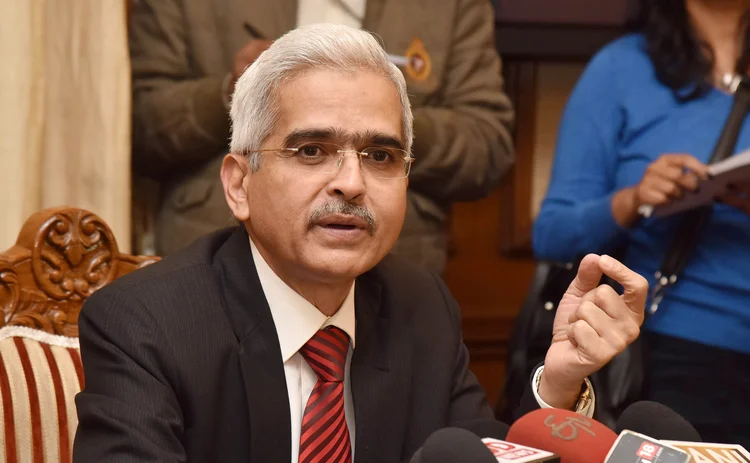

Governor of the year: Shaktikanta Das

The RBI governor has cemented critical reforms, overseen world-leading payments innovation and steered India through difficult times

On March 27, 2020, Reserve Bank of India governor Shaktikanta Das presented a monetary policy decision. Unusually, he did so to a room devoid of journalists. With Covid-19 spreading worldwide, the RBI’s monetary policy committee (MPC) had just held an emergency meeting and chosen to cut the policy rate by 75 basis points. Key staff had moved to an off-site ‘war room’ a few days earlier to keep critical functions operating as India entered lockdown.

“A war effort has to be mounted, and is being mounted, to combat the virus, involving both conventional and unconventional measures in continuous battle-ready mode,” Das said in the live-streamed address. “Life in the time of Covid-19 has been one of unprecedented loss and isolation. Yet, it is worthwhile to remember that tough times never last; only tough people and tough institutions do.”

It was one of the first deployments of a style of language that became a Das signature – offering not just reassurance that the RBI had the technical capabilities to master the situation, but also a human connection, recognising the anxiety and fear a billion people faced.

Covid-19 was no doubt the biggest crisis Das has faced so far as RBI chief. But his tenure, which began in December 2018, has been marked by a series of grave challenges, starting with the collapse of a major non-bank firm, moving through the first and second waves of the coronavirus, and then, in 2022, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and its inflationary impact. At the time of writing, there are new concerns about the risk exposures and potential contagion risks linked to public sector bank loans to companies linked to billionaire industrialist Gautam Adani. But it has also been a time of spectacular innovation for the RBI and for India as a whole.

Life in the time of Covid-19 has been one of unprecedented loss and isolation. Yet, it is worthwhile to remember that tough times never last; only tough people and tough institutions do

Shaktikanta Das

It is worth taking a step back to contemplate what was and is at stake. India is a country of 1.4 billion people, spread across 3.3 million square kilometres. Around a third of people live in cities, the rest spread across landscapes ranging from desert to rainforests to mountains. The services sector, including the increasingly large Indian tech sector, employs about one in three workers (and rising), and accounts for roughly half of the economic output. Agriculture still accounts for more employment, at about 40% of the labour force, but this is falling. The economy is developing at breakneck speed: GDP has risen some 90% in the past 10 years, and GDP per capita is up around 70%, giving the average Indian an income equivalent to $2,400 per year, $1,000 more than in 2010. Poverty is still widespread but has fallen from 55% to 16% in the space of 15 years on the United Nations’ multidimensional metric.

As one former RBI official puts it: “The kind of issues we are dealing with are on continental proportions.” And when Das took office, it looked like the financial sector could blow up at any minute, putting decades of progress at risk.

Non-banks in trouble

In August 2018, a few months before Das took office, IL&FS, a major non-bank financial company (NBFC), entered bankruptcy. The collapse triggered a liquidity crunch and exposed shortcomings in the business models of several mid-sized banks, some of which had lent large sums to NBFCs. A handful of other firms collapsed in the subsequent months, including Punjab and Maharashtra Co-operative Bank, which had lent heavily to an infrastructure finance firm that went bust.

Aspects of the response to the non-bank crisis had been put in place by Das’s predecessors in the governor’s office, Raghuram Rajan (a former Governor of the year winner) and Urjit Patel. Notably, IL&FS became the first NBFC to be resolved under a revised bankruptcy code, which the former governors fought hard to deliver. Other aspects took place solely under Das’s tenure, including the roll-out of liquidity rules for non-banks and closer supervision of key players in the sector. A new scale-based regulatory framework for NBFCs entered force in October 2022.

Although non-banks play an important role in the Indian financial sector, the bigger problem was the banking sector, which for years has exerted drag on growth and at times threatened to plunge the economy into crisis. Public-sector banks (PSBs) still have the deepest-seated issues. But whereas the sector looked to be in dire straits in 2018, with high levels of non-performing assets (NPAs), weak capital and little lending growth, there has been a steady improvement in the intervening years. In 2018, gross NPAs at PSBs were around 15% – by September 2022, that had fallen to 6.5%. Net of provisions, PSBs’ NPAs were 1.8% in September.

Undoubtedly, part of the impetus for the change had been reforms under Rajan and Patel, including the bankruptcy code and a ‘prompt corrective action’ framework. The government has also spent trillions of rupees recapitalising the PSBs. Meanwhile, several years of solid economic growth – Covid shock notwithstanding – have flattered bank balance sheets.

But Das has defended reform progress and driven it further himself. He shepherded the bankruptcy code back into legality after the Supreme Court overturned the previous version. He pushed banks to raise more capital, restructured the RBI to create a stand-alone supervision department, and established a College of Supervisors to train the next generation. The second edition of the RBI’s medium-term ‘utkarsh’ strategy – another Das innovation – has “refining the regulatory and supervisory framework” as a key plank.

Problems remain. The government retains control over key regulatory decisions on PSBs, such as the appointment or dismissal of senior managers. Many observers, including Rajan and former deputy governor Viral Acharya, argue the government must give up its controlling stake in the PSBs if the banks are to be truly reformed. With little prospect of that happening, in the near future PSBs are likely to continue to enjoy a degree of political protection, allowing them to ‘extend and pretend’ their bad debts a little longer.

The short-selling attack on Adani in late January triggered fears over major banks’ exposures. State Bank of India, a PSB and India’s largest lender, has exposures of $3.3 billion to the Adani empire, the bank’s chairman said, around 0.9% of the loan book. Rating agency Fitch estimates other Indian banks have lent Adani similar proportions of their loan books. Fitch described the exposures as “insufficient” in themselves to trigger a rating downgrade for the banks.

Analysts appear to believe an imminent crisis is unlikely and the first purchases of stressed debt by a new ‘bad bank’ may bode well for the ongoing sector-wide clean-up. The RBI has also worked to make best use of the powers it has. Supervisors are now demanding financial firms, including PSBs, maintain higher standards of governance, risk management, internal audit and compliance. Former RBI executive director G Padmanabhan says he believes PSBs still face shortcomings in their governance but are more resilient and continue to clean up their acts. “RBI is today a lot more direct and aggressive as supervisors and this has led to improvements,” he says.

None of this was a given, especially with the pressures that the RBI faced due to the pandemic.

Covid shock

Covid had a devastating impact worldwide, and densely populated India looked particularly vulnerable. It was in managing this crisis that Das had perhaps his greatest impact, appearing as a voice of calm amid the fear, and steering the RBI deftly between intense political pressures on one side and economic disaster on the other. The timely creation of a ‘bio bubble’ in March 2020 to quarantine key staff ensured the continuity of critical central bank operations throughout the most intense phases of the pandemic. Staffing in the bubble averaged around 200 over the 500 days of its operation, until it closed in August 2021.

It was in managing [the Covid] crisis that Das had perhaps his greatest impact, appearing as a voice of calm amid the fear, and steering the RBI deftly between intense political pressures on one side and economic disaster on the other

The Covid crisis threatened to throw the RBI’s work on the financial sector clean-up off-track. As the scale of the shock became clear, politicians and financiers clamoured for the central bank to allow banks to rollover and restructure troubled loans, rather than forcing firms into bankruptcy. This Das allowed, but only within tightly controlled parameters: banks could roll over problem debts only if they went sour after the pandemic began, and the regulatory forbearance was strictly time limited.

Das insisted similar ‘sunset clauses’ be applied to most of the RBI’s Covid interventions, some of which had never been tried before in India. The central bank offered long-term liquidity targeted at key sectors, provided foreign exchange, and used open market operations to keep liquidity ample. It slashed interest rates and granted state governments more generous terms on their overdraft facilities.

Perhaps its most significant policy was the government securities acquisition programme (G-Sap), which saw it buy ₹2.2 trillion ($26.6 billion) in government debt. Though substantially smaller than quantitative easing programmes in advanced economies, the policy could have been seen as putting the RBI at risk of fiscal dominance. However, G-Sap was confined to a narrow objective – securing market functioning – and was strictly temporary. The RBI used more standard liquidity operations to soothe market nerves as purchases ended, and has resisted calls for further purchases.

The RBI has also made judicious use of its reserves to cushion the impact of the major shocks India has faced. Although it is an inflation targeter, like many central banks in emerging markets, the RBI takes a broad view of stability, managing the exchange rate to prevent violent swings. In its latest Article IV consultation on India, the International Monetary Fund acknowledged that deploying reserves helped preclude the “emergence of disorderly market conditions”. At $560 billion in February, the RBI’s reserves cover around seven months of imports and are roughly double India’s short-term external debts.

The feared surge in NPAs due to the pandemic never materialised, and India enjoyed one of the fastest recoveries of any country worldwide. Das was forced to steer close to the wind in co-operating with a government that has frequently put the RBI under pressure to offer more forbearance than might be wise. But most observers think he got the balance broadly right.

Former RBI governor YV Reddy says Das has “quietly influenced” important government decisions, drawing on skills honed as a senior civil servant in the finance ministry. “Politics have become contentious and the judiciary overactive in its pronouncements on the financial sector,” Reddy notes.

Reddy described some of the complexities of navigating government relations in a speech in 2004, in which he highlighted the crucial values his predecessors as governor had demonstrated. “First, personal and professional integrity; second, capacity to make appropriate value judgements consistent with national ethos; third, and above all, willingness to appreciate the non-economists’ views on matters relating to reform.”

The government of the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party has sometimes strained this relationship. It has shown it is willing to intervene in RBI affairs, sometimes publicly, sometimes behind the scenes, putting successive governors in a tricky position.

Another former RBI official says Das has been more “sanguine” about government relations than predecessors Rajan and Patel, but has also created a more “pragmatic” working relationship. She notes the governor “stood his ground” in some past disputes with politicians, such as over the question of how generous to be in relaxing the banking sector clean-up during Covid. “Practically, I think that communication has worked well for central bank and government,” she says.

Indeed, communication has been one of Das’s key strengths. He has been active in giving speeches and talking to the media. He has also implemented reforms to allow other senior officials to speak directly to the press. Under his leadership, the comms team has started regular regional media briefings in which a deputy governor talks to press about the RBI’s initiatives. A spokesperson for the RBI describes the roll-out of a “360-degree public awareness campaign”, encompassing videos (a difficult production job in a country of 22 official languages), social media campaigns, including Instagram for the first time, and efforts to open two-way lines of communication.

Payments revolution

The pandemic added impetus to a trend in India that deserves the title ‘revolutionary’: the spread of electronic payments. The RBI’s Unified Payments Interface (UPI) has made instant electronic payments available to hundreds of millions of people and is seen widely as one of the most advanced payments platforms in the world. Rapid change has been possible because of the government’s roll-out of Aadhaar, a physical and digital form of ID, and basic bank accounts. India recorded nearly 50 billion real-time transactions in 2021 and almost certainly smashed that figure in 2022. The IMF says UPI has averaged growth rates of 160% annually since its launch in 2016.

ACI, a payments provider, says India is now the world’s largest real-time payments market. It attributes UPI’s “stunning” success to the fact that it is embedded in a wider, fast-growing financial ecosystem and that it is designed to act as a “flywheel” for innovation. The payments platform was initially only available for smartphone users, but underwent a major upgrade in 2021 to allow payments on other mobile devices. QR codes can be used to make offline payments and the RBI has proposed using them to allow cardless cash withdrawals. The RBI linked up UPI with Singapore’s PayNow on February 21, and more cross-border connections are planned.

“Mr Das is moving in a big way on payments,” says the former RBI official. She describes how it is now possible to leave the house without any cash and not worry about making payments. The absence of merchant fees has helped ensure UPI payments are offered near-ubiquitously across India, down to the smallest roadside vendors. “It is truly momentous. It’s amazing.”

As well as championing ongoing innovation around UPI, Das oversaw the project to make India’s real-time gross settlement system operate around the clock, every day of the year. The upgraded system went live in December 2020, making India one of the first countries to align with best practice now being championed at the global level by the Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures.

India is also near the front of the pack on central bank digital currency (CBDC), which the RBI is trialling in pilots for retail and wholesale systems. The rollout of an e-rupee to more than a billion people would be a project whose scale is matched only by China’s e-yuan. The RBI has said its CBDC will echo cash in its “trust, safety and settlement finality”, will not carry interest, and will allow digital payments using QR codes.

Just as decisively as Das has supported the work on payments and CBDC, he has opposed crypto assets in India. An early attempt to ban the speculative, blockchain-based assets was overturned by the Supreme Court, but the government has backed the RBI up on its sceptical stance, taxing crypto assets heavily without yet committing to a full ban. Even if Das does not get his way on a ban, it looks likely the RBI will keep the sector on a tight leash, which would be an important victory for investor protection and financial stability.

The future

An unresolved issue is inflation. The RBI was successful during the Covid crisis in supporting the economy and facilitating a rapid economic rebound. The problem came in late 2021, as the RBI, like many central banks worldwide, started to see prices rising. From around 4% (on target), inflation climbed to 7.8% in April 2022, outside the two-percentage point tolerance band. The RBI began a tightening cycle in the spring of 2022, adding 250bp to the policy rate since then to take it to 6.5%.

An economy as complex as India’s will likely never be free from challenges but, as Das faces up to the remainder of his second term, he can take pride in major achievements so far

Inflation has only just begun to show tentative signs of coming back down. It dropped back into the target range in November and continued down to 5.7% in December, but surged again to 6.5% in January, driven in large part by higher food prices. The surge surprised both private sector analysts and, likely, RBI economists, as both groups were expecting strong harvests and high levels of crop planting to curb food prices this year. Clearly, the MPC will not be able to rest easy for some time to ensure inflation expectations do not become entrenched at the top-end of the central bank’s target. Das will also have to guard against perceptions of fiscal dominance as the government comes to terms with the legacy of its Covid spending measures. A forthcoming general election, to be held before May 2024, may add to the pressure.

An economy as complex as India’s will likely never be free from challenges but, as Das faces up to the remainder of his second term, he can take pride in major achievements so far. The economy came through one of the greatest threats it has ever faced with relatively minimal scarring; India’s payments technology has rocketed to the global frontier; the financial sector is more secure than it has been for years. The Utkarsh strategic plan lays out a vision for continued governance reform at the central bank that should safeguard its position as a centre of excellence.

All RBI governors face the difficulty of working with governments that have different priorities to the central bank, and most will have to overcome crises during their tenures. But few have had to contend with challenges on the scale that Das has met. In the years ahead, Das will have to stand firm against interference and backsliding.

Reddy sums up the governor’s performance: “In my view, he has done an outstanding job in view of the extraordinary challenges he faced during the period and also the manner in which he had to negotiate the relationship with the government.”

The Central Banking Awards 2023 were written by Christopher Jeffery, Daniel Hinge, Dan Hardie, Joasia Popowicz, Ben Margulies, Riley Steward, Jimmy Choi and Blake Evans-Pritchard.

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@centralbanking.com or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.centralbanking.com/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com