Foreign direct investment inflows and FDI screening policies

Aditya Gaiha and Indrani Manna

Executive summary

Trends in reserve management: 2025 survey results

Fiscal divergence and its implications for reserve managers

Foreign direct investment inflows and FDI screening policies

Interview: Juliusz Jabłecki

Is the central bank gold rush over?

Market sentiment analysis in reserve management

Appendix 1: Survey questionnaire

Appendix 2: Survey responses and comments

Appendix 3: Reserve statistics

The views expressed in this chapter are those of the authors and not those of the Reserve Bank of India.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) flows are a durable source of capital for emerging market economies (EMEs). FDI is associated with transfer of technology and managerial know-how, productivity spillover to local firms and greater competition in local markets (Evenett, 2021). According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (Unctad), in 2023, world FDI stock stood at $49.1 trillion, which is 46.3% of global GDP. Developing economies accounted for 31.9% of the total FDI stock as of 2023. Global FDI flows, however, after rising to $1.6 trillion in 2021, have been steadily declining since the post-Covid period (see figure 1). While the declining trend may partly be attributed to tighter financing conditions and the volatility of financial markets globally, increased regulatory scrutiny imparting policy uncertainty to project financing and merger and acquisition deals have been factors in slowing down FDI flows, too. Since 2020, several jurisdictions around the world, including the European Union, US and Japan, accelerated the screening of FDI applications to prevent opportunistic takeover of weak companies during the pandemic by business entities in other countries.

The literature shows that beyond structural factors shaping FDI flows, several short-term factors including policy uncertainty have played a decisive role in driving FDI around the world. Foreign capital like FDI is more exposed to host country political and institutional uncertainty due to its long-term commitment to the local economy and higher sunk costs (Jardet, Jude and Chinn, 2022). Differential tax treatments and restrictive regulation on capital repatriation makes FDI difficult to reverse. Limited information about legal and political institutions in the host country further instils uncertainty among foreign investors. Further, accelerated scrutiny of FDI applications and demand for additional documentation is both time-consuming and expensive for foreign investors. It often propels the investor to take advantage of policy arbitrage opportunities and move their proposed investment into countries that are not pursuing any such policy changes and provide a relatively conducive and stable environment for investment.

This chapter looks at the impact of unanticipated austerity in FDI screening practices adopted in a number of countries between 2020 and 2022 on inward FDI flows. Most of the previous work exploring the connection between FDI and uncertainty have used panel regression analysis to estimate the effect of world uncertainty index database as a variable on FDI inflows: Nguyen and Lee (2021); Schmidt and Broll (2009); Solomon and Ruiz (2012); Asamoah et al (2016). Our work differs from earlier work in that it uses the difference-in-differences method to estimate the causal effect of policy uncertainty emanating from an unanticipated increase in regulatory scrutiny of FDI applications during the Covid-19 period by comparing the changes in FDI flows between a treatment group of countries that accelerated FDI screening during Covid-19 and a control group of countries that were not subject to such policy changes to obtain an appropriate counterfactual. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first article to evaluate the quantitative impact of FDI screening during Covid-19 on inward FDI flows.

Determinants of FDI flows

The major determinants of FDI flows found in the literature includes various push-and-pull factors. Panel regressions have mostly used variables such as GDP growth rate, trade openness, capital account liberalisation, exchange rate, fiscal spending, stock market returns and degree of financial development as pull factors. Global liquidity and risk measures such as implied volatility of S&P 500 index options are used as push factors (Kurul, 2017; Nguyen and Lee, 2021). Several country-level variables capturing the institutional characteristics of the destination country – such as control of corruption, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, rule of law and voice and accountability – are also included as explanatory variables of FDI flows. A sound regulatory and institutional environment is expected to provide an encouraging atmosphere for FDI flows by reducing the perceived risk associated with investment. Weak institutional quality – in the form of imperfect implementation of contracts, lack of protection of property rights, expropriation risk, corruption and political instability – exacerbates the cost of doing business in the host country deterring FDI inflows (Kurul, 2017; Julio and Yook, 2016).

Several papers (Jardet et al, 2022; Kurul, 2017; Nguyen and Lee, 2021; Julio and Yook, 2016) have highlighted the significance of policy uncertainty affecting cross-border capital flows. Julio and Yook (2016) examined the effects of political uncertainty on cross-border flows using election timing as a source of fluctuations in political uncertainty. They found that FDI flows from US companies to foreign affiliates declined significantly before an election in the destination country. Nguyen and Lee (2021) observed that countries with higher economic policy uncertainty received lower FDI inflows. Jardet et al (2022) find that global uncertainty rather than host country uncertainty is instrumental in explaining FDI inflows. A critical source of policy uncertainty with respect to FDI is increased regulatory review of FDI applications in the destination country. Demand for additional documents, revised application methods, longer waiting periods and prior approval through government routes infuse uncertainty into FDI flows. The section below elaborates on the recent policy changes with respect to screening of FDI applications in various countries.

FDI screening: recent experiences

Several jurisdictions – such as the US, EU and India – already have a framework in place for regulating foreign direct investment. For example, the EU framework for screening FDI entering the EU aims to prevent threats to national security and public order. It empowers the EU Commission to issue ‘opinions’ on inward transactions involving FDI within the territory of EU member states from non-EU countries, and has an exhaustive list of criteria for domestic screening by member states. Similarly, the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States enacted the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act of 2018 (Firrma) to address national security concerns regarding foreign investments. Firrma prescribes filing requirements for investments in certain sectors and entities, while CFIUS reviews investments pursuant to this law. The CFIUS assesses the potential threat of the foreign investors, the vulnerability of domestic business and national security implications of FDI entering the US.

India laid down a transparent, predictable and easily comprehensible policy framework for FDI embodied in its Consolidated FDI Policy. The Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade (DPIIT), Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Government of India, make policy pronouncements on FDI through Consolidated FDI Policy circular/press notes/press releases. These are notified by the Department of Economic Affairs (DEA), Ministry of Finance, Government of India, as amendments to the Foreign Exchange Management (Non-Debt Instruments) Rules, 2019, under the Foreign Exchange Management Act, 1999 (42 of 1999).

In the aftermath of the pandemic, several economies made FDI assessment regulations more stringent. On March 25, 2020, the EU released guidelines requesting member states to undertake rigorous screening of all foreign investments that can affect critical European assets and technology. This led to an agreement among member states to share all information on FDI transactions that could affect the EU. That same year, Germany stipulated that foreign acquisitions of at least 10% stock in German companies developing and manufacturing vaccines, medicines and medical equipment for treatment of highly infectious diseases required prior government approval.

In December 2020, Australia passed the Foreign Investment Reform (Protecting Australia’s National Security) Act 2020 to amend the Foreign Acquisitions and Takeovers Act (1975), and it introduced a compulsory prior approval requirement for any application for acquisition by a foreign person of a 10% or more share in a ‘national security business’. The term ‘national security business’ in Australian foreign investment policy encompasses responsible entities and direct interest-holders of critical infrastructure assets, businesses that develop, manufacture and supply critical goods, technologies or services that may be used by the defence forces of another country and businesses that own, store, collect or maintain classified data regarding Australia’s defence.

Similarly, New Zealand amended its Overseas Investment Act 2005, to impose mandatory notification requirements on all foreign investments leading to the acquisition of an interest of 25% or more. The UK mandated prior approval and compulsory filings for most types of acquisitions in specified sectors.

In 2021, Canada published new Guidelines on the National Security Review on Investments, stipulating a set of national security factors such as the potential of the investment enabling access to sensitive personal data to be taken into account by the authorities in their review of FDI transactions. In 2021, Malta amended its FDI screening procedure to include access to sensitive information or ability to control such information.

In 2022, US president Joe Biden issued Executive Order 14083, whereby CFIUS was directed to consider specific factors such as the impact of FDI transactions on critical supply chains, the technology leadership of the US in specified industries, and the risks to US citizens’ sensitive information. In sum, while some countries demanded additional filings, some rerouted applications through the government approval process, lengthening the duration of FDI approval and implementation.

Econometric strategy and methodology

The econometric strategy in this chapter uses the difference-in-differences method to identify the effect of increased FDI screening during the Covid-19 period (between 2020 and 2022). The difference-in-differences approach is a research design that estimates the causal effect of certain policy intervention and policy changes that does not affect everybody at the same time and in the same way (Lechner, 2010). The design hinges on comparing four different groups of objects: (i) the treated prior to their treatment (pre-treatment treated); (ii) the nontreated in the period before the treatment occurs to the treated (pre-treatment nontreated); (iii) the nontreated in the current period (post-treatment nontreated); and finally the (iv) group, which receives the treatment (post-treatment treated). The primary assumption behind this method for identifying the treatment effect on the treated is that without such intervention, the (conditional) outcome of interest experienced in both groups would have developed similarly over time. This is also known as the ‘common trend’ or ‘parallel path’ condition (Henderson and Sperlich, 2022). This states that there is a constant difference between the two groups, perturbed by this treatment. If the treatment has had no effect in the pre-treatment period, then an estimate of the ‘effect’ of the treatment in a period in which it is known to have none, can be used to remove the effect of confounding factors to which a comparison of post-treatment outcomes of treated and nontreated may be subject to.

The policy intervention referred to in this chapter is the increased screening of FDI applications in some countries initiated during 2020–2022.1 Although a cross-country phenomenon, the quality of intervention varied across countries. While in some countries, such as the UK and US, only additional documentation was required, in other countries, applications that were on an automatic route now required prior government approval (New Zealand and Australia). In some countries, such as Canada, new policy statements were released indicating that FDI applications from a particular set of countries must go through the government approval route. In 2022, Canada issued its Policy Statement on Foreign Investment Review and the Ukraine Crisis, indicating that, with respect to national security reviews, if an investment, regardless of its value, had direct or indirect ties to an individual or entity associated with, controlled by or subject to influence by the Russian state, such investment could be injurious to Canada’s national security and called for added scrutiny.

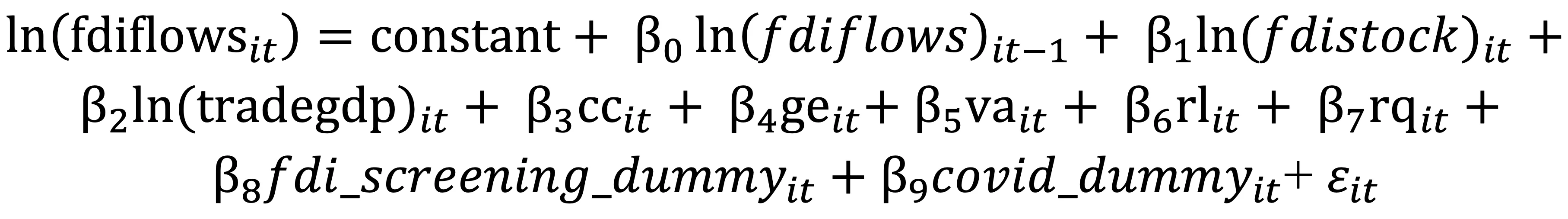

Our panel regression takes into account these differences in the quality of policy intervention. We conduct generalised difference-in-differences regressions with two different sets of policy dummies, which take into consideration the heterogenous time shocks embedded in policy-making at different points in time. One, a dummy that assigns a value 1 for all countries that initiated increased FDI screening during the 2020–22 period and zero otherwise. In other words, it is an interaction term of the countries treated, or which adopted a policy intervention on FDI, within the period during which such intervention happened. Thus it takes the value 1 for 15 countries including Australia, Austria, Canada, France, Germany, Hungary, India, Italy, Japan, Lithuania, New Zealand, Poland, Slovenia, Spain and UK. We call it ‘fdi_screening dummy 1’. Two, a dummy that assigns a value of 1 for countries that issued more stringent FDI policies during 2020–22 for applications received from a certain group of countries and zero otherwise. This would be referred to as ‘fdi screening dummy 2’. The impact of these two dummies on inward FDI flows in a set of 39 countries is observed in standard random effects panel regression estimated for the period Q1 2013 to Q3 2024 along with several other co-variates generally used in the literature as determinants of FDI inflows as shown below.

where fdiflows and fdistock refers to inward FDI flows and FDI stock with respect to the i-th country. Tradegdp is the trade to GDP ratio for i-th country. Governance indicators includes control of corruption (cc), government effectiveness (ge), rule of law (rl), regulatory quality (rq) and voice and accountability (va). Covid-dummy takes the value 1 for Q1 2020 to Q3 2022 period and zero otherwise for all countries. All variables are in natural logarithms. Our data satisfies the parallel trend assumption as required for the difference-in-differences method. This has been checked by looking at the treatment group averages of outcome variable for each datapoint prior to initiation of the policy and compared with that of the control group.

Data sources

Quarterly data on FDI flows, export and import of goods and services data has been obtained from CEIC database. FDI stock data has been obtained from Unctad. Quarterly data on nominal GDP has been obtained from the World Bank’s Global Economic Monitor. Data on governance indicators such as control of corruption, rule of law, regulatory quality, government effectiveness and voice and accountability has been obtained from the World Bank’s database on worldwide governance indicators. All data is quarterly and seasonally adjusted.

Results

Standard variables used to explain FDI inflows in the literature have the desired signs in our difference-in-differences regressions (see table A). FDI inflows tend to increase with higher GDP growth, higher trade-to-GDP ratio and higher FDI stock in a country. Governance variables like effectiveness of government policy, improvement in regulatory quality and increased accountability have a positive impact on inward FDI flows.

The difference-in-differences dummy (‘FDI screening dummy 1’) has the expected negative effect indicating the adverse impact of increased FDI screening on inward FDI flows beginning with the Covid period (Model 2). The coefficient is statistically significant with the addition of lagged FDI flows. In quantitative terms, the difference in expected FDI inflows in the treatment group before and after the intervention is 4.7% lower than the change in expected FDI inflows in countries without the intervention.

The impact of FDI screening dummy 2, which captures the selective policy intervention concentrated on some economies, also has the expected negative effect confirming the adverse impact of the policy uncertainty emanating from stricter evaluation of FDI applications on FDI inflows into the country. The magnitude of the coefficient is also higher and significant in case of selective policy intervention. The difference in expected FDI inflows in the treatment group before and after the intervention is 26.4% lower than the change in expected FDI inflows in countries without the intervention. However, with only few countries undertaking selective policy intervention, the control group contained too many countries, some of which were large recipients of FDI. To adjust for this bias, we adjusted for a country-type dummy (whether developed or emerging market economy). Post this adjustment, the average differential change in FDI inflows once the treatment group implemented the new FDI practices relative to the control group worked out to be (-)11.0%.

Conclusion

Policy uncertainty bears a significant impediment to foreign direct investment. Because of high sunk costs and limited information, investors often adopt a wait-and-watch approach before committing to FDI in an uncertain environment. This chapter highlights the effect of a recent policy change with respect to FDI where several jurisdictions across developed and emerging market economies increased scrutiny of FDI applications in their countries to avoid any opportunistic takeover of national assets by foreign corporates exacerbating uncertainty in the process. Our results confirm and substantiate that, in addition to variables like GDP growth, trade openness and institutional variables like regulatory quality, rule of law and accountability that were traditionally found to have a profound impact on FDI inflow, policy uncertainty also had a seminal effect on inward FDI. The chapter finds that increased vigilance and scrutiny of FDI proposals have an adverse effect on FDI inflows. The impact is higher and statistically significant during selective policy intervention.

Footnote

1. The countries with increased FDI screening intervention during 2020–22 were Australia, Austria, New Zealand, Canada, France, Germany, Hungary, India, Italy, Japan, Lithuania, Poland, Slovenia, Spain and the UK.

Bibliography

Asamoah, ME, Adjasi, CKD, and AL Alhassan, ‘Macroeconomic uncertainty, foreign direct investment and institutional quality: evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa’ in Economic Systems, 40 (4), pages 612–621, 2016.

Evenett, SJ, What caused the resurgence in FDI screening?, SUERF Policy Note, No 240, May 20, 2021.

Henderson, DJ, and S Sperlich, A complete framework for model-free difference-in differences-estimation, IZA Discussion Paper No 15799, Institute of Labor Economics, December 2022.

Jardet, C, Jude, C, and MD Chinn, Foreign direct investment under uncertainty: evidence from a large panel of countries, Working Paper No 29687, National Bureau of Economic Research, January 2022.

Julio, B, and Y Yook, ‘Policy uncertainty, irreversibility, and cross-border flows of capital’ in Journal of International Economics, 103 13–26, 2016.

Kurul, Z, ‘Nonlinear relationship between institutional factors and FDI flows: Dynamic panel threshold analysis’ in International Review of Economics & Finance, 48 pages 148–160, March 2017.

Lechner, M, ‘The estimation of causal effects by difference-in-difference methods’ in Foundations and Trends in Econometrics, Vol 4, No 3, pages 165–224, 2010.

Nguyen, CP, and GS Lee, ‘Uncertainty, financial development, and FDI inflows: global evidence’ in Economic Modelling, Vol 99, 105473, June 2021.

Schmidt, CW, and U Broll, ‘Real exchange-rate uncertainty and US foreign direct investment: an empirical analysis’ in Review of World Economics, Vol 145, No 3, pages 513–530, October 2009.

Solomon, B, and I Ruiz, ‘Political risk, macroeconomic uncertainty, and the patterns of foreign direct investment’ in The International Trade Journal, 26 (2), pages 181–198, April 2012.

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (Unctad), ‘The evolution of FDI screening mechanisms: key trends and features’ in Investment Policy Monitor, No 25, February 2023.

Worldwide Governance Indicators, 2024 Update, World Bank, http://www.govindicators.org/.

Note

Countries included in the sample: Australia; Austria; Belgium; Brazil; Canada; Chile; China; Colombia; Czech Republic; Denmark; Finland; France; Germany; Greece; Hungary; Iceland; India; Indonesia; Israel; Italy; Japan; Latvia; Lithuania; Mexico; Netherlands; New Zealand; Nigeria; Norway; Poland; Portugal; Russia; Slovakia; Slovenia; South Africa; South Korea; Spain; Turkey; Ukraine; UK.

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@centralbanking.com or view our subscription options here: www.centralbanking.com/subscriptions

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com