After the super boom – China in the LAC region

Having reshaped investment and trading flows since the country’s reform and opening-up that began in the 1980s, China’s economy has expanded rapidly to become the second largest in the world. Chinese financing power has become so influential that the fate of the global economy is closely tied to sustaining the Chinese economy and its accompanying investments. Fuelling this success are waves of outbound investments, as well as Beijing’s capacity to finance developing countries’ economies. Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) countries illustrate the impact of Chinese foreign investment in the past decade, driving economic growth in the region. In fact, the commodities ‘super boom’ in LAC countries can be directly attributed not just to China’s increasing capacity to buy, invest in and finance LAC production, but to its overall capacity for consumption.

From 2010 onward, the world saw a gradual shift in focus away from investing in developed economies towards emerging ones. China and LAC countries have formed particularly strong ties in this context, with China now the largest foreign direct investor in LAC. Owing to changes in the international environment, such as increased Chinese multilateralism and US protectionism, Latin America–China relations have been moving gradually closer – particularly in the past two decades. This culminated in the establishment of a comprehensive co‑operative partnership between China and Latin America in 2014. This feature examines bilateral exchange in three key areas – trade, investment and financing – and then offers an insight into the scenario of China–LAC financing.

Trade

The growth of Chinese exports to Latin America has been impressive. The share of total LAC regional imports represented by China increased from 2.3% in 2000 to around 16% in 2017, with total trade reaching a value of US$258 billion – a transformation owed partly to China joining the World Trade Organization in 2001. Additionally, in 2000 China did not feature as a top-three exporter to any of the LAC countries, but today places first or second for all of the major countries in the region. China also imports significant amounts of LAC goods and resources, receiving 10% ($126 billion) of LAC countries’ total exports, which accounts for 7% of China’s overall imports.

Investments

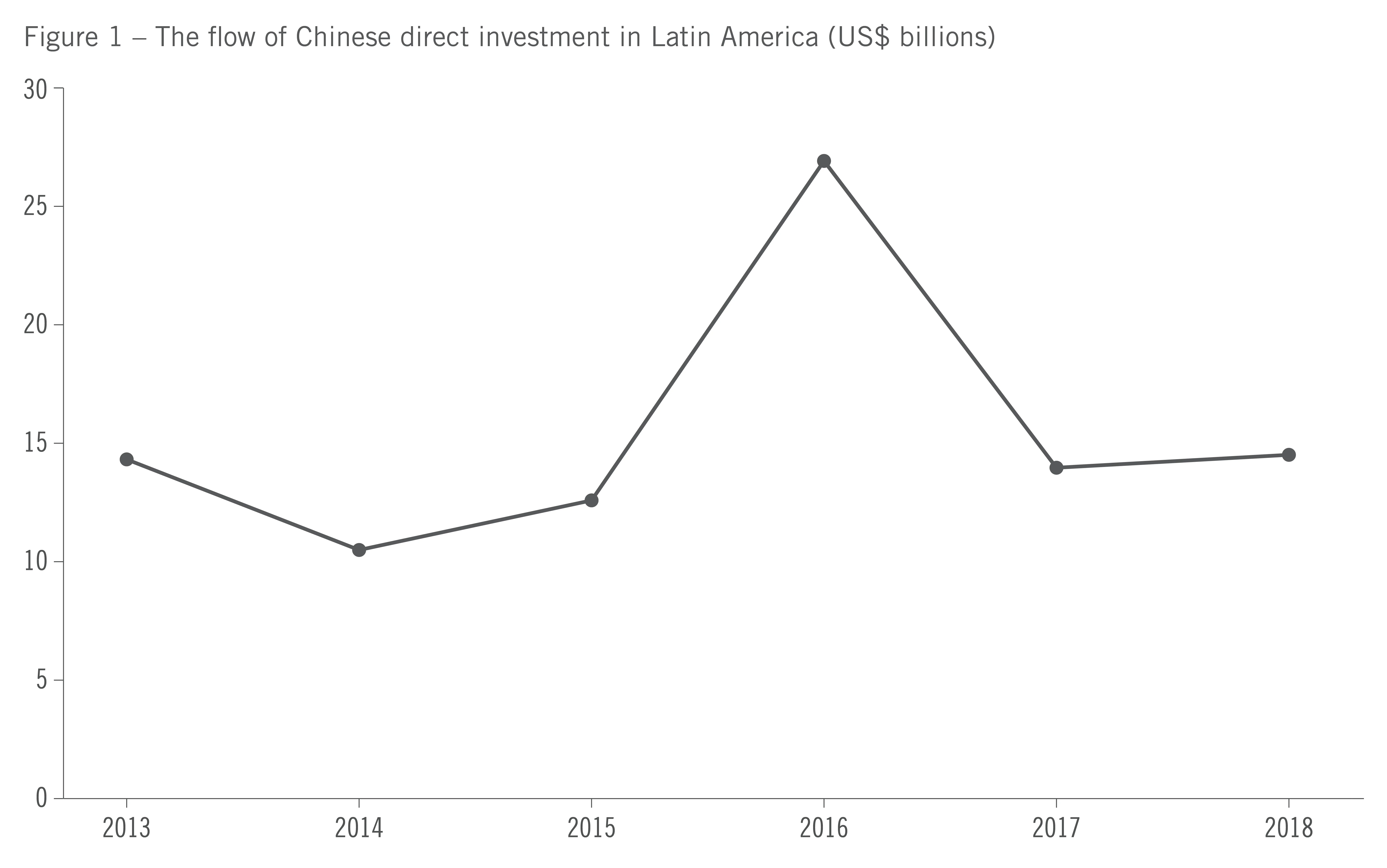

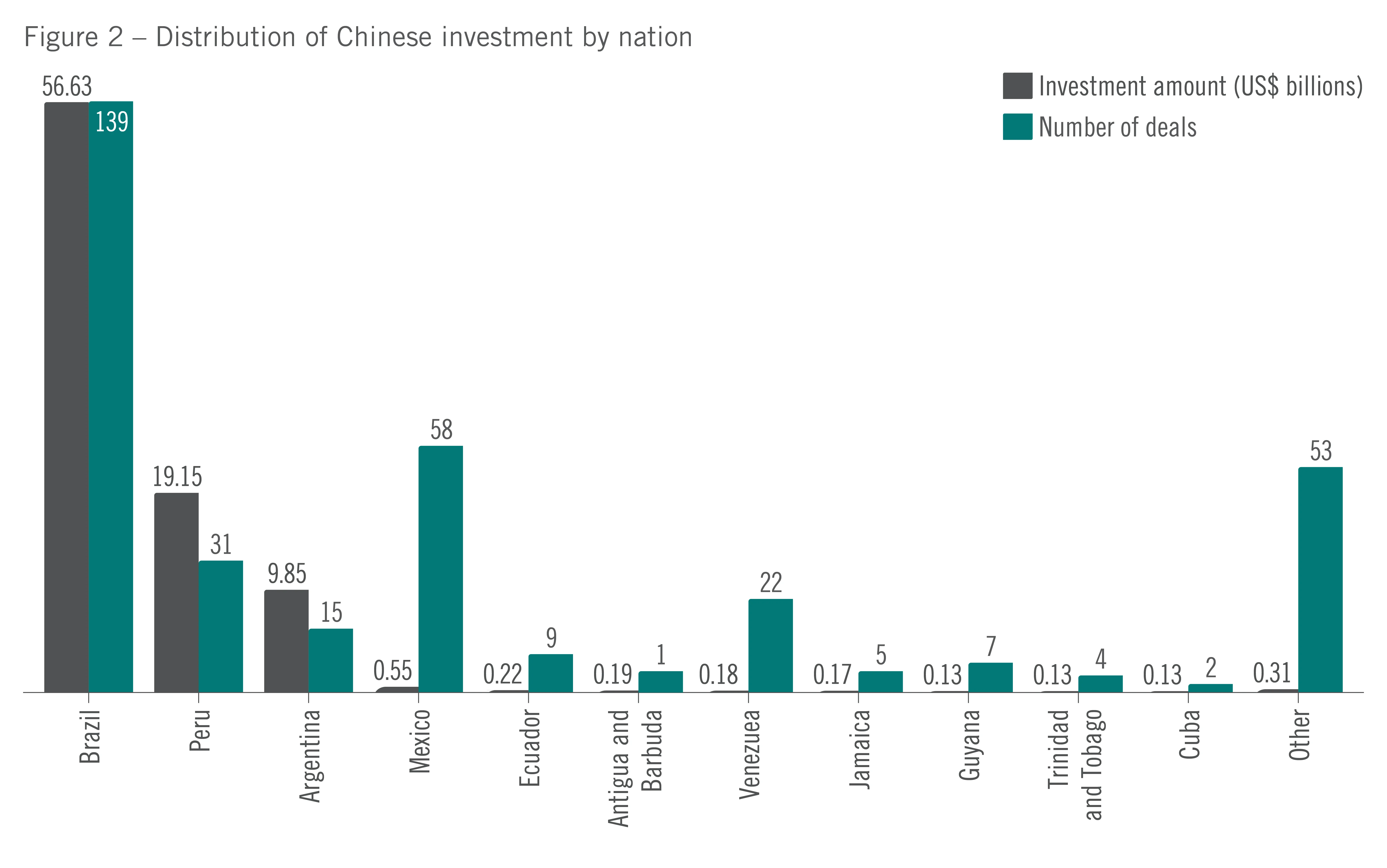

China’s outbound investments reached a record high of US$183.1 billion in 2016, making the country a net investor, with foreign direct investment outflows exceeding inflows for the first time. Investment by Chinese companies in LAC is estimated to be worth more than $25 billion, equivalent to around 15% of total investment in the region in 2017. According to the Chinese Ministry of Commerce, China’s direct investment in Latin America has already exceeded US investment in the region by $200 billion, making LAC the second-largest destination for Chinese overseas investment (see figures 1 and 2).

Mining was the most attractive sector for Chinese investment, receiving 27% of the total value of investments between 2004 and 2017, according to the World investment report 2018 by the UN Conference on Trade and Development.

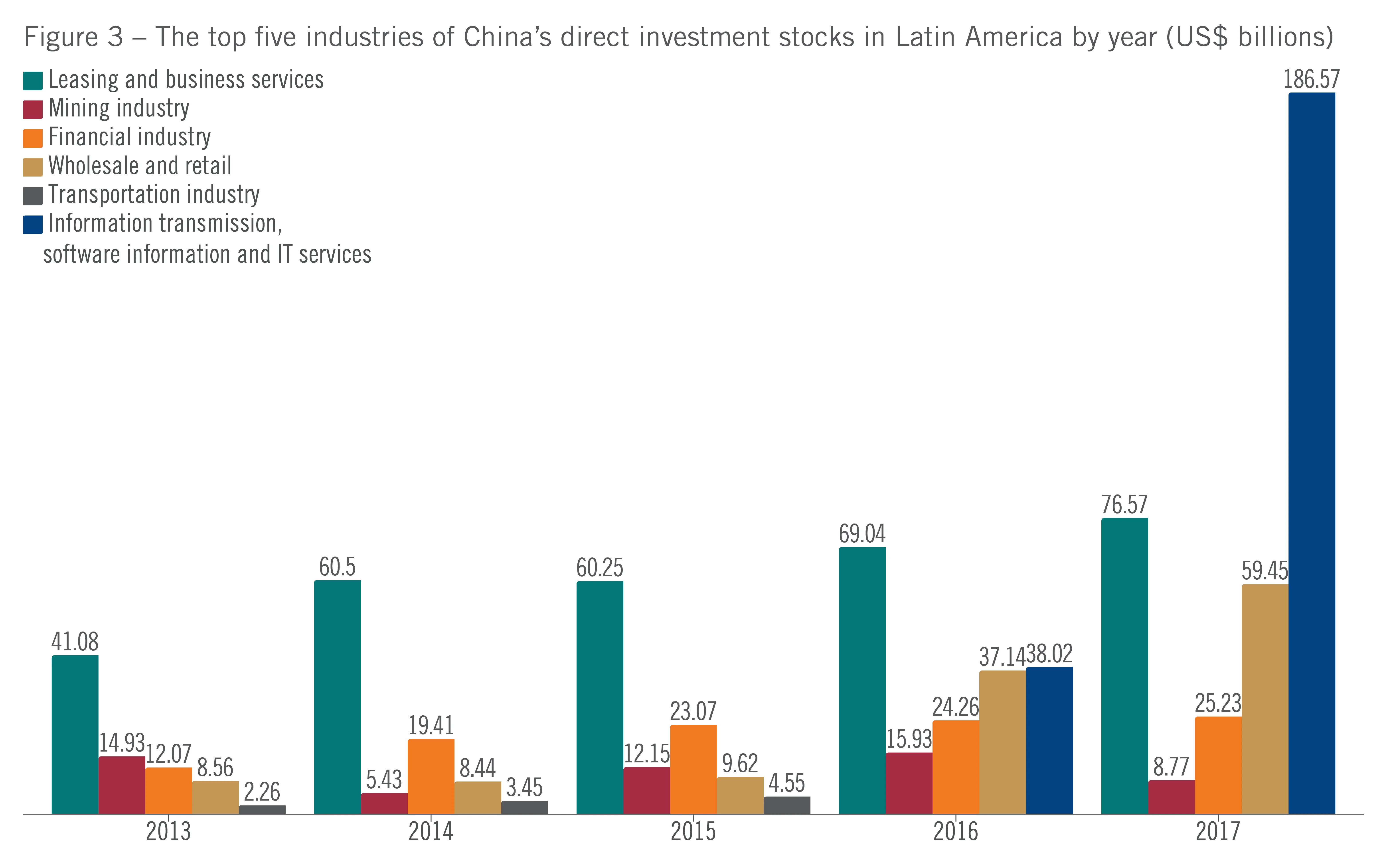

In recent years, however, there has been diversification of investment to sectors such as telecommunications, real estate, food and renewable energy, indicating Chinese companies’ appetite for entering new sectors in the region. Between 2013 and 2016, the leasing and business services industry was the number one sector receiving investment from China (see figure 3).

Financing

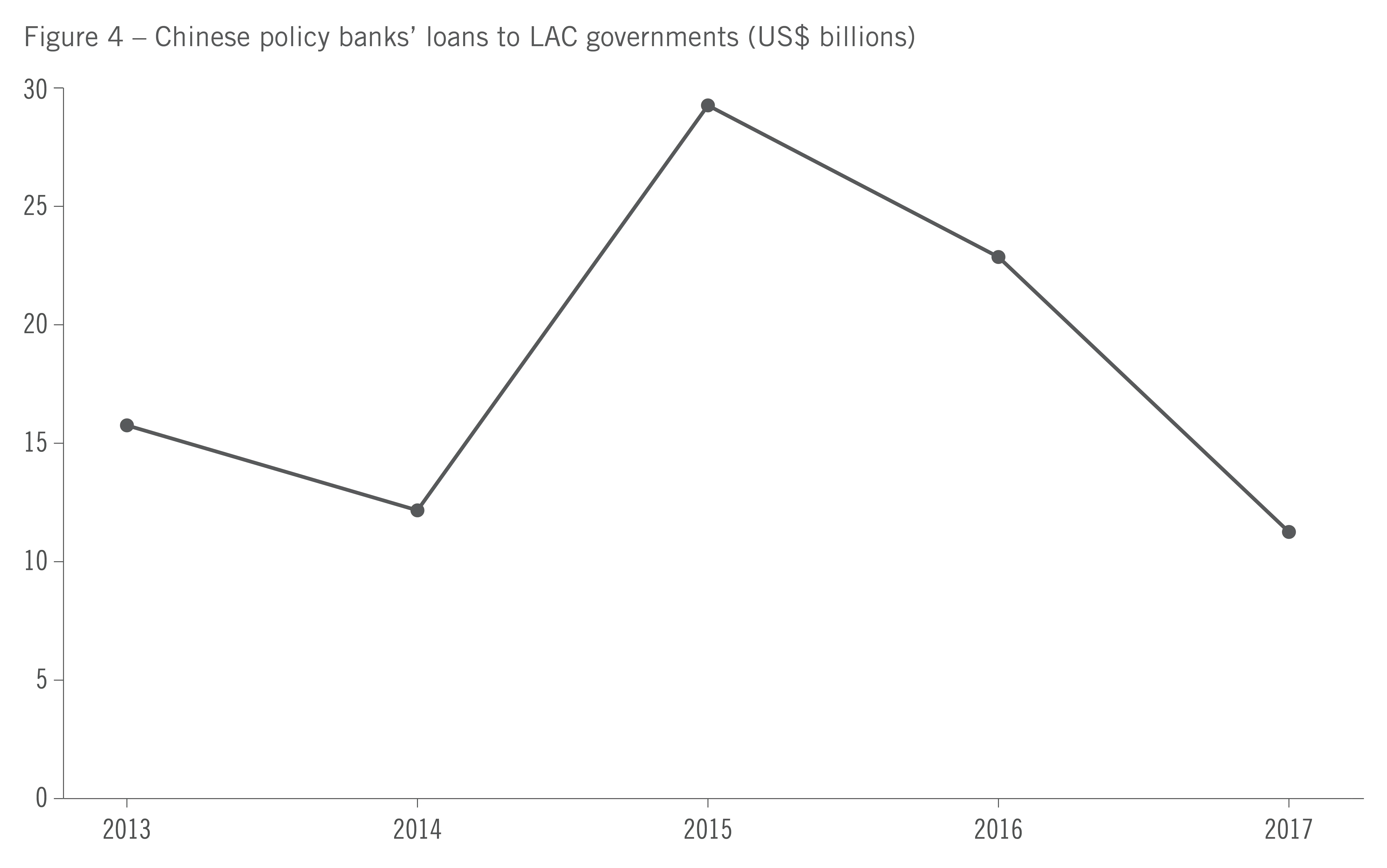

China–LAC financial flows have seen unprecedented growth during the last decade, often concentrated in infrastructure, energy and mining. Chinese lending has become the largest source of external financing for Argentina, Brazil, Ecuador and Venezuela – superseding well-established international financial institutions in the region. While 60% of total financing to Latin American economies comes from the bond market, bilateral loans only represent around 8% of total international financing, a proportion that has remained constant since 2005.

However, in certain countries – including Bolivia, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador and Venezuela – the proportion of bilateral loans has increased dramatically in recent years, most notably in the Dominican Republic and Ecuador, where the proportion of bilateral loans has increased by 12% and 26%, respectively.

Other LAC countries are actively engaged with Chinese financing – Argentina (16%), Brazil (19%), Ecuador (9%) and Venezuela (47%) accounted for 91% of Chinese loans between 2005 and 2016. Total investment by China in Latin America is expected to reach $250 billion by 2025, exceeding the $99 billion invested over the past decade.

While such loans are intended to complement the recipient country’s economy, loans made by major Chinese development banks to Latin American governments are primarily the result of the strategy to diversify China’s foreign exchange reserves with a view to promoting international use of the renminbi. These loans also support a strategy of assisting and directing Chinese enterprises to invest in natural resources.

Chinese loans aim to finance a few specific sectors, such as infrastructure, energy and mining, rather than the large number of sectors covered by traditional loans from international financial institutions. The role of China in the future of Latin America’s economic landscape, as well as wider impacts on international markets requires further evaluation.

Framing the investment relationship

Between 2005 and 2014, around 80% of total Chinese financing in Latin America supported infrastructure development, including partial or complete financing of hydroelectric dams, gas networks and turbines. Within this, telecoms represent close to 7% of total financing. Commodities accounted for the remaining 20% of financing – in particular, the Aluminum Corporation of China’s copper mining in Peru (roughly 9%), and other sectors, such as corporate and working capital operations. Almost 45% of total financing was directed towards transport infrastructure, including roads, airports, railways and metro networks.

These investments are expected to increase in the near future – especially in the areas of energy, oil and gas and infrastructure. As China takes up an increasingly prominent role in the global economy, LAC countries have shown themselves to be important partners. But it must first be established how to best co-ordinate this relationship.

Funding by Chinese and international organisations is facilitating LAC financing. China has increased its presence in the region through bilateral loans and its membership in multilateral development banks – from joining the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB) in 2009, to the launch of the New Development Bank operated by the Brics nations – Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa.

The China Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China have provided $150.4 billion in financing to LAC governments and their state-owned enterprises (SOEs), exceeding lending from the World Bank, the IADB and the Andean Development Corporation – Development Bank of Latin America combined. By comparison, the IADB approved $11.4 billion in sovereign-guaranteed loans to the region in 2017, while the World Bank lent $5.9 billion.

Specific regional funds targeting LAC countries, such as the China–LAC Cooperation Fund and China–LAC Industrial Cooperation Investment Fund, have helped China diversify its strategy.

The future of Chinese financing and the BRI

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is more expansive than its ancient predecessor, the Silk Road, and it is not limited to Asia and Europe. China formalised the LAC region as an extension of the BRI in 2017. The BRI has brought a host of development opportunities to Latin America, boosting the economy with transport and infrastructure projects. However, there have also been concerns regarding the financing of projects, particularly the potential for debt traps. With Chinese SOEs responsible for 70% of the BRI construction project contract value, questions surrounding the transparency of the procurement process remain, alongside environmental, labour and governance issues. These reservations from Latin America do not seem to have perturbed the Chinese government. President Xi Jinping predicts the total trade volume between China and Latin America will reach $500 billion by 2025.

LAC countries are using Chinese investment to fill their gap in infrastructure levels. There remains a significant investment disparity between more established coastal areas and often more remote inland areas, which hampers economic development. Initial investments have centred on infrastructure – such as China Merchants Port Holdings’ 90% acquisition of Brazil’s second-largest container terminal, located in Paranaguá. However, under the BRI, the scope for future investment co-operation will be more wide-ranging.

Latin America has become an important partner to China in supporting the BRI. A total of 33 countries in Latin America have established diplomatic relations with China, of which 19 have signed co-operation memorandums on jointly constructing the BRI.

Yet growing levels of exchange between LAC countries and China is not without its challenges. President Xi has described the globalisation of the LAC region as a double-edged sword. While it has fuelled and aided economic growth, it has also created social tension, due to further stratification of social classes and a growing middle class. The absence of a robust economic driving force and weak institutional governance has triggered rising levels of unemployment and income inequality, but with wider and more damaging effects in Argentina, Brazil, Venezuela and El Salvador.

Creating a shared community with a unified vision on development goals is essential. High levels of collaboration are necessary to demonstrate that the BRI is not a platform to further Chinese influence, but a co-operative one from which participating countries can derive benefit. The BRI in the LAC region will involve challenges and opportunities that need to be incorporated into a broader development strategy aimed at upgrading, diversifying and integrating. For this to happen, China also needs to understand Latin America’s development challenges. The willingness to establish channels of co-operation should go beyond bilateral forms of dialogue and include a structured dialogue with the region. A successful China–LAC partnership needs adequate multilateral governance.

One possible solution is for China to adopt the China–Community of Latin American and Caribbean States Forum as the main channel of communication with LAC countries. Participating countries can use this platform to propose a co-operation action plan for the region that encompasses the

following factors:

1. A specific governance system for China and LAC countries to implement the BRI in the LAC region, defining targets, priorities, actions and an implementation timeline.

2. A quantifiable target for exports to China and Chinese exports to LAC countries, in addition to the diversification of exports away from commodities to other sectors such as services.

3. The development of an infrastructure investment plan that would help reduce the infrastructure gap. This is crucial for the medium- and long-term growth for many areas in the LAC region. Furthermore, investment in infrastructure would benefit China by reducing the cost of commodities. If Latin America closes its infrastructure gap, the region could increase its annual growth by an estimated 2%–3%. To meet infrastructure needs between 2019 and 2025, Latin American countries should invest around 5.2% of the region’s GDP every year.

4. A science, technology and innovation co-operation plan where Chinese and Latin American universities, research institutions and companies can exchange knowledge, talent, technology and investments in innovation.

5. The exchange of successful policies for the creation of a social development programme that could be adopted in China and LAC countries for the reduction of poverty and improvement of healthcare, education and sustainability.

6. The creation of a China–LAC culture and sports exchange programme to connect societies and promote cultural awareness and exchange.

7. The clear communication by China of the benefits for LAC countries’ accession to the BRI. It is imperative that LAC countries understand that this initiative is not a solo Chinese initiative but a co-operative platform that already has a global governance system.

It is clear what is expected from all leaders is to solidify co-operation with the region. Latin America needs a comprehensive strategy to direct its engagement with the BRI. This strategy must promote comprehensive development based on the expansion of trading areas, improvement of infrastructure, increasing investment facilitation and new finance instruments to promote not just infrastructure development but also the exchange of science and technology. This can be achieved by putting forward a common agenda for the LAC region: to seize the opportunities to eradicate poverty and to pave the road to development.

The path for China and LAC countries to deepen and improve their partnership is clearly delineated, and achieving this should be an integral part of each government’s development agenda. China has been – and will continue to be – a game-changer for the future development of the LAC region.

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@centralbanking.com or view our subscription options here: subscriptions.centralbanking.com/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com test test test

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com test test test