The calm before the storm – The climate change 2019 survey

Executive summary

- Central banks do not typically consider climate change a major risk to financial stability, although this is changing, notably among industrial countries.

- Climate change is clearly a concern for central banks – and a key concern for some – but not all consider it an issue they as institutions should directly act on.

- The insurance and banking sectors are the areas of the economy where central banks believe climate change will have an impact.

- Most central banks do not collect data directly related to climate change risk, but a growing number are assigning resources to this and developing capabilities.

- Stress testing risks derived from climate change is in its infancy among central banks. But this will likely change in the near future.

- Green assets are becoming increasingly attractive as an investment proposition for central banks, which regard green credentials as criteria that should be taken into consideration in reserve management.

- The use of environmental, social and governance (ESG) criteria in balance sheet management is the preserve of a minority of central banks.

- Central banks do not think they have the tools to promote green sectors. Many contend this is beyond their mandates.

- An overwhelming majority of central banks do not require commercial banks to disclose their climate-related risks.

- Central banks do not in the main think it necessary to add a specific section to their mandate in order to mitigate climate change risks, although a significant minority think a change should be made.

Profile of respondents

The survey questionnaire was sent to 100 central banks in March 2019. By the middle of April, responses had been received from 34 central banks. The central banks responded on the condition of anonymity, and that neither the banks nor their officials would be cited in this report. Of these 34 respondents, 44% were from Europe and 41% were from emerging market economies. Almost all central banks that took part are from countries that have signed the Paris Agreement on climate change.

Percentages in some tables may not total 100 due to rounding.

Does your central bank view climate change as a major risk to financial stability?

Central banks do not typically see climate change as a major risk imperilling financial stability. However, it is becoming a concern among central banks from industrial and emerging market economies. Six central banks – or 21% of those who answered the question – said they consider climate change a significant risk that could have a negative impact on financial stability. Central banks from industrial economies made up more than half of this group, and one-third were from emerging market countries. A central bank from an industrial country explained its thinking, noting the impact on the bank as an institution and, more broadly, the system it oversees: “Financial risks from climate change have the potential to affect the bank’s core responsibilities both for the safety and soundness of the firms we regulate and for the stability of the financial system.” Several respondents who consider climate change a major risk to financial stability believe it is vital to tackle the issue in its early stages rather than allowing it to develop into an even bigger threat. “The risks to financial stability will be minimised if the transition begins early and follows a predictable path,” said one.

However, out of the 28 banks that provided an answer to this particular question, 22 (79%) indicated they do not view climate change as a major risk to financial stability. This group was clearly dominated by central banks from emerging market economies, which represented 50% of the group. Transition countries were second with 23%, followed by industrial and developing economies at 18% and 9%, respectively.

Is financial stability part of your central bank’s mandate?

Interestingly, climate change has emerged as a financial stability issue. Typically, central bank engagement with climate change initiatives has been couched in terms of this element of their mandate: climate change is not usually regarded as an issue for monetary policy.2 While most respondents said financial stability is a part of their mandate, in the main they have yet to fully integrate climate change with that.

Which best represents your central bank’s view of climate change?

Climate change is clearly a concern for central banks, and a key concern for some, but not all regard it as an issue that they as institutions should act on. Twenty-four central banks – almost three-quarters of respondents – reported it was a concern they were either monitoring or acting on. The group of 21 that said they were monitoring was dominated by emerging market economies, which made up just over half, followed by institutions from industrial economies, which accounted for 43% of the total. The three central banks that said they were actively responding to climate change were all from industrial countries.

A minority of respondents stated that climate change is an issue, but one for other institutions to worry about. In other terms, of the 33 central banks that responded, 27% said that climate change is indeed an issue, but that they fail to see a role for them in the fight against it.

This body of respondents was dominated by central banks from transition countries, which comprised 45%. Institutions from emerging and developing economy countries followed suit, with each taking a share of 22%. Central banks from industrial countries were the least prominent in this group, with an 11% share.

On which area(s) of your economy will climate change have an impact?

The insurance and banking sectors are the areas of the economy on which climate change will have an impact. This was the view of the overwhelming majority of respondents, with 87% and 80% choosing them, respectively. In addition, just over 70% thought climate change would impact productivity. Overall, 24 (77%) central banks chose both insurance and banking and 17 (54%) selected the three most popular choices: insurance, banking and productivity. Of the 27 that chose insurance, most were from industrial or emerging market economies, with shares of 45% and 37%, respectively. The less prominent in this category were the central banks from transition countries, with a score of 11% and developing markets, with 7%.

One central bank from a transitioning market economy stressed the pervasive effect climate change could have: “Climate change has a certain degree of impact on most of the sectors, but none of them could be singled out.” This was echoed by a central banker from an archipelago country: “All aspects of the economy reflect the risks associated with climate change, increased numbers and intensity of tropical cyclones and hurricanes, as well as the potential rise in sea levels.” A central bank from an industrial economy noted it was at an early stage in thinking about the impact: “We are at the stage of preliminary screening analysis of potential impacts, and are considering all these areas.” Among the 25 central banks that indicated the banking sector would be impacted, just over one-third were from emerging markets.

In addition to the economic sectors included in the survey, some participants added climate change could have a negative impact on other economic spheres. One central bank from an advanced economy sees “climate change as having an impact on natural resource industries, in particular the energy sector. The potential of stranded assets in this sector could have an impact on productivity by reducing the capital stock.”

Although the previous question indicates that only a small percentage of respondents view climate change as a key concern that they are acting on, this question reveals how central banks see climate change as having a negative impact on these areas of the economy – sectors that include industries directly or closely related to the central banking system.

Data to analyse climate risk is often lacking. Does your central bank collect data specific to this issue?

Most central banks do not collect data directly related to climate change risk, but a growing number of institutions are developing capabilities in this area. Overall, 15% of respondents said they collect specific data to analyse climate risk. All of the institutions gathering this information are European, except for the central bank of one small

South-east Asian economy. In data collection, industrial economies are clearly in the vanguard. They represent 60% of the total of institutions collecting this information.

In contrast, 85% of respondents reported that they do not have this capability. The Network for Greening the Financial System – the group of central banks and financial supervisors created in the wake of the Paris Agreement on climate change – has recently flagged the importance of data collection.3 This group of 28 survey respondents is mainly made up of central banks from emerging market and industrial economies, which represent 43% and 36% of the total, respectively. These two types of economy were also the most prominent among those that reported they are closely observing the processes and possible consequences of climate change.

Nevertheless, several central banks are actively trying to overcome this challenge: “Even though, at this moment, no climate risk analysis has been conducted, an interdisciplinary group within the bank was recently appointed to address this matter,” said an emerging market central bank. Central banks that already have procedures in place and are collecting data are also trying to improve: “We already collect data relevant to climate risks as part of our standard regulatory data collections,” said an institution from an industrialised economy. “We plan to collect more specific climate risk data in the future.”

A disruptive energy transition

In 2018, the Netherlands Bank (DNB) carried out an exercise to better understand how a disruptive change in the energy model of the country could impact financial stability.4 This followed the recommendation of the European Systemic Risk Board in 2016 that European supervisory authorities should include a disruptive energy transition scenario into their stress-testing exercises.

The rationale behind the test was that – although the transition to an economy predominantly reliant on clean energy sources is a long-term process – it can generate risks in the short term. “In the transition to a low-carbon economy, risks to financial institutions and financial stability may arise,” said the DNB. “In particular, technological breakthroughs or abrupt changes in government policy may trigger a reassessment of asset values that could affect financial institutions’ balance sheets.”

For instance, if governments decided to implement carbon taxes or restrictions on carbon dioxide emissions, this could rapidly increase the costs of energy producers, airlines or infrastructure groups. “This is especially the case if such measures are implemented abruptly, as this would leave little time for firms to adapt to the new policy,” said the DNB.

In its first comprehensive report, the Network for Greening the Financial System also included in its four recommendations for central banks “integrating risks derived from climate change into their macro and micro supervision”. The DNB’s study found that “the losses for financial institutions in the event of a disruptive energy transition could be sizeable, but also manageable”. The central bank says the stress test allowed it to understand that individual institutions can mitigate portfolio risks taking energy transition risks into account. And policy-makers can ease this change by implementing timely, reliable and effective climate policies. Although the study provided valuable insights, the DNB acknowledged that “as stress testing energy transition risks is a relatively new field of study, future work could help to further refine the results”.

Does your central bank include climate-related risks in its stress tests?

If no, which best represents your central bank’s view?

Stress testing risks derived from climate change remains in its infancy but, while most central banks have yet to adopt and develop the procedures needed to develop these capabilities, this is likely to change soon. Seventeen central banks (59%) said they are either actively considering climate-related scenarios or looking to implement climate-related scenarios in their stress-test models. This group of countries was diverse, with equal numbers of advanced and emerging market economies, and with representation from all continents. Only one respondent, a central bank from an advanced country, said it includes climate-related risks in its stress-test exercises.

One major European central bank reported it has not incorporated climate risks in its stress-testing exercises but plans to in the future. Another European central bank has carried out exercises, but said it does not integrate climate related risks in its regular stress tests. In South America, a mid-sized central bank acknowledged its analyses of the financial system “include only credit, market, liquidity, and funding and contagion risk arising from hypothetical, adverse macroeconomic shocks”.

Would your central bank consider buying green assets in a quantitative easing programme?

reen assets are increasingly attractive as investments for central banks, and a minority of respondents (43%) said they would consider buying them in a quantitative easing programme. This group was comprised mainly of advanced economies whose central banks have carried out unconventional monetary policies after the financial crisis. In contrast, 57% of central banks ruled out that possibility. This group is dominated by emerging and transition economies from Latin America, Africa and Europe, although one central bank from a European advanced economy was also part of the group.

What proportion of bonds purchased following the financial crisis were from the manufacturing, electricity and gas sectors?

The bond-purchase programmes implemented in the aftermath of the global financial crisis have not led to major exposures to carbon-intensive sectors. More than two-thirds of respondents said they have not acquired assets from the manufacturing, electricity and gas sectors. Over one-quarter of respondents said the share of bonds they acquired from these sectors is 1–25% of their overall purchases. Just 5% of institutions addressing this question said the share of their bond buying was 26–40%. One European central bank said its “corporate bond portfolio is screened for violations against UN Global Compact norms”.5 As a result of these tests, some companies were removed from its investment in the past 12 months.

The pressure on public institutions to review their exposure to carbon-intensive industries is only likely to increase. Although central banks are not divesting rapidly now, other public entities are. On March 8, 2019, the Norwegian Ministry of Finance proposed to “exclude companies classified as exploration and production companies within the energy sector from the Government Pension Fund Global (GPFG)”. As the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund, with around $1 trillion under management, the GPFG is often used as a benchmark by institutional investors. Its ESG investment requirements have resulted in the exclusion of dozens of firms from its portfolio.

Should reserve managers take green credentials into account when deciding on asset allocations?

Central banks increasingly see green credentials as a precondition when choosing reserve assets. Sixty-nine per cent of respondents said reserve managers should take these factors into account when making investment decisions. This group is diverse geographically as well as economically. Over half were from emerging market economies and 40% from advanced countries. Within this group of 16, most said this would be beneficial for society as a whole and would also yield financial benefits. A smaller group were of a similar view that it would be good for society, but failed to see any clear financial gain. A northern European central bank firmly believes in the necessity to evaluate the green credentials of its investments: “In investing on behalf of a third party, we expect investee companies to assess how exposed their long-term business strategy and profitability are under future climate risk scenarios.”

In contrast, almost 22% of respondents do not think these considerations should be in central banks’ mandates, and two say assessing green credentials is not the role of a central bank. A small European central bank explains the latter perspective: “Given the role of foreign reserves to shield the economy against potential shocks and vulnerabilities, tailoring central banks’ investment policies towards the specific class of assets may endanger the main objectives of foreign reserves management – which are safety, liquidity and profitability, in order of priority.” This investment approach concedes that central banks could allocate certain parts of their portfolios to green assets within the standard management, “but only if they meet standards for inclusion in the list of eligible assets for foreign reserve investments, which mainly consist of investment-grade fixed income assets”, the European institution adds. A major European central bank largely shares this position. It emphasises that the main purpose of foreign reserves is to ensure the central bank, at any given point in time, has sufficient liquidity in foreign currency to conduct foreign exchange operations. “Our portfolio is therefore composed of the most liquid and creditworthy fixed income assets in a few major currencies, leaving little room for a climate-related objective.”

Halfway between these points of view, a southern European central bank acknowledges that “sustainability issues are important, and central banks – being among the largest official sector investors – should explore the social impact of incorporating ESG criteria into their investment decisions”. However, it adds that “at this moment in time the academy and industry research is inconclusive on the financial gains derived from taking them into account”.

Does your central bank use ESG criteria when managing its balance sheet?

Incorporating ESG criteria into balance sheet management is the preserve of a minority of central banks. Just over one-quarter of respondents said they use ESG – a group dominated by central banks from industrial countries. A big holder of reserves from Europe said it uses “voting rights in a part of our stocks portfolio to contribute to good corporate governance”. Additionally, it also has “an exclusion policy in place to exclude firms from the asset universe on the basis of not fulfilling our minimum ESG standards”. These criteria are implemented based on the product(s) these companies make, as well as on their labour and production practices. While lacking an official ESG policy, a small Eastern European central bank “closely monitors developments in the area and seeks to contribute, where possible, to mitigate climate-related risks”.

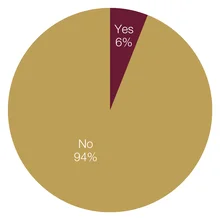

Is your central bank able to explicitly promote green sectors?

Central banks regard themselves as ill-equipped to promote a greener economic system. In total, 94% of respondents said they lack the tools to specifically promote green sectors.

A majority of respondents in this category – 41% – come from emerging market economies. They are followed by central banks from industrial countries, accounting for 35%. For one respondent, the reasoning was clear and could be traced back to their mandate: “Supporting broader social goals and priorities are beyond the mandate of the national bank. The tools of the central bank are designed to facilitate successful fulfilment of the final goals of the bank – sustaining price and financial stability in the country,” said one central bank.

Only a small minority of institutions say they have the tools to explicitly promote green sectors. Two respondents – one respondent from an industrial country, the other from an emerging market – say they have the resources and mechanisms to ease the economic transition to a less carbon-dependent system. One example of these measures is applying a discount rate to investments in the green sector. “Having a low discount rate for credit to the green sectors would help their development and provide incentives to invest into them,” said the participant from an emerging market economy.

In addition, only a handful of respondents said they would consider implementing specific policies to promote green sectors. The most popular was relaxing prudential regulation for green finance, which six respondents chose. Three said they would support credit for green loans, one of which commented: “Having a credit quota for green loans would be a good start; however, this requires another agency to certify what is green and what is not so the bank can evaluate the programme afterwards.”

Most comments received indicated that these policy options are not within respondents’ powers. “These considerations are not part of our mandate. Prudential supervision is carried out by a different institution,” said a respondent from an industrial economy. A central bank from a developing country said its “role does not include prudential regulation or requirements. This mandate is assigned by law to the supervisor of the financial system.” Another added: “Although supportive of the above [green initiatives], the central bank is not the prudential regulator for the country.” Another institution said “is not in charge of setting credit quotas or capital requirements. The answer to this question refers to the macro-prudential regulation set by the bank in the form of foreign exchange controls.”

Nonetheless, some institutions said they might be in a position to implement some of these measures in the future. One central bank from Oceania said “these possibilities will all be studied, but it is too soon to conclude what may or may not be appropriate”, in terms of its mandate.

Does your central bank ask commercial banks to disclose their climate-related risk?

An overwhelming majority of central banks do not require commercial banks to disclose their climate-related risks. Fully 94% of respondents do not ask banks for their climate risk exposure. One central bank in this category said it expects “financial institutions to be aware of climate scenarios that are relevant to them and to take appropriate action should they threaten to materialise.

We do not have a disclosure requirement at this point.”

However, central banks in this group are taking the first steps or considering amending their situations related to the disclosure of climate risks. “An initial letter to banks has been sent asking for information. This is a first step that could be followed by more specific disclosure guidance,” noted a central bank from an industrial economy. Another central bank from an emerging market economy added that it “is considering asking commercial banks this question”.

Of 31 respondents, two answered “yes” to this question. One of these, from an industrial market economy, commented that “this has been encouraged but not required. Disclosure is more of a focus for our prudential supervisor and our conduct regulator, which are different institutions.”

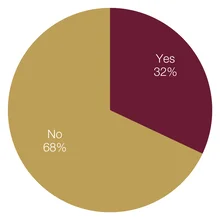

Should central banks have a specific section in their mandate to mitigate risks?

Central banks do not in the main think it necessary to add a specific section to their mandates to mitigate climate change risks, although a significant minority think a change should be made.

Over two-thirds of respondents rejected this possibility, while 32% said it could be a useful tool to tackle this global development. This larger group (of 17 respondents) was largely made up of emerging market countries, although six high-income economies were also in the group. Meanwhile, central banks from emerging market economies figured prominently among the eight in favour. One Caribbean-based respondent explained why it fully supported the idea: “Central banks could create funds to provide credit to green initiatives with a lower rate. Having a specific section [in the mandate] would definitely help designing the management process for such funds, and implementing a monitoring framework.”

In this regard, a regional divide appears among participants. Among central banks in favour of adding a specific section to their mandates to tackle climate change, 88% belong to non-western developing economies. Meanwhile, 53% of institutions that voted against the idea belong to industrialised western economies.

European central banks appear more reluctant to modify their current institutional frameworks than their peers from other regions. One major European institution thinks “to the extent that climate risks are proven to be relevant to central banks’ remits, it would help if this was explicitly in mandates”. However, another European central bank points out: “This would create potential conflicts of interest.” A southern European central bank noted it may not be necessary to modify mandates to add these risks to the rest of policy objectives. Climate change risks represent a threat to financial stability, and in doing so it could be argued that it is already embedded in mandates of central banks as guarantors of financial stability.

Notes

1.At the UN Climate Change Conference, which took place in Paris in December 2015, 195 countries adopted the first-ever universal legally binding global climate deal. The agreement set out a global action plan to put the world on track to avoid the dangers of climate change by limiting global warming to below 2º Celsius. As of March 2019, 195 member states of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change have signed the agreement, and 185 have become parties to it. The agreement’s long-term objective is to limit the increase in global average temperatures to well below 2° C above pre-industrial levels. Ideally, it aims to limit the increase to 1.5° C, as researchers believe this would substantially reduce the risks and effects of climate change. The agreement establishes that each country must determine, plan and regularly report on its efforts to mitigate global warming. The framework lacks a mechanism forcing members to set specific targets and timing, but each new objective should go beyond previous targets. As part of the agreement, authorities committed to build resilience and decrease vulnerability to the adverse effects of climate change. As financial systems transition to a low-carbon economy, banks and other institutions will need to shift billions of dollars away from fossil fuels and fill the gap with green investments.

2. Speech by Mark Carney made on September 29, 2015, Breaking the tragedy of the horizon – Climate change and financial stability. In particular: “There are three broad channels through which climate change can affect financial stability… First, physical risks: the impacts today on insurance liabilities and the value of financial assets that arise from climate- and weather-related events, such as floods and storms that damage property or disrupt trade. Second, liability risks: the impacts that could arise tomorrow if parties who have suffered loss or damage from the effects of climate change seek compensation from those they hold responsible… Finally, transition risks: the financial risks which could result from the process of adjustment towards a lower-carbon economy.”

3. In its first comprehensive report, published in April 2019, the Network for Greening the Financial System stresses the importance of sharing data of relevance to climate risk assessment and making it publicly available in a data repository. The report also calls on central banks to develop in-house capabilities to better understand the impacts of climate change on the economy.

4. W Heeringa, D Jansen, B Kölbl, M Lohuis, E Schets and R Vermeulen, The Netherlands Bank, 2018, An energy transition risk stress test for the financial system of the Netherlands.

5. The UN Global Compact (UNGC) is a non-binding UN pact that aims to encourage businesses globally to adopt environmentally sustainable and socially responsible policies. Governments and companies from 159 countries participate in the UNGC, which makes it increasingly difficult for carbon-intensive firms to avoid its scrutiny.

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@centralbanking.com or view our subscription options here: www.centralbanking.com/subscriptions

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com