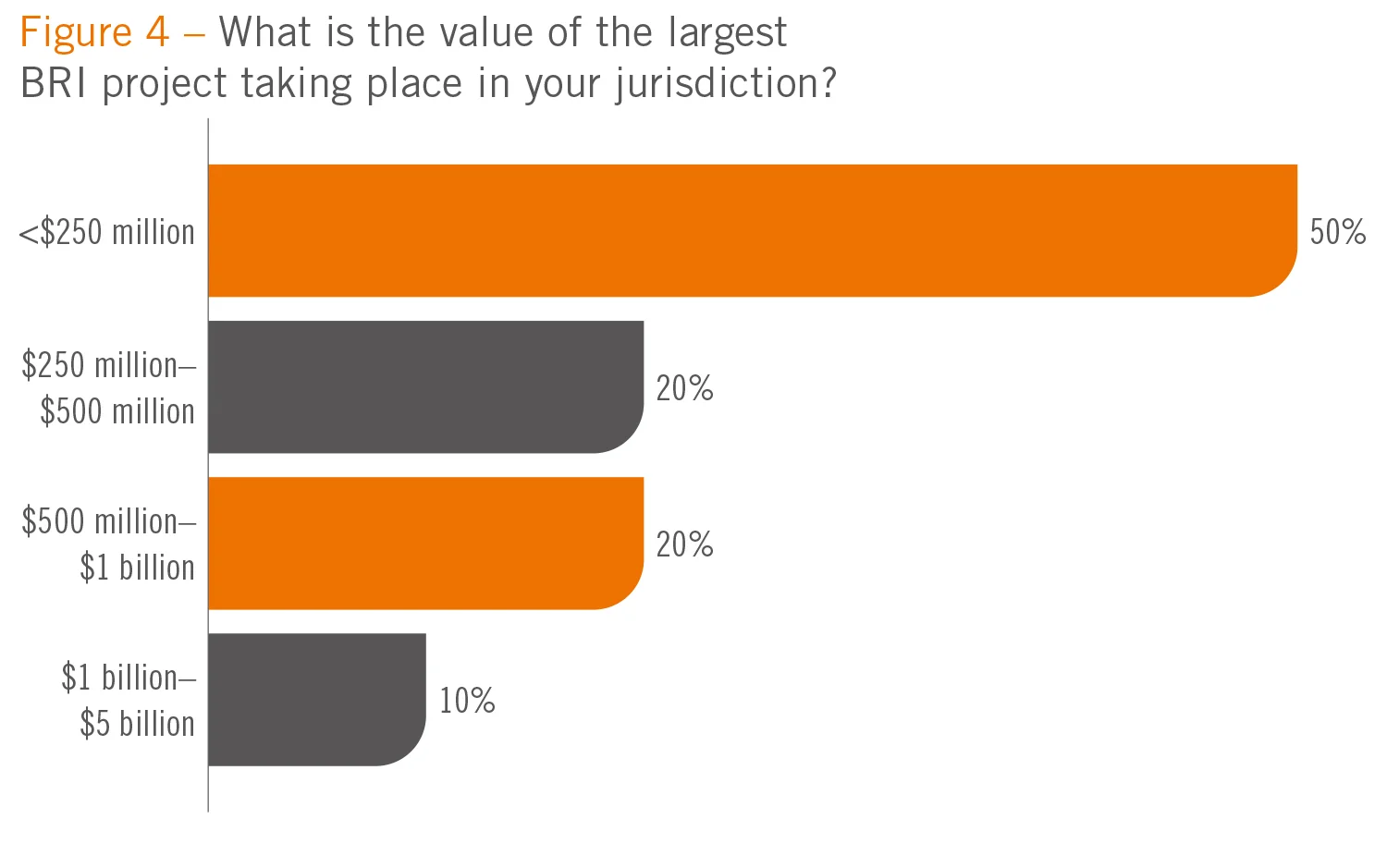

There are plenty of smaller transactions too. Of those surveyed, 90% indicated the size of the largest BRI project taking place in their jurisdictions was valued at less than $1 billion – with half of respondents highlighting that combined investments into a single BRI project do not exceed $250 million in total.

This suggests the BRI does not focus solely on the mega infrastructure projects it is traditionally associated with, but also involves local investments of a relatively smaller size.

Twenty per cent of respondents indicated that the combined investment value of the single largest BRI project in their jurisdiction is between $500 million and $1 billion (see figure 4). These respondents heralded from central and Eastern Europe, which confirms the strategic importance of the region for China and indicates the BRI’s potentially significant role in future China–European Union relations. Additionally, the survey results revealed that, in 20% of respondent jurisdictions, the value of the largest BRI project falls within the range of $250–$500 million; while 10% of central banks indicated the size of their jurisdictions’ largest BRI project as above $1 billion.

Acording to data from Refinitiv, Sri Lanka has emerged as the country with the highest number of BRI projects announced as of July 2019, with seven developments with a combined value of nearly $700 million. While Pakistan has attracted plenty of attention for its involvement in BRI projects, Russia has received the largest investment from China – $298 billion worth of projects are currently under way, according to Refinitiv.

Specific BRI-related projects include Moscow’s Metro Line 3 – the first metro project undertaken by Chinese enterprises in Moscow. The building of the 4.6km metro network began in 2017 and will be completed by the end of 2020. Another deal was signed during the second Belt and Road Forum in Beijing in April 2019: China National Offshore Oil and China National Oil and Gas Development acquired a combined 20% of Novatek’s Arctic Liquefied Natural Gas 2 project in northern Russia.

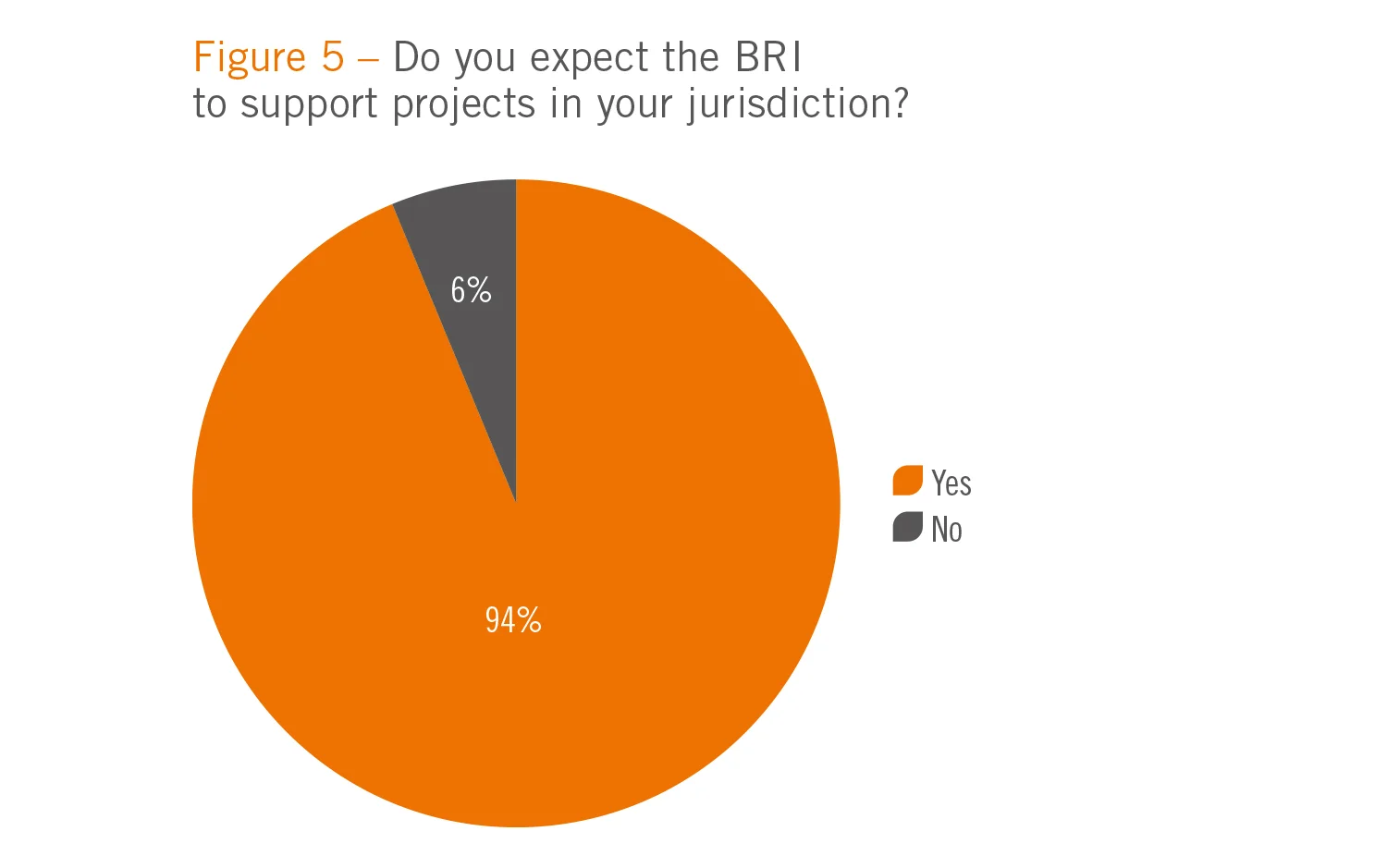

Meanwhile, more than 90% of respondent central banks expressed an expectation that the BRI would support projects in their jurisdictions (see figure 5). A central bank from the Caribbean region added: “The support is evident via continued road infrastructural expansion, primary industries and public buildings.”

Some qualitative responses also focused on the spillover effects of BRI investments. A respondent from a Southeast Asian emerging market economy stated that the BRI is expected to support projects indirectly as it “will help with job creation and subcontract business activities”. A Middle Eastern central bank in a developing economy suggested the impact of BRI investments will materialise “through increasing and easing trade and mobility between countries”.

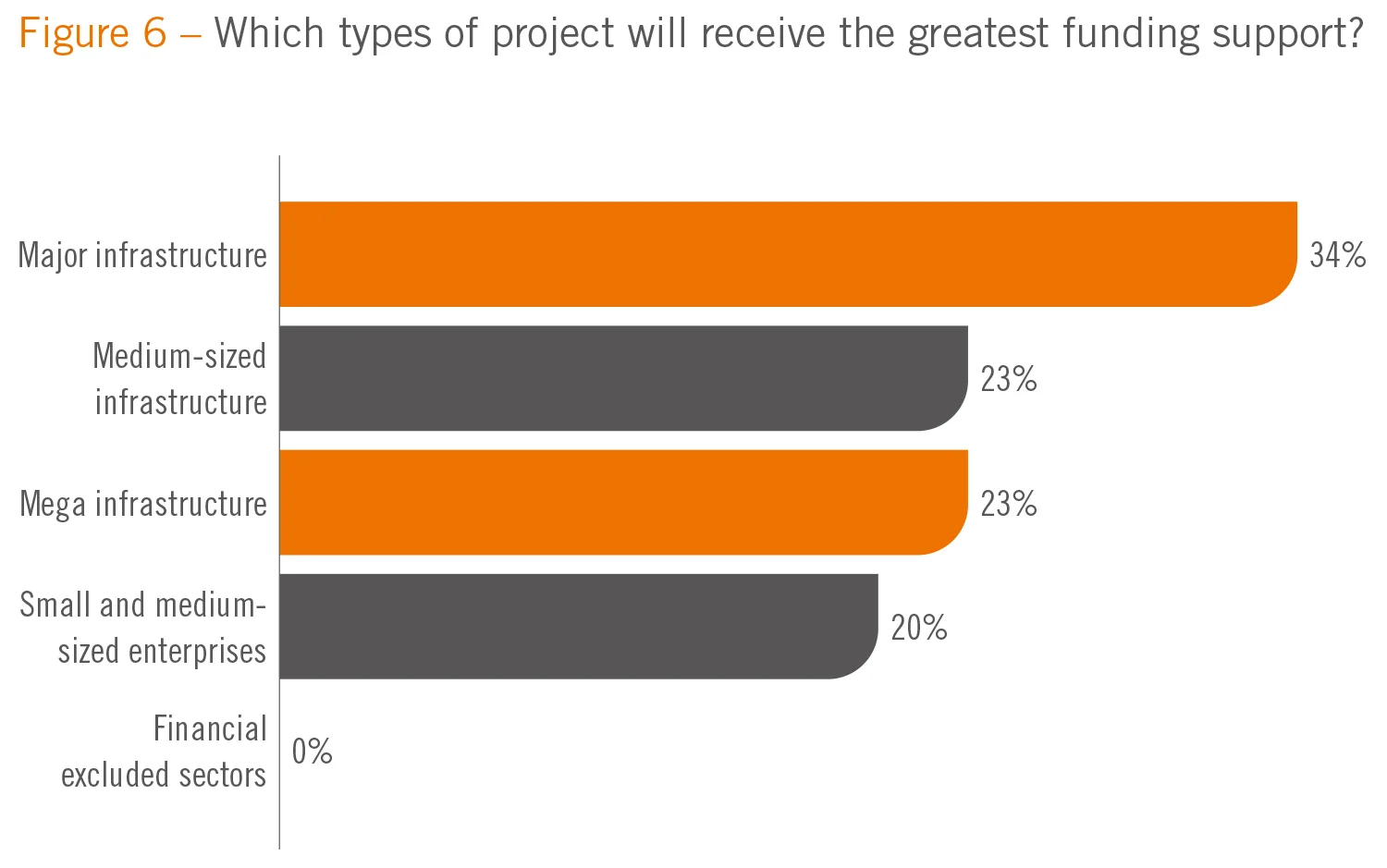

Regarding the taxonomy of projects expected to receive the greatest funding support, respondent central banks expect the BRI to simultaneously target projects of different sizes and scope across a range of jurisdictions. However, the results revealed major infrastructure projects represent the most significant focus of BRI investments, featuring in 34% of responses (see figure 6). Mega and medium-sized infrastructure projects featured in almost a one-quarter of responses each – with small and medium-sized enterprises selected in one-fifth of participating central banks’ responses. None of the respondents indicated BRI support for financially excluded sectors.

Environmental and technological impact

At the second Belt and Road Forum, President Xi signalled the environment as one of the key pillars underpinning the success of the BRI moving forward. The BRI, at its core, is probably the most ambitious infrastructure project in history. However, building the land-based Silk Road Economic Belt and the Maritime Silk Road will require massive amounts of concrete, steel and chemicals, creating new power stations, mines, roads, railways, airports and container ports – often in countries with poor environmental oversight.

Since 2000, Chinese banks have invested $160 billion in international energy projects, almost as much as the World Bank and regional development banks. But, unlike the World Bank, 80% of China’s overseas energy investments went to fossil fuels compared with just 3% to solar and wind, and 17% to hydro projects.

While China has imposed a cap on coal consumption at home, its activities abroad appear to have grown. Chinese companies are involved in around 240 coal projects in numerous BRI member countries, including in Bangladesh, Pakistan, Serbia, Kenya, Ghana, Malawi and Zimbabwe. China is also financing about half of proposed new coal capacity in Egypt, Tanzania and Zambia.

However, just over two-thirds of respondents believe sustainable and green finance will be important to the promotion of the BRI (see figure 7). Thirty-eight per cent said it was very important, with a further 31% reporting it as important but not essential. One-quarter said it was not important. More effort may be required to reinforce President Xi’s vision of a “green, healthy, intelligent and peaceful” BRI. While the Chinese government has released guidelines such as the Green investment principles for the Belt and Road, which parallel domestic green finance guidelines. At present, they are non-binding.

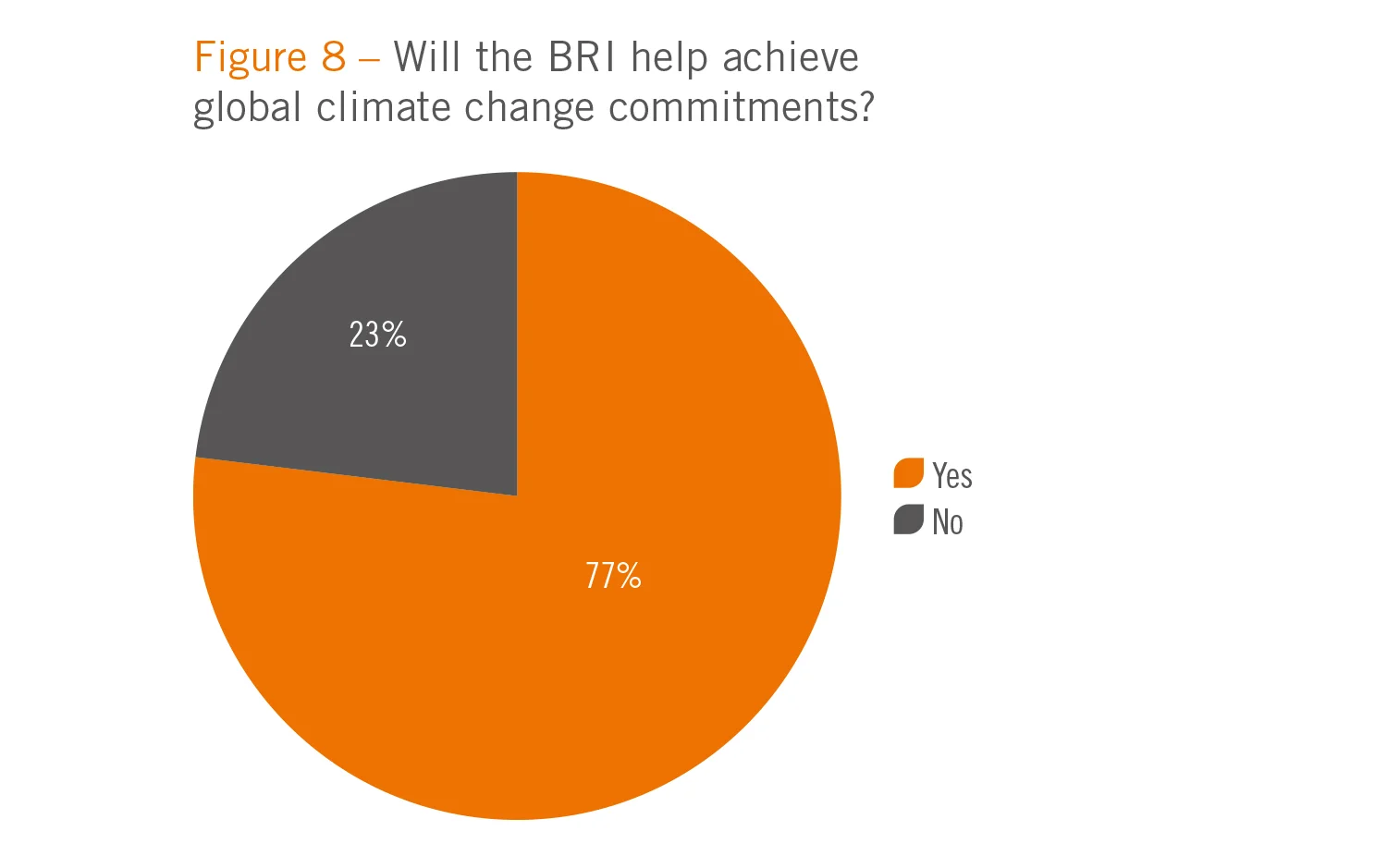

While 77% of respondents said the BRI would help achieve global climate commitments, 23% did not (see figure 8). “The project will require a huge investment in infrastructure and other economic projects, which in turn is expected to lead to more climate changes,” said a small central bank from the Middle East.

The BRI, however, looks well positioned to help improve the technological capacity of its member countries. At the second Belt and Road Forum, President Xi said: “Innovation produces productivity, which makes companies competitive and countries strong.” Under the BRI, China has committed to pursuing four major technological initiatives: scientific exchanges, joint research labs, technological parks co‑operation and general technological transformation.

The number of technological projects initiated under the BRI has been limited in comparison to energy infrastructure. Around $17 billion has been allocated for projects including fibre-optic cable and telecommunications networks, e-commerce and mobile payments, smart city-related initiatives and data centres. India’s telecoms operator Bharti Airtel received $2.5 billion and Russia’s Rostelecom $600 million, in part to purchase Huawei and ZTE equipment. Alibaba, meanwhile, invested $4 billion in online marketplace Lazada, and Ant Financial’s Alipay has rolled out in eight countries.

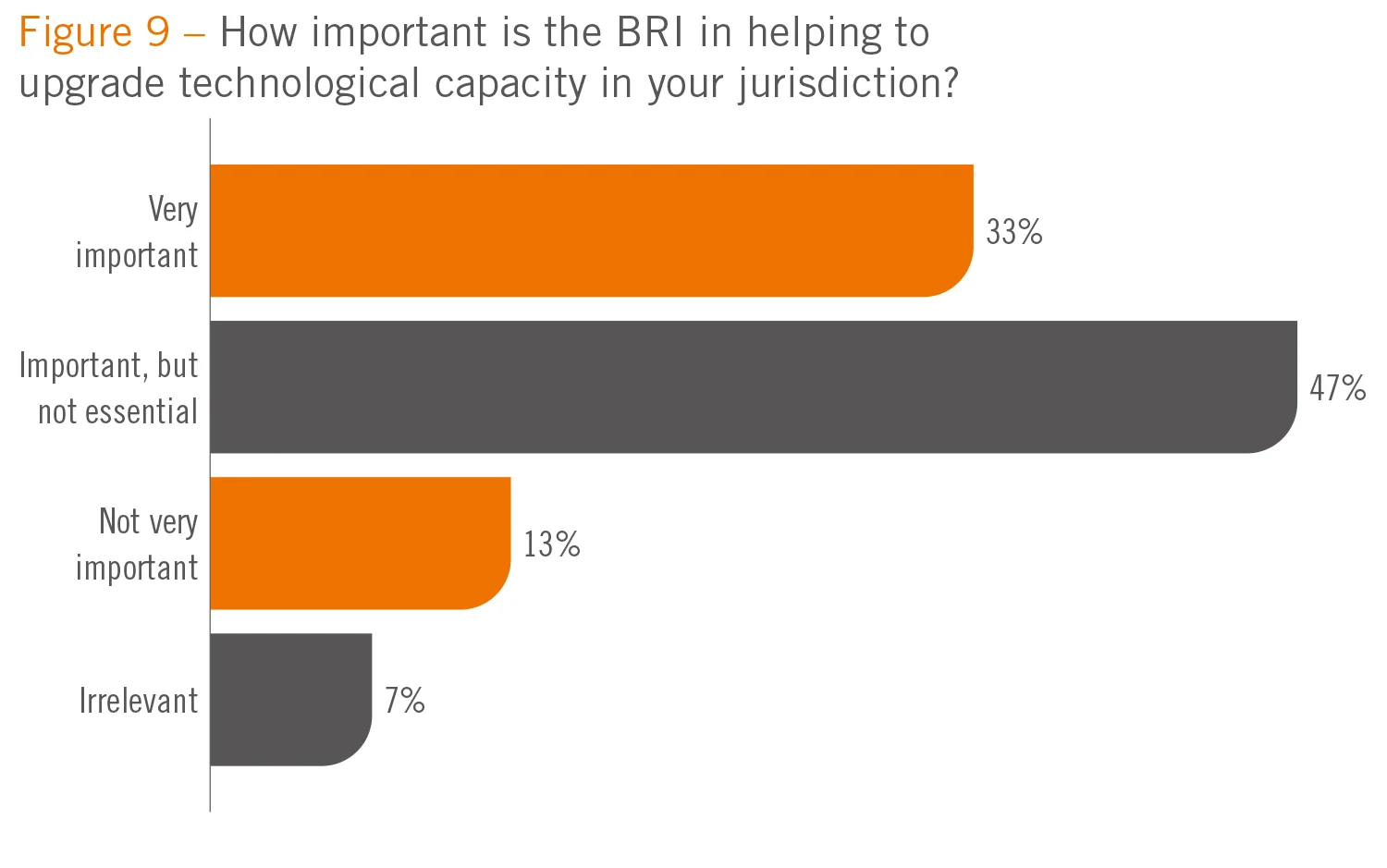

Respondents largely agreed that the BRI would be crucial to the development of technology in their region – 33% said it would be very important while 47% said it was important but not essential (see figure 9).

For countries that rank low in the Global competitiveness report for technology output, the BRI could be a game-changer. “The BRI could help – especially in having locals working alongside the Chinese,” a Caribbean central bank said. “There should be a standard programme for the transfer of knowledge by training locals here and in the source country.”

One of the biggest industrial park initiatives is in Belarus, where China has helped established an almost 100 square kilometre park outside the city of Minsk. At the end of February 2019, 43 companies registered at the park – 26 were from China, 10 from Belarus and seven from other countries, including the US and Russia. Such efforts are far from universal, however. A respondent from a small central bank from Eastern Europe said: “At the current juncture, the presence is limited to road infrastructure, and hence has had no major impact on technological capacity.”

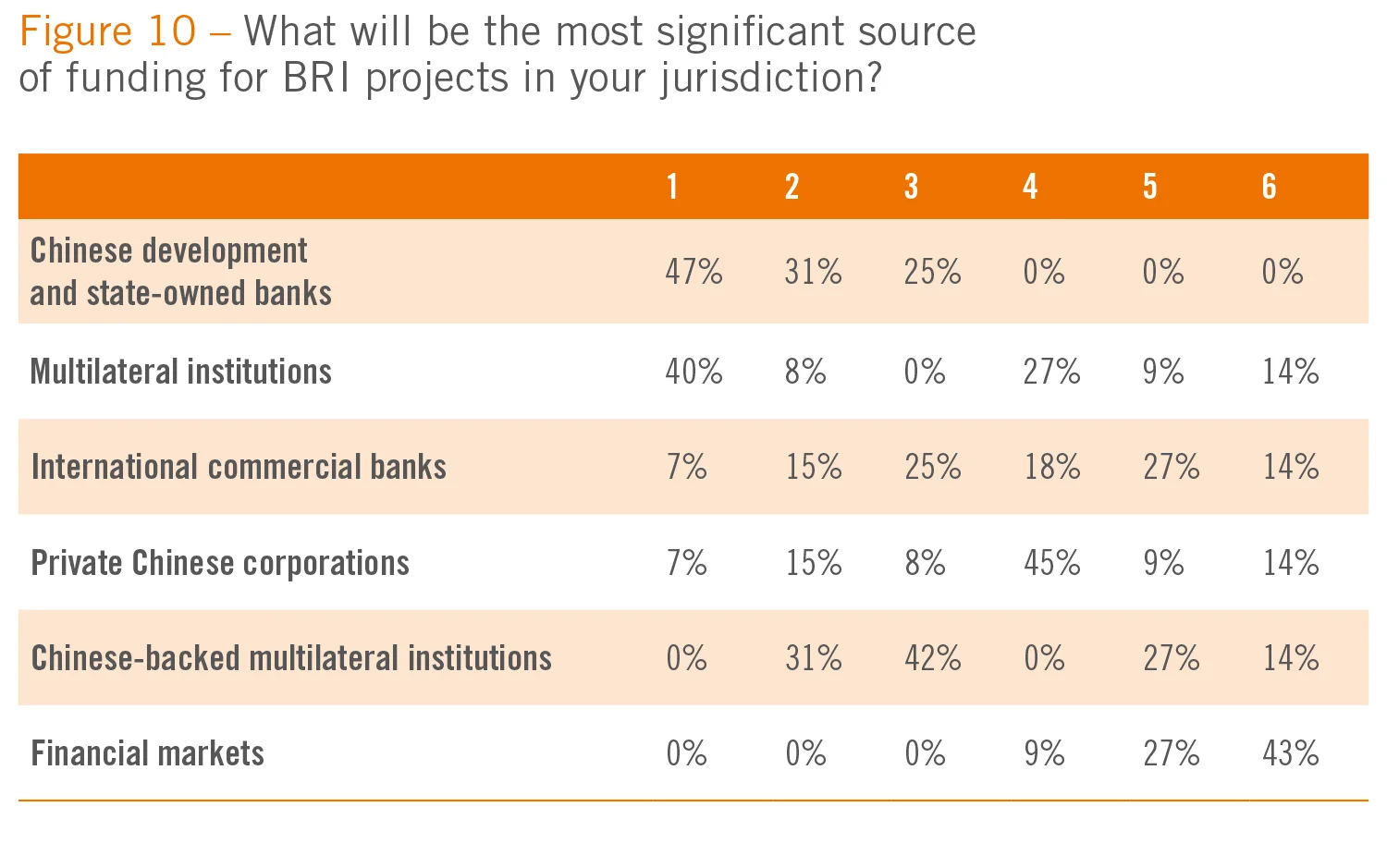

Preferred sources of funding

Currently, a large proportion of BRI financing comes from China. Responses from member countries corroborate this dynamic: 47% of respondents said they expected the majority of BRI funding to come from Chinese development and state-owned banks, with Chinese-backed multilateral institutions and private Chinese corporations also seen as core sources of funding (see figure 10).

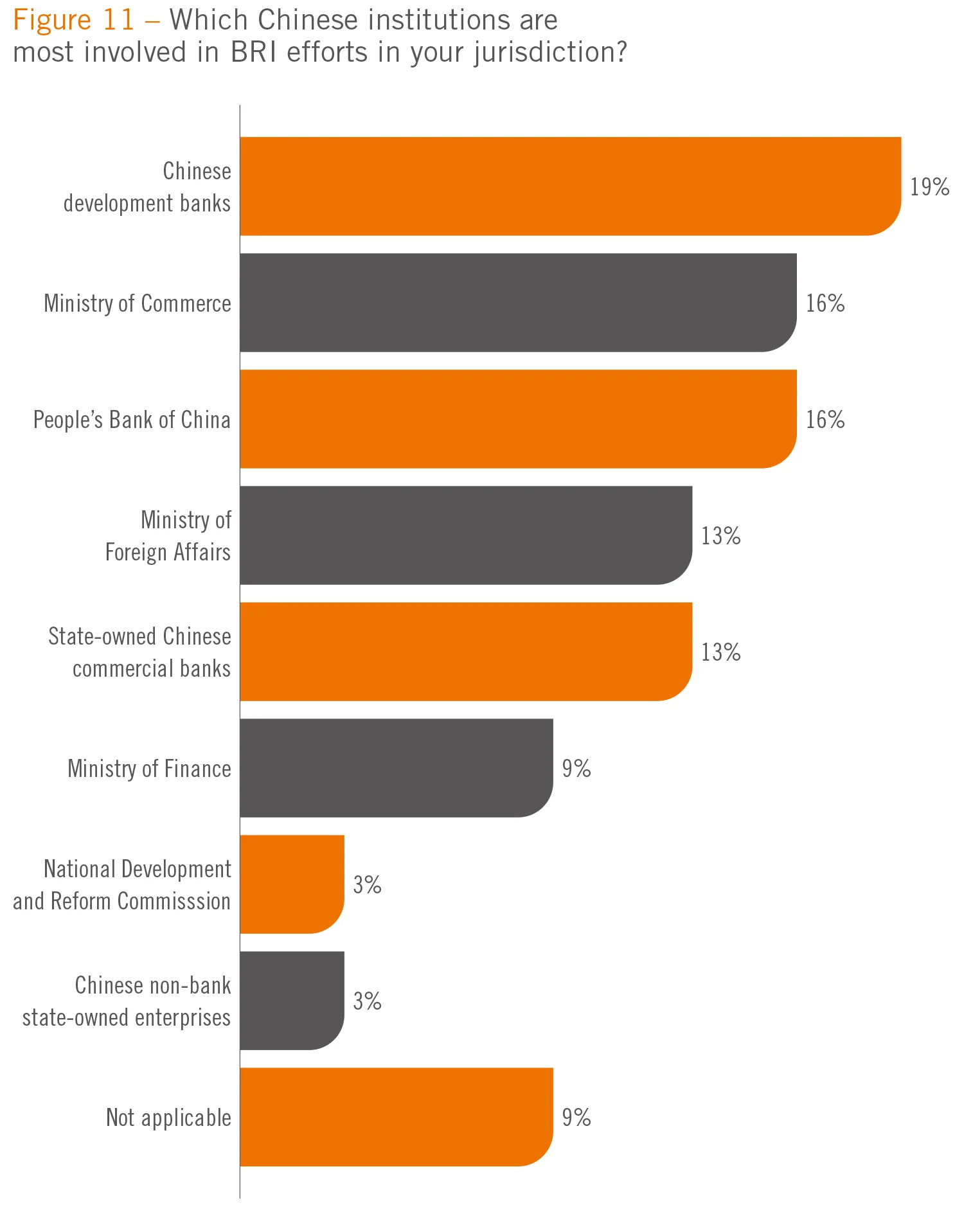

Chinese development banks are the most involved in BRI projects from the perspective of survey respondents, with the China Development Bank (CDB) and the Export-Import Bank of China singled out by a number of them as providing core funding for projects. Both lenders operate directly under the State Council of the People’s Republic of China, and are responsible for raising funds for and implementing economic policies of the government at home and abroad. Their BRI investments total hundreds of billions of dollars, with the CDB committing more than $200 billion.

The CDB – which specifically finances infrastructure, energy and transportation projects – is one of the largest financial backers. As a result, the institution is an important driver behind the BRI and its contribution is consistently growing. It is also the largest foreign-currency lender, and the second-biggest bond issuer in China.

A shared feature of the other Chinese institutions that feature prominently in the responses of the participating central banks – the Ministry of Commerce (16%), the People’s Bank of China (16%), Ministry of Foreign Affairs (13%) and state-owned commercial banks (13%) – is that these institutions are also either part of, or come under the direct jurisdiction of, the central government (see figure 11). These figures largely confirm the strategic position of the BRI in the context of China’s foreign policy efforts; and, to some extent, also highlight the additional, political dimension of the individual BRI projects and investments.

However, with the total trade volume between China and participating countries surpassing $6 trillion in 2019 and a need for an additional $26 trillion in investments by 2030 to keep the economy growing, significant additional sources of funding will be crucial to ensure the continued success of the initiative.

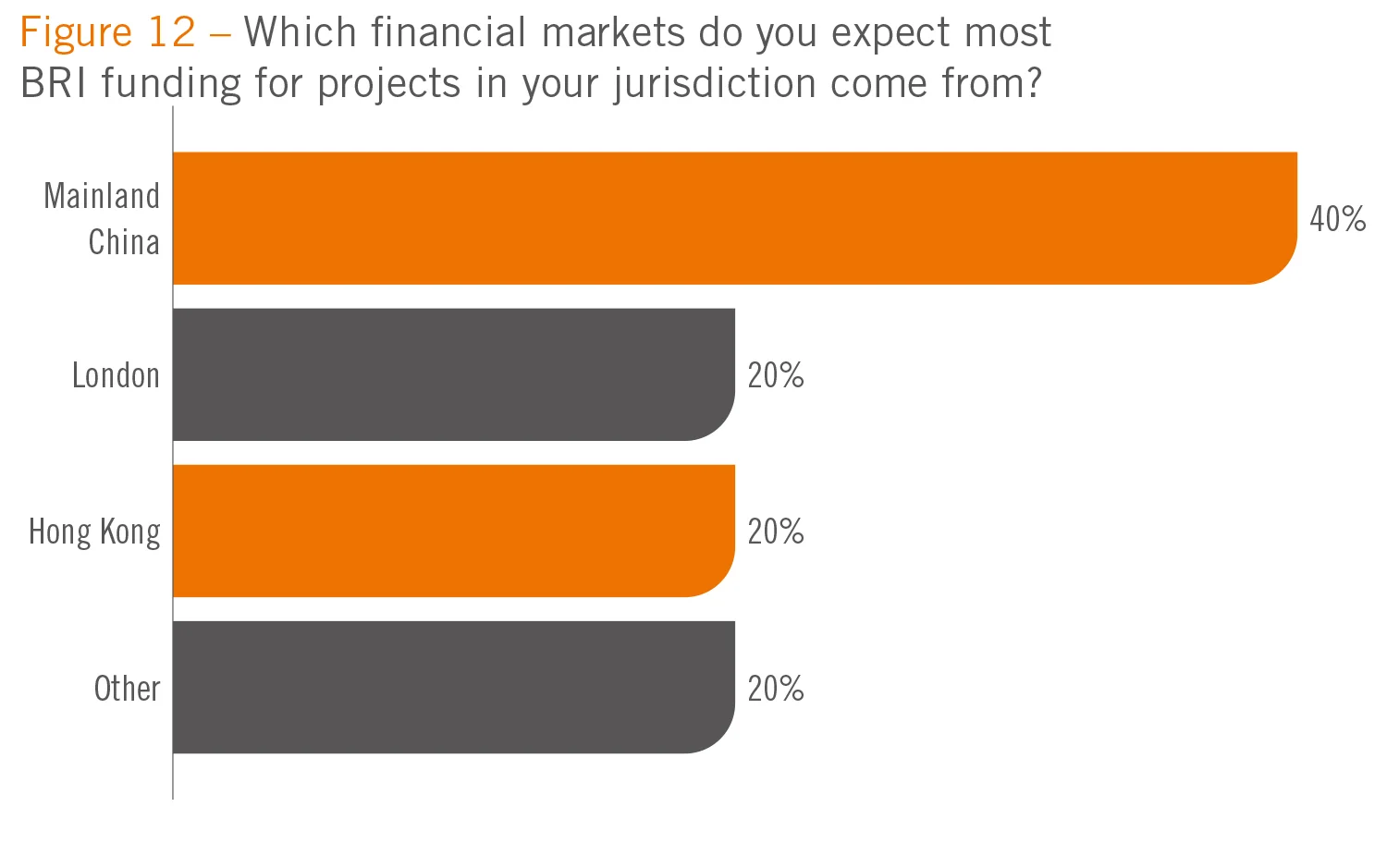

A small proportion of respondents now expect funding for BRI projects to come from financial markets. Markets in London, Hong Kong and mainland China were all mentioned by respondents as possible sources of funding (see figure 12). The London Stock Exchange (LSE), for example, supports the BRI through a variety of services and initiatives. At the end of 2019, it facilitated $80 billion to be raised in equity capital and $170 billion in debt capital. It also claims to provide a “world-class listing infrastructure” for the BRI. Kazakhstan, one of the countries along the BRI, has listed 12 companies on LSE, with $14.4 billion in total market capitalisation. More than 100 renminbi-denominated bonds are currently listed on the exchange. It also supports Chinese firms issuing bonds denominated in other currencies. The Bank of China, through its Hungarian branch, for example, listed its first euro-denominated bond on LSE to fund BRI projects.

While 40% of respondents that specified markets as a source of funding named China as the destination of choice, renminbi usage remains limited (see figure 13). A total of 15% of respondents said they would advocate using the Chinese currency for financing BRI-related projects. Despite US–China trade tensions, the US dollar remains the currency of choice (31%), followed by the euro (27%) and domestic currencies (27%).

In recent years, Chinese officials have made a concerted effort to facilitate the renminbi’s international use. Since 2009, the People’s Bank of China has signed more than 30 bilateral currency swap agreements with a range of central banks in countries ranging from Argentina to Nigeria. Meanwhile, the IMF officially inducted the renminbi into its elite club of global reserve currencies in 2016.

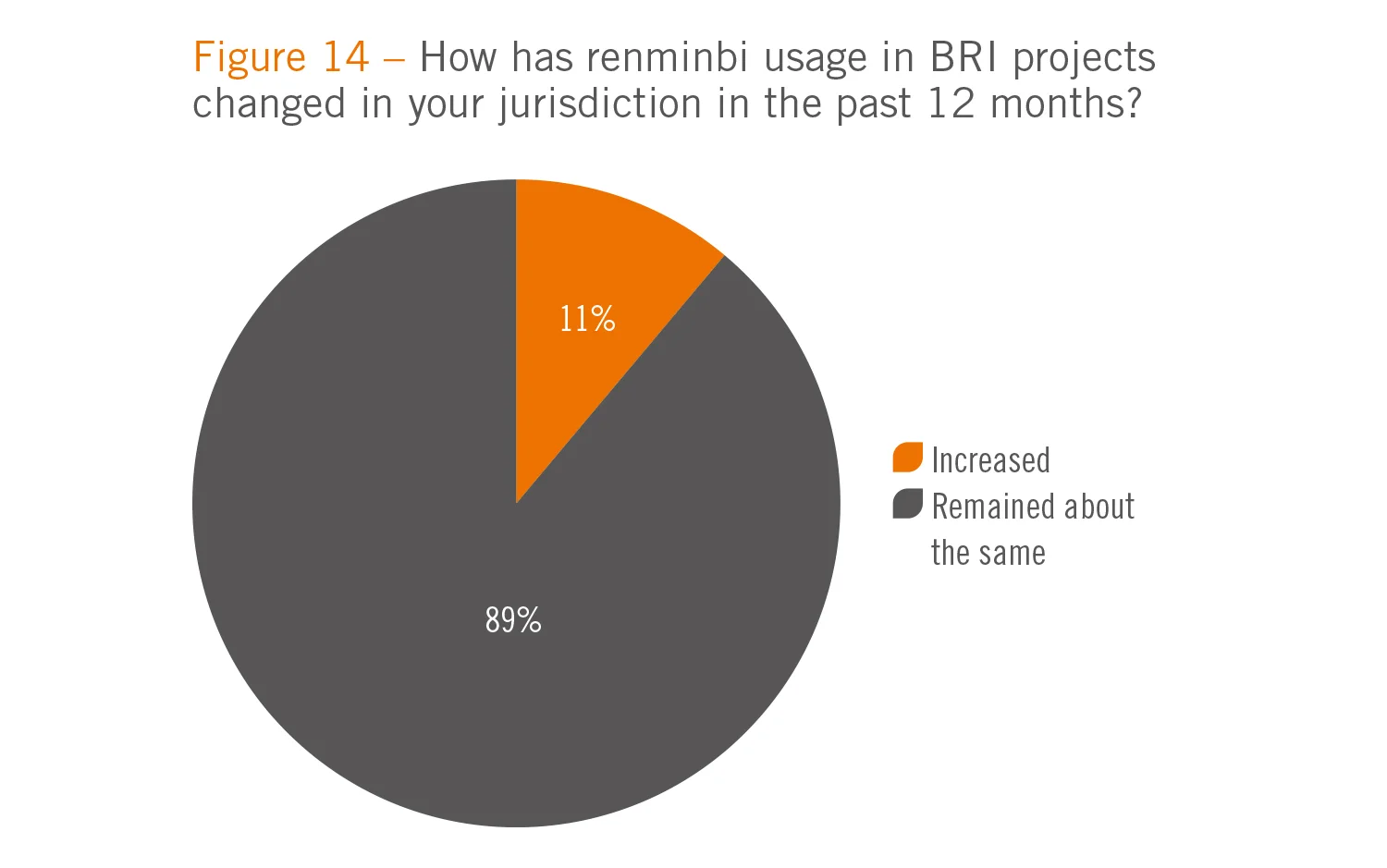

Despite these developments, almost 90% of respondents said the use of renminbi in BRI projects had not changed in the past 12 months (see figure 14). There are even signs that international renminbi use may have declined. In August 2015, the renminbi stood as the world’s fifth most active currency for domestic and international payments, with a 2.8% share according to Swift. By January 2020, it had slipped to sixth, with a share of 1.94%. The US dollar, however, has maintained its leading share of domestic and international payments at roughly 40%.

Debt sustainability

The average time to maturity of financing for BRI projects varied among respondents: 55% said less than five years, 33% between five and 10 years, and 11% said between 10 and 20 years (see figure 15).

Currently, there appears to be only been one instance of China taking control of a BRI asset – it now operates Hambantota Port in Sri Lanka on a 99‑year lease.

The Center for Global Development says another seven BRI recipient countries – Djibouti, Kyrgyzstan, Laos, the Maldives, Mongolia, Montenegro and Tajikistan – are potentially in BRI- related debt distress. But Sri Lanka is not the only country showing signs of struggling with BRI-related debt. Some believe Pakistan’s previous government overcommitted on its $62 billion China–Pakistan Economic Corridor, which resulted in the need for an austerity budget and an IMF bail-out – although Pakistan officials stress that Chinese support has already contributed to the introduction of vital infrastructure that will promote its future tax revenue growth.

Respondents to the survey tend to view BRI debt as less significant in scale than other forms of external debt (see figure 16). Only 10% said it was greater in scale, while 20% said it was the same. A lot of external funding comes from sources other than China. “Most of the loans are from the international capital market and international financial institutions such as the IMF, International Development Bank and World Bank,” said a small central bank from the Caribbean region.

A central bank in Eastern Europe said the reason for the smaller proportion of Chinese debt was because of the smaller scale of the projects involved. “The BRI is limited only to two highway projects in our nation, and so the debt obligations are smaller,” it said.

BRI debt is generally perceived not to carry onerous terms and conditions (see figure 17). Almost 60% of respondents said BRI debt had more manageable terms relative to other external debt.

One central bank in the Caribbean region said debt sustainability was not a significant issue for their nation due to changes to its own fiscal policies. “We are in a position where we can easily manage BRI loans due to prudent fiscal policies,” it said.

At the Belt and Road Forum, President Xi made explicit China’s commitment to supporting global debt goals and environmental sustainability. Christine Lagarde, at the time managing director of the IMF, responded positively: “I have said before that, to be fully successful, the BRI should only go where it is needed. I would add today that it should only go where it is sustainable in all aspects,” she said. “Fortunately, the Chinese government is already taking some steps to ensure this is the case. The new debt sustainability framework that will be utilised to evaluate BRI projects is a significant move in the right direction.”

The changes could be having the desired effect. All survey respondents said they would categorise BRI-related debt as sustainable in their jurisdictions (see figure 18). However, they did exhibit some fears about debt levels in other BRI states. Fifty-seven per cent of respondents said they were concerned the BRI was causing debt to reach unsustainable levels in five or more countries, with 14% saying they were concerned about debt levels in 20 or more countries (see figure 19).

President Xi and other Chinese officials have repeatedly said they do not want debtor nations to be in difficulty. China and 27 other countries have jointly adopted the Guiding principles on financing the development of the Belt and Road, which highlights the need to ensure debt sustainability in project financing. To assist nations in avoiding excessive debt, new institutions have also been created. The China‑IMF Capacity Development Center is being funded by China, as is the International Development Cooperation Agency.

Room for improvement

During the six years the BRI has been in operation, much practical progress has been made. Many projects concerning transport construction and industrial infrastructure have already started to benefit member countries. In Africa, Chinese investment has seen the development of the first electrified railway line in East Africa between Ethiopia and Djibouti. More than 750km long and with an operating speed of 120km per hour, the Addis Ababa–Djibouti Railway has reduced travel time from the Port of Djibouti to the Ethiopian capital to less than 12 hours. The journey previously took three days.

However, some respondents reported that BRI project plans need to be better co‑ordinated and aligned with national and regional development strategies (see figure 20). In addition, in most BRI countries, China has focused on building partnerships mainly with central governments and high-ranking officials. There is still a need for Chinese enterprises and officials to engage more with local communities on projects.

In Uganda, the Export-Import Bank of China provided 85% of the funding for the Isimba Hydroelectric Power Station. Built by China International Water & Electric Corporation, the 183 megawatt power station is the third-largest in Uganda and was built to address the country’s power shortages. The project required 3,000 workers, 85% of whom were Ugandan.

“More emphasis should be placed on the mix of workers – local versus Chinese – and how the selection process is done,” said a central bank from the Caribbean region. “The working environment should have basic amenities suitable for a proper working environment. Also, more co‑ordination is needed with various local government agencies to ensure smoother completion of the project.”

The survey results reveal that two-fifths of the respondent central banks are actively advising their government and state development bodies about the BRI. With the exception of one central bank from Europe, all of these respondents represent emerging market and transition economies, where central banks tend to play a more active role in a country’s economic growth and development.

Unsurprisingly, the actions of China’s central bank have been crucial in supporting the project. As of May 2019, the People’s Bank of China has signed bilateral local currency swap agreements with 21 central banks in countries participating in the BRI.

Advisory responsibility more generally, however, sits with the relevant government departments. In these instances, government bodies – including domestic ministries of customs and trade, economic development, finance and foreign affairs – tend to be the driving force. Given the scope of the projects, it is unsurprising they are responsible for BRI-related matters. Nevertheless, as the scope of the BRI continues to expand, it may become crucial for central banks and financial regulators to take a more prominent role.

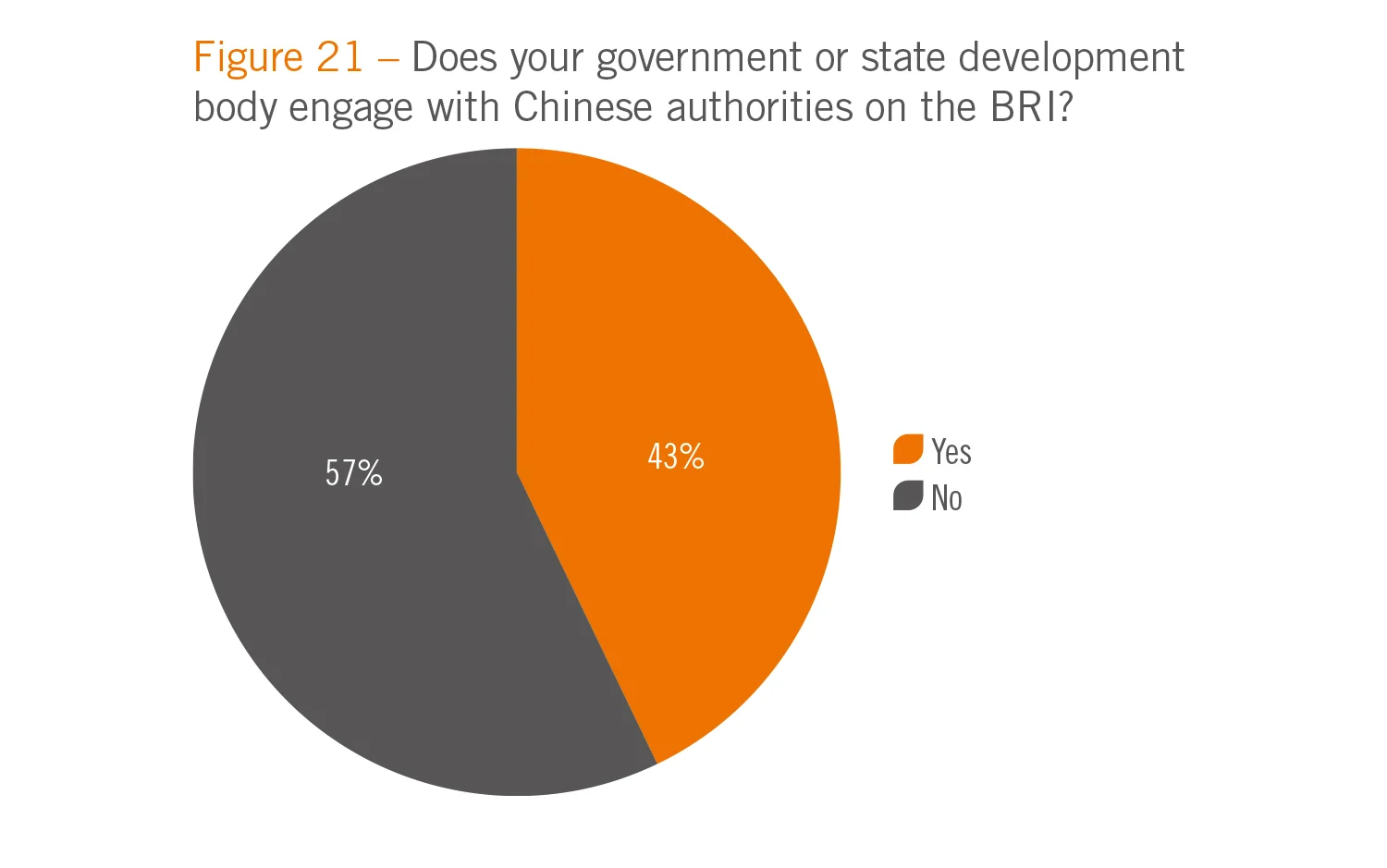

In addition to government departments, central banks taking a more active advisory role also tend to engage with Chinese authorities (see figure 21). This includes central banks from Asia, Europe and the Middle East, which indicates there may be little pattern when analysing the results by region of state of development.

Project selection was ranked as the second most important aspect of the BRI requiring improvement. While there tends to be discussions between governments regarding project selection, there remains a risk of stranded infrastructure if BRI projects are not included within wider strategies. Respondents also expressed a need for improved financial and project management support from the development banks involved in the projects.

Current challenges

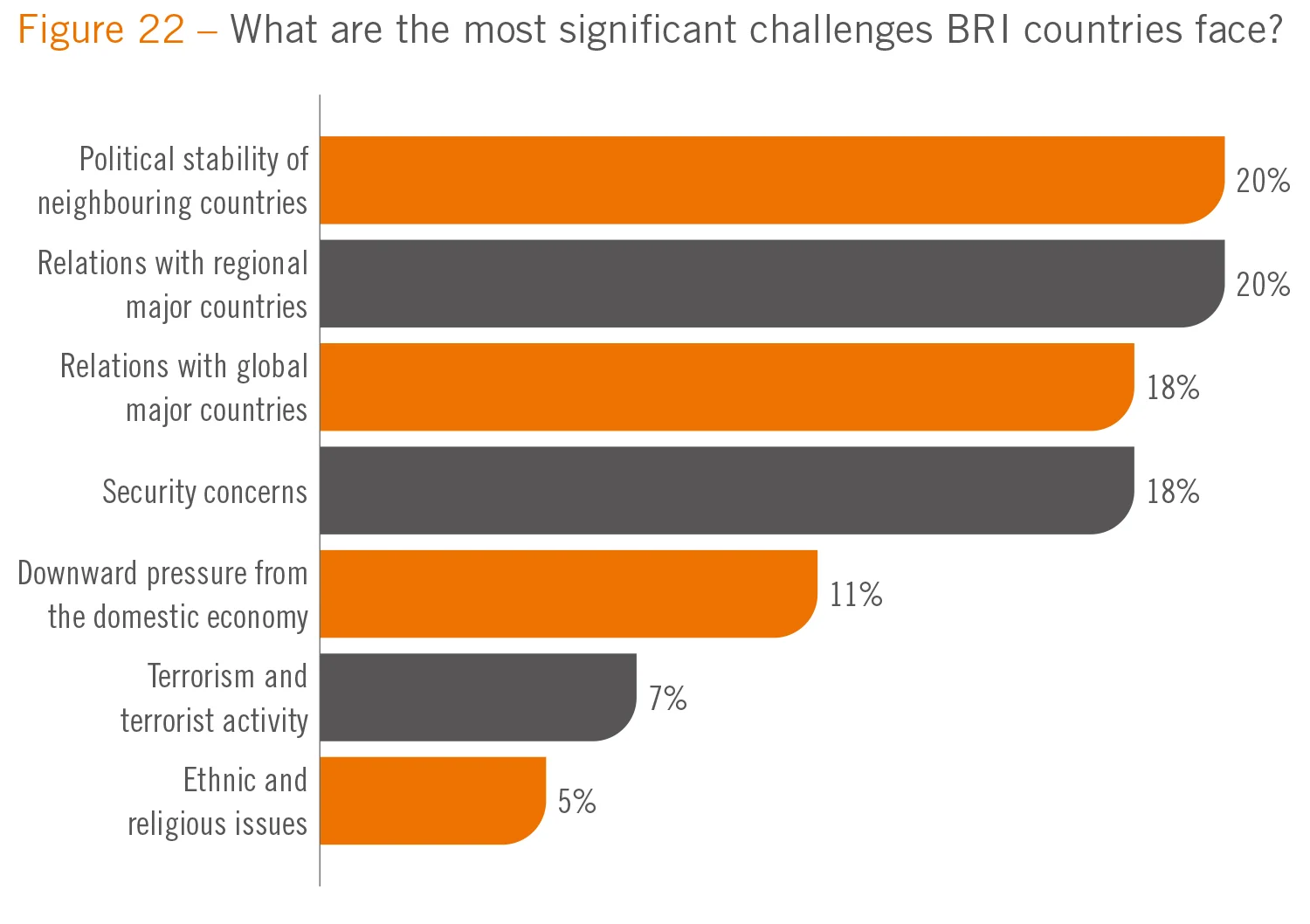

There is no doubt the BRI faces challenges. But, against a backdrop of tense trade relationships among the major trading blocs, the BRI has continued to gain a strong foothold. Indeed, BRI countries may have benefited from a fall in Chinese investments in the US. At its peak in 2016, the US accounted for roughly one-third of China’s overseas investments according to China global investment tracker, which looks at deal sizes of $100 million and above. Since President Donald Trump took office, Chinese investments in the US have plunged. It is therefore not surprising that 20% of respondents view political stability as a significant challenge.

Nonetheless, maintaining good relationships among BRI members will be crucial in the future. Respondents noted relations with major countries worldwide (18%) and within their region (20%), as the most significant challenge (see figure 22). “Other major countries could begin to get concerned regarding China’s expansion globally,” a Caribbean central bank said.

Managing relationships through election cycles also remains a challenge for Chinese officials. Projects can be susceptible to renegotiation risk, as demonstrated in 2017, when Malaysia looked set to terminate BRI projects following a general election. However, a year later, the government revived transport and property development projects with China, but the cost of the projects was reduced by one-third from $16 billion to $11 billion, according to research by Wharton University. Myanmar, too, has downsized a BRI-related port project from $7.5 billion to $1.3 billion.

Overall downward pressure on domestic economies was only listed as a concern by 11% of respondents. The new Debt Sustainability Framework for participating countries of the Belt and Road Initiative, combined with looser monetary policy in the US, appears to have stemmed ‘debt trap’ fears. Following extraordinary action from the Federal Reserve in March, emerging markets may feel their debt burdens lessening some more – at least in the short term.

The 2019 Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) Survey

In 2018, the IFF, in collaboration with Central Banking, inaugurated the BRI survey. Last year, with responses received from 28 global central banks, the findings concluded the BRI would support globalisation. However, there were concerns projects under way were not in line with current climate goals. The 2020 survey reveals the BRI debt is viewed as sustainable compared with other forms of external debt, particularly given it is often proportionally less significant.

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@centralbanking.com or view our subscription options here: www.centralbanking.com/subscriptions

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com