Trends in reserve management: 2025 survey results

Executive summary

Trends in reserve management: 2025 survey results

Fiscal divergence and its implications for reserve managers

Foreign direct investment inflows and FDI screening policies

Interview: Juliusz Jabłecki

Is the central bank gold rush over?

Market sentiment analysis in reserve management

Appendix 1: Survey questionnaire

Appendix 2: Survey responses and comments

Appendix 3: Reserve statistics

This annual survey of reserve managers was conducted by Central Banking Publications from January through to early March 2025. The survey, which is the 21st in the annual HSBC Reserve Management Trends series, was made possible by the support and co-operation of the reserve managers who take part in it. They contributed on the condition that neither their names nor those of their central banks would be mentioned in this report.

Summary of key findings

- US protectionist policies were the most significant risk that reserve managers said they would face in 2025. Of 88 central banks, 39 (44.3%) voted it their most pressing concern.

- Expecting higher levels than the pre-pandemic era, inflation and interest rates were far and away the most important factor that central bank officials said would affect their reserve management over the next five years.

- On average, reserve managers expected interest rate divergence between the US and the eurozone to exceed 175bp by the end of 2025.

- Ranking the performance of G7 bond markets and China, reserve managers’ confidence in the UK and Germany has rebounded in the last 12 months. China ranked poorly, just ahead of Japan. Reserve managers’ analysis taking FX into account shifts expected relative performance from purely a rates perspective, accounting for political and fiscal risks.

- Over two-thirds of central banks that incorporated geopolitical risks made changes to their reserve management in the last 12 months: 45 out of 62 (72.6%), up from 30 out of 56 (53.6%) last year. More than half (35, or 56.5%) considered changes this year. Deglobalisation, trade wars and supply chain realignment shift FX preferences and reserve diversification. Globally, the most common change was to issuers, followed by counterparties and currencies invested in.

- Just over half of central banks said they saw their FX and gold reserves increasing in 2025, to maintain investor confidence in the country and as a buffer for possible FX intervention. As global growth stalled, other dominant reasons included import cover requirements, servicing external debt and greater liquidity needs in uncertain markets.

- Another striking result was that half of 84 central banks said they had intervened in FX markets in the last 12 months. Central banks often do not publicly announce FX interventions – rendering them both at once a highly important and underreported tool. Removing eurozone central banks from analysis, the proportion of central banks that had intervened in FX markets in the last 12 months rose to 42 out of 69 central banks (60.9%).

- As inflation reared its head and geoeconomic risks abounded, half of reserve managers said they expected the pace of diversification to accelerate over the next 12 months (44, or 50.6%). Reserve managers also cited Brics countries’ (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) de-dollarisation policies and digital currencies as driving factors, particularly China’s digital yuan.

- Over the last 12 months, as the Fed’s higher-for-longer stance played out, close to half of reserve managers said they had increased their duration and liquidity. However, they discussed important nuances around investment strategies with regard to yield curve behaviour.

- This year, the survey also asked how reserve managers expected to position their portfolio over the next 12 months. Forty-three central banks said they intended to increase their asset class diversification (51.2%), and around one-third said they anticipated increasing liquidity and duration.

- Beyond the core reserve currencies, including the US dollar, euro, sterling and yen, a group of mid-sized western economies, or allies of the West, continued to receive investments from a wide set of central banks. This is particularly true of Australian and Canadian dollars. However, adding a question on the proportion of reserves invested this year reveals that allocations rarely rose above 3%.

- This year, fewer central banks said they invested in mainland China: 36 out of 83 central banks (43.4%), compared with 47 out of 84 (56.0%) in 2024. Chinese renminbi also emerged as the currency that the most central banks were considering investing in now, via onshore investments.

- In terms of stablecoins and cryptocurrencies, no central banks reported making investments. Meanwhile, interest in green bonds and social and sustainability bonds was growing. Nonetheless, the proportion of reserves invested in green bonds and social and sustainability bonds tends to be below 1% globally.

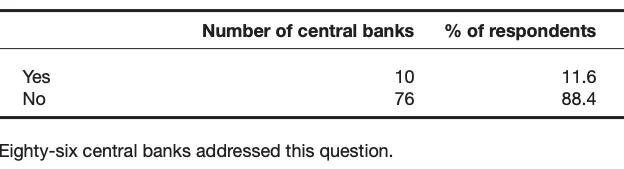

- Although no reserve managers said they were investing in cryptocurrencies, 10 (11.6%) said they thought cryptocurrencies were becoming more credible as an asset class. However, no central bank thought bitcoin should be considered a suitable asset class for reserves. Most central banks were against a strategic bitcoin reserve fund (50, or 59.5%), but a significant number (33, or 39.3%) were unsure.

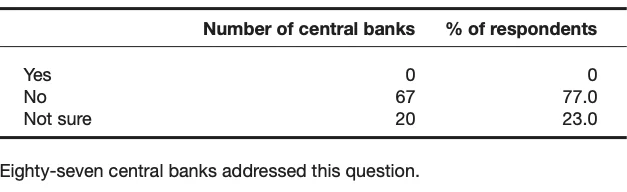

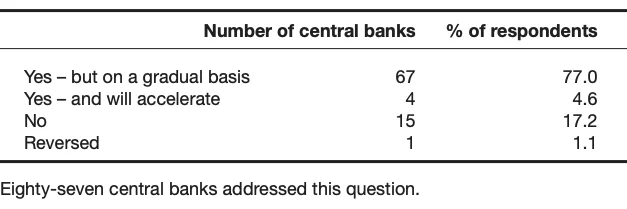

- As the global landscape had become more multipolar, most reserve managers thought de-dollarisation was increasing, but on a gradual basis (67, or 77.0%), and fewer reserve managers than last year thought de-dollarisation of global FX reserves was not increasing (15, or 17.2%). Reserve managers pointed to Brics countries actively exploring ways to reduce reliance on the US dollar and promote alternative currencies in international trade, as well as the continued alignment of China, Russia, Iran and North Korea.

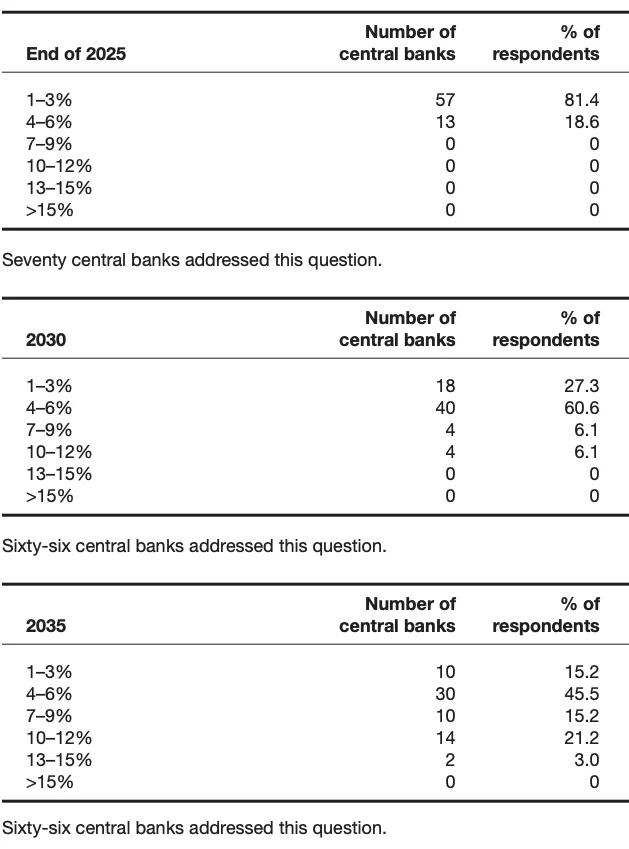

- Respondents for the most part expected renminbi reserves to remain at 1–3% by the end of this year (57, or 81.4%). This fell dramatically to 27.3% of respondents expecting renminbi in global reserves to remain at this level by 2030, and falls to just 15.2% by 2035. Nevertheless, the renminbi’s share of global reserves was still expected to remain between 1% and 15% at the end of 2035. Around half of central banks expected to be investing 1–6% of their reserves in renminbi in 10 years’ time.

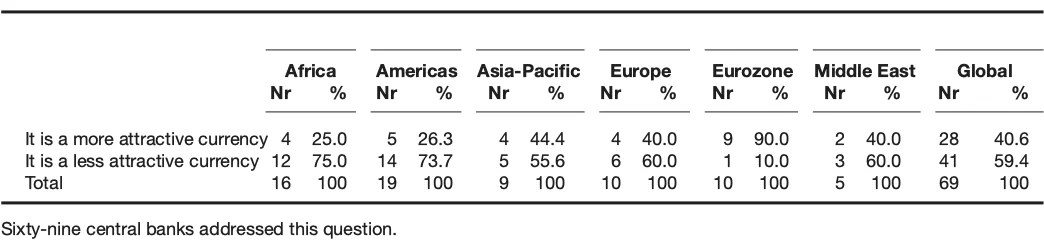

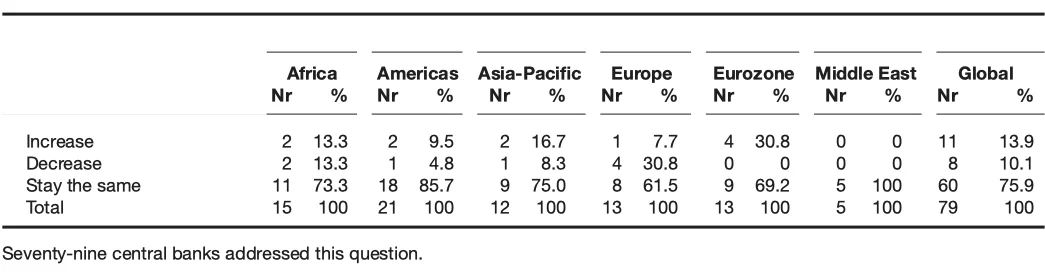

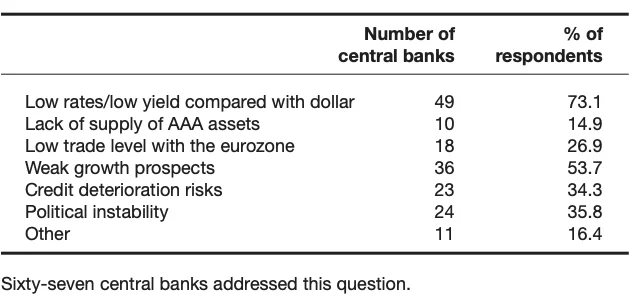

- Many more reserve managers came to view the euro as a less attractive currency over the past year. Of 69 reserve managers that answered this question, 41 (59.4%) said that the euro had become a less attractive currency. In contrast, of 67 central banks that responded to this question last year, 41 (61.2%) had said they thought the euro had become more appealing. Nonetheless, slightly more central banks globally were preparing to increase their investments in euros (11, or 13.9%), than decrease them (8, or 10.1%). Low rates/low yield compared with the dollar emerged as the main hurdle identified by central banks for investing in the euro (49, or 73.1%). Around half of respondents to this part of the question cited weak growth prospects.

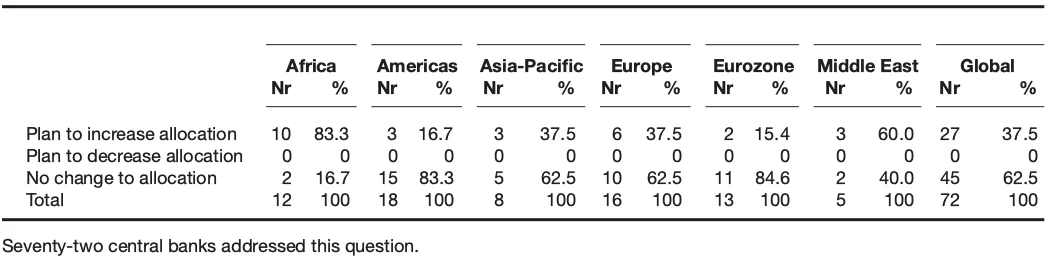

- Despite record-high gold prices, twenty-seven out of 72 central bank respondents to this question (37.5%) said they expected to increase their allocation to gold in the next year. Among the 27 central banks planning to increase their gold allocations, most saw it as a portfolio diversifier. Many also saw it as a long-term store of value, a good performer during times of crisis and a geopolitical diversifier.

- Ten (11.4%) central banks said they were actively using AI or machine to optimise their reserve management operations.

- Central banks have been moving to make socially responsible investing a priority. Sixteen (18.0%) said their prioritisation of SRI had increased over the previous 12 months. Fourteen central banks (35.9%) included sustainability as a fourth reserve management objective, although allocation in reserves remained very low.

Profile of respondents

The survey questionnaire was sent to 152 central banks in January 2025. By March, 91 central banks had sent their feedback. These institutions jointly manage over $7.1 trillion. This represents 62% of total allocated global reserves in the fourth quarter of 2024, according to the International Monetary Fund’s Currency composition of official foreign exchange reserves (Cofer) survey. The average reserve holding was $78.2 billion. Breakdowns of the respondents by geography, economic development and reserve holding can be found in the tables below. The term ‘eurozone’ refers to the group of 20 central banks whose national currency is the euro, as well as the European Central Bank (ECB). The term ‘Europe’ refers to all other central banks in the region.1

Which in your view are the most significant risks facing reserve managers in 2025? (Please rank the following 1–6, with 1 being most significant.)

US protectionist policies were the most significant risk that reserve managers said they would face in 2025. Of 88 respondents to this question, 39 (44.3%) voted it their most pressing concern. Even before the tariff announcements on April 2, reserve managers said the re-election of president Donald Trump and his commitment to ‘America first’ policies, such as trade tariffs, export controls and restrictions on foreign investments, was creating heightened volatility in financial markets, and expected it to have global ramifications on geopolitics and trade.

“US protectionist policies and volatile inflation pose major risks by impacting trade flows and reserve asset returns, while geopolitical tensions add uncertainty to asset security and liquidity management,” said a reserve manager of a central bank in the Americas.

A trade war, aside from affecting reserve portfolios, could trigger inflation and push economies into recession. This marks a shift from last year when geopolitical escalation was the most significant risk for reserve managers. Then, 31 out of 87 ranked geopolitical escalation in first place (35.6%). This year, only 17 of 89 (19.1%) did so, although it was the second-highest ranked. A reserve manager of a central bank in the Asia-Pacific region pointed to the challenges of balancing portfolios and adequately protecting the value and liquidity of reserves, against “the realities of an increasingly uncertain global landscape”.

Many central banks have now finished their hiking cycle, but Trump’s tariffs threaten the resurgence of inflation both in the US and abroad. Volatile inflation (17.0%), and global monetary policy and interest rate divergence (15.7%), followed closely behind geopolitical escalation as reserve managers’ next most significant concerns.

“Increased interest rate divergence, especially between the eurozone, which continues to cut rates successively, and the US, which is now indicating some restraints on its rate cut plan, may be a cause of concern to the effectiveness of co-ordinated monetary policy responses and global financial stability,” said a reserve manager of a central bank in Africa. This “may increase market volatility, especially in the FX [foreign exchange] space”.

Unsustainable fiscal deficits and depressed global growth were ranked lowest in terms of risks on a global level, although unsustainable fiscal deficits posed acute challenges for some jurisdictions and central banks. “Higher rates for longer would exacerbate the already elevated US fiscal deficit by increasing the debt service costs,” said a reserve manager of a central bank in the Americas. This is “particularly troubling, given that, in 2025, around 25% of the total debt is set to mature”, they added.

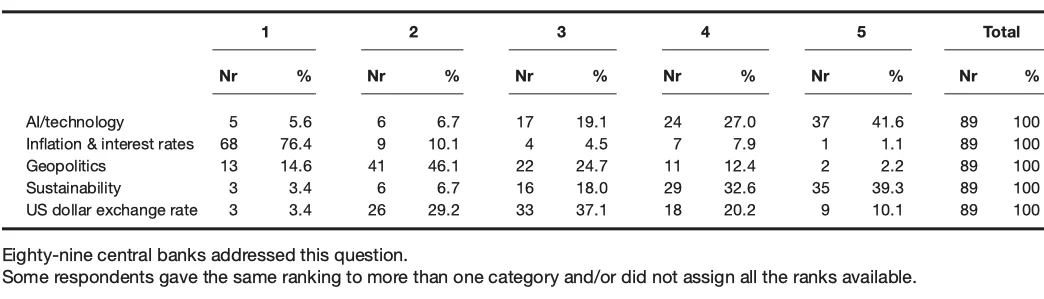

What do you think will be the most important factors affecting your reserve management over the next five years? (Please rank 1–5, with 1 being most important.)

Inflation and interest rates are far and away the most important factor that central bank officials said would affect their reserve management over the next five years. Of 89 respondents to this question, 68 (76.4%) ranked it highest. Higher rates make entry points in fixed income assets more attractive, but pose challenges for managing existing portfolios due to the price impact on duration assets. “Most of our holdings are in government debt focused on short to medium maturities. The risk from a returns perspective is focused on duration risks from volatility in rates,” said a reserve manager of a central bank in the Asia-Pacific region.

Geopolitics and the US dollar exchange rate came second (41, or 46.1%) and third (33, or 37.1%). This order holds when position rankings are added. “Geopolitics is right now the most decisive factor for reserve management. Commercial war, sanctions, tariffs are all geopolitical weapons,” said a reserve manager of a central bank in Africa.

The US dollar exchange rate was especially significant for portfolios with a dollar numeraire. “The US dollar will be the most important factor affecting our reserve management over the next five years, given its dominance in global trade and finance, along with its stability and performance,” said a reserve manager of a central bank in the Asia-Pacific region.

“Financial fragmentation may make EM [emerging market] economies more vulnerable to shocks, which will limit opportunities for reserves portfolios to diversify into these economies,” a reserve manager of another central bank in Africa agreed. “Long-term geopolitical tensions may impact the appetite for risk assets and exacerbate demand for safe-haven assets (USTs), which will make these more expensive.”

By mode, reserve managers viewed sustainability as more consequential than artificial intelligence in the medium term, although this order reverses when previous rankings are added. “Artificial intelligence and technology are becoming critical for optimising reserve management, while inflation, interest rates and USD movements will continue to shape asset allocation and risk management strategies,” said a reserve manager of a central bank in the Americas.

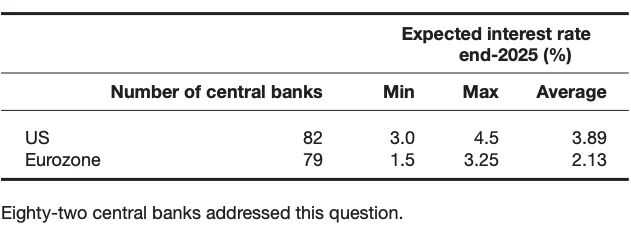

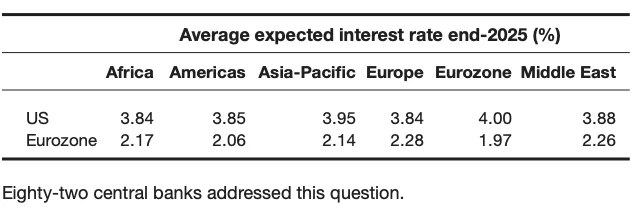

Where do you believe policy rates in the US and the eurozone will be at the end of 2025?

In terms of monetary policy divergence, globally, reserve managers’ minimum expectations of the US Federal Reserve’s rates at the end of 2025 were at the upper bound of the eurozone’s. Eighty-two reserve managers projected the Fed’s interest rates to be somewhere between 3.0% and 4.5% by the end of the year. In contrast, 79 reserve managers expected that the ECB would set interest rates somewhere between 1.5% and 3.25%. On average, reserve managers expected interest rate divergence between the US and the eurozone to just exceed 175 basis points, although this expands to 300bp taking only minimum and maximum projections into account.

By geography, only eurozone central banks expected the divergence between the US and eurozone to exceed 200bp. On average, reserve managers of central banks in the eurozone expected the Fed’s interest rate to be higher, and the ECB’s lower, than reserve managers in other regions. Meanwhile, close neighbours in Europe expected the narrowest interest rate divergence between the US and the eurozone, of just over 150bp. The term ‘Europe’ refers to central banks on the continent outside the eurozone.

How will this affect your reserve management decisions?

In a comments-based question, reserve managers described a bias towards US-denominated assets because of a higher-for-longer interest rate environment in the US. “In terms of currency diversification, the divergence in policy rates between the US and EU is one of the main factors driving the underweight position in euros,” said a reserve manager of a central bank in Africa.

Echoing a similar view, “our reserve management strategy will consider increasing exposure to USD-denominated assets to capitalise on higher yields”, a reserve manager of a central bank in Europe said. This central bank would consider “moderately” extending the duration of its fixed-income portfolio to lock in higher rates, “while maintaining diversified currency exposure to manage FX risks effectively”.

Although reserve managers expected the yield curve to normalise, uncertainty prevailed. “In the medium term, the plan is to add duration to the portfolio to lock in attractive yields and then benefit from yield curve normalising,” added the reserve manager from the central bank in Europe. Others also pointed to short-duration assets subject to reinvestment risk. Here, a reserve manager of a central bank in Africa proposed that spread strategies could be “attractive”. The view from a central bank in the Americas was that, “if the interest rate curve changes, it would be favourable to extend investments, otherwise, to maintain short-terms”. Offering an alternative view yet, a reserve manager of a central bank in the Americas said it will “aim to minimise portfolio volatility by maintaining exposure at the shorter end of the curve, where yields remain attractive while reducing duration risk in a potentially shifting rate environment”.

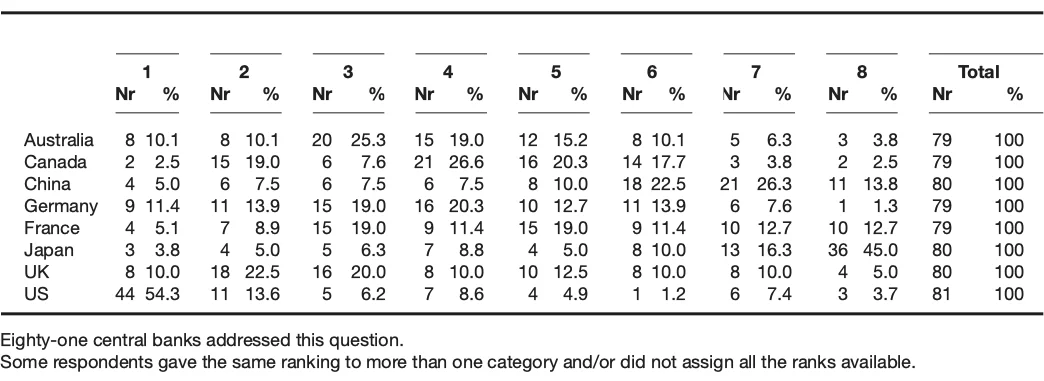

Which of the below countries’ bond markets do you think will see relative outperformance/underperformance? (Please rank in order 1–8 which market you feel will outperform the most, with 1 being the best-performing.)

Investor confidence in the UK and Germany seems to have rebounded in the last 12 months. Last year, reserve managers viewed the UK as both the second most attractive investment destination, as well as second least attractive, before Japan. This year, adding together first and second rankings puts the UK second and Germany third, raising Germany’s expected outperformance up from fifth place last year.

Similarly to last year, reserve managers were clear that they thought US bond markets would outperform relative to other Group of Seven countries in 2025–26. A majority ranked the US first (44, or 54.3%). Reserve managers were equally clear about Japan relatively underperforming: 36 (45.0%) ranked it last.

Adding votes in previous ranks together, Australia was fourth, Canada fifth and France sixth. This year, reserve managers were also asked about expectations around China’s performance. China ranked below France but above Japan, in seventh place.

Reserve managers gave a range of views, however, depending on expected economic performance, interest rates and FX.

In terms of monetary policy, central banks such as the ECB, Bank of Canada (BoC), Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) and Bank of England (BoE) were “expected to ease at a faster pace than the Fed and therefore their bond prices should appreciate”, said a reserve manager of a central bank in the Middle East. However, “risks to bond price appreciation in France, Germany and Canada will be political, while risks to that of the UK’s will be based on the fiscal deficit”, they added.

A reserve manager of a eurozone central bank agreed that accommodating monetary policy would lead to an increase in the price of bonds. They expected “China and European economies to underperform, leading to lower rates and therefore outperformance in bonds”. However, while a reserve manager of a central bank in Africa also pointed out that China’s bond market was “largely shielded from fiscal pressures due to high domestic savings and limited external borrowing”, and a “dovish PBoC [People’s Bank of China] means China’s bond yields have room to decline further, supporting price appreciation”, the dominant view among reserve managers was that China’s bond markets faced headwinds from policy uncertainty and slowing growth.

A reserve manager of a central bank in the Asia-Pacific region also countered: “European countries may underperform due to the lingering economic uncertainty, relatively high inflation risks and the potential volatility from geopolitical challenges”.

Offering an alternative view to Japan as the worst-performing market – being the only major economy where there were expectations of higher interest rates – a reserve manager of a central bank in the Americas said that “Japan’s bond market is expected to perform well due to yield curve control and stable demand”. It was their view that Australia and Germany also “remain attractive for their relative economic resilience”.

When FX was taken into account, assuming a USD numeraire, a reserve manager of a central bank in Africa said that “US exceptionalism is expected to remain undisputed under Trump 2.0”. Further, “tariff policy usually drives a stronger USD”, and reshoring was expected to be funded from divestment from emerging markets.

Are geopolitical risks incorporated in your risk management/asset allocation decision-making?

Another change from last year is data suggesting an increase in the number of reserve managers incorporating geopolitical risks into their reserve management. Of 87 respondents to the question, 66 central banks (75.9%) said they incorporated geopolitical risk into their risk management and asset allocation decision-making, up from 59 (67.0%) in 2024.

By geography, a higher share of central banks in Africa, the Asia-Pacific region, Europe and the eurozone said they incorporate geopolitical risks into their reserve management and asset allocation decision-making. Compared with last year’s survey, in Africa, the proportion rose from 66.7% to 100%, in Asia-Pacific from 77.8% to 86.7%, from 73.3% to 80.0% in Europe, and from 47.1% of eurozone central banks to 66.7% in 2025.

Reserve managers are assessing the risks from geoeconomic fragmentation in terms of US-China decoupling, sanctions and friendshoring effects on trade and reserve currency preferences. Deglobalisation, trade wars and supply chain realignment have shifted FX preferences and reserve diversification. In terms of geopolitical conflict and war, tensions in the Middle East and the South China Sea, and risks to energy security, can impact asset valuations.

“Reserve managers should assess the political stability of issuing countries, alongside traditional credit ratings,” said a reserve manager of a central bank in Africa. Incorporating stress-testing models that account for geopolitical shocks, such as a sudden regime change or international sanctions, was “critical”.

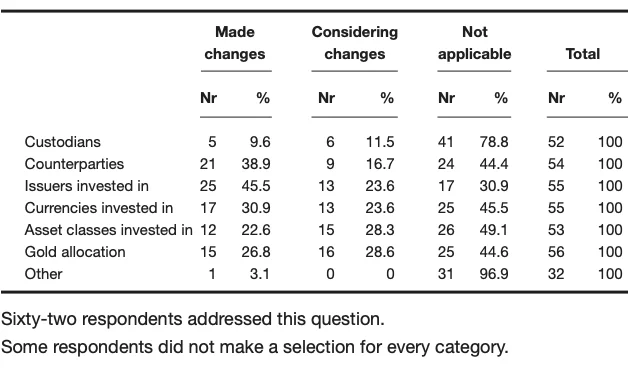

If yes, what changes have you made in the last 12 months?

A striking result was that over two-thirds of central banks that incorporated geopolitical risks into their reserve management made changes in the last 12 months: 45 out of 62 (72.6%), up from 30 out of 56 (53.6%) last year. More than half (35, or 56.5%) considered changes this year.

Globally, the most common change was to issuers (25, or 45.5%), followed by counterparties (21, or 38.9%) and currencies invested in (17, or 30.9%). A number of central banks made changes to their gold allocation (15, or 26.8%) and asset classes invested in (12, or 22.6%). A few changed their custodians (5, or 9.6%).

A further 16 central banks considered making changes to their gold allocation (28.6%), 15 to asset classes (28.3%), 13 to issuers and currencies (23.6%), nine to counterparties (16.7%) and six to custodians (11.5%).

Last year, many central banks in the Asia-Pacific region were first to move in light of geopolitical risks. This year, central banks in Africa were most likely to have made changes to counterparties, issuers, asset classes and currencies. This reflects results in 2024 that showed more reserve managers in Africa were considering making changes in 2024, relative to other regions.

Central banks in Europe were most likely to have made changes to their gold allocation as a result of geopolitical risks in the last 12 months. Next year may see changes in gold allocation among the relatively high number of central banks in Africa that have been considering changes, as reserve managers discuss domestic purchasing schemes.

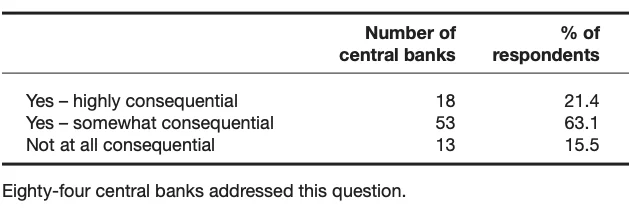

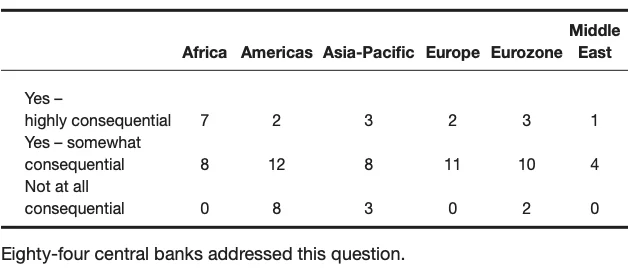

Is the ‘weaponisation’ of reserves, notably the seizure of Russia’s assets, consequential for the future of reserve management?

“This sets a highly problematic precedent, raising concerns about the security and neutrality of reserve assets,” said a reserve manager of a central bank in the Americas.

More than four in five reserve managers agreed that the weaponisation of reserves was consequential for reserve management. Three in five saw it as “somewhat consequential” – and one in five said it was “highly consequential”.

“It is definitely consequential,” a reserve manager of a central bank in Africa underscored: “It removes the notion of the sovereignty of reserve management operations, and geopolitical analysis has become increasingly important.”

Central banks in Africa deemed the weaponisation of reserves most significant, among peers globally. “The worry is that central bank assets could be sanctioned, seized or tapped if geopolitical conflicts escalate or if their country has any fallout with the superpowers,” said a reserve manager in the region. “This undermines the status of FX reserves as a country’s most liquid and secure store of wealth.”

“Reserve managers have to review the risk of sanctions when making investment decisions,” another reserve manager of a central bank in Africa added. “Emerging countries will now think twice before allocating their reserves regionally, in terms of currency and type of assets,” said a third.

However, currently, the dollar was “very entrenched”, making it “costly” for anyone to operate without it, a reserve manager of a central bank in the Americas said. Another reserve manager of a central bank in the region acknowledged “that events such as the seizure of Russia’s assets will provide a degree of motivation for some central banks to seek or develop alternative reserve management currencies”. However, “the safety, transparency and liquidity of US dollar debt markets places a practical limitation on the adoption of alternatives at scale”.

Nonetheless, the weaponisation of reserves “enforces the existing, slow trend of de-dollarisation”, said a reserve manager of a eurozone central bank. “In a more fragmented world, investments will likely be more skewed towards those more geopolitically aligned,” added another reserve manager of a eurozone central bank.

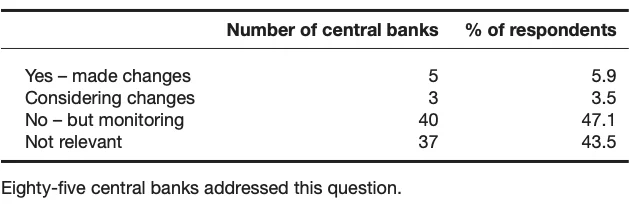

Has this affected your own reserve management?

As a result of the weaponisation of reserves, a few central banks considered making changes (3, or 3.5%) and slightly more made changes (5, 5.9%). Of the 85 respondents to this question, around half said they had not made changes, but were “monitoring” developments.

Of the central banks that had made changes, one was in Africa, two in the Asia-Pacific region, one in Europe and one in the eurozone. A central bank in the Middle East and two in Africa were considering making changes.

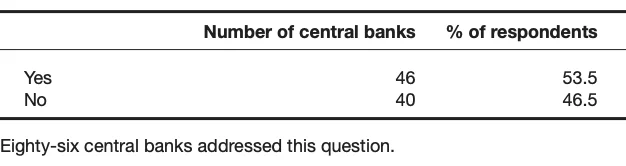

Do you see your FX and gold reserves increasing in 2025?

Just over half of central banks said they saw their FX and gold reserves increasing in 2025. Of the 86 respondents to this question, 46 (53.5%) said their objective this year was to build their reserves.

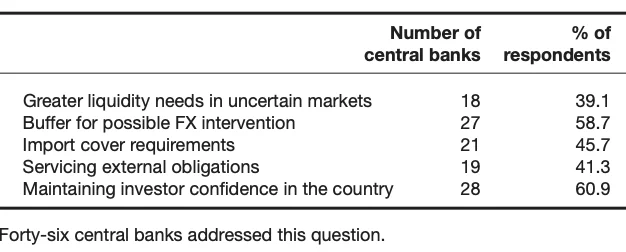

If yes, what would be the reasons? (Please tick all that apply.)

International reserves can be essential for effective monetary policy and financial stability.

Maintaining investor confidence in the country (28, or 60.9%) and reserves acting as a buffer for possible FX intervention (27, or 58.7%) were the most common reasons why central banks were aiming to increase their reserves in 2025. As global growth stalls, around half of the 46 reserve managers that answered this part of the question said they were planning to increase their gold and FX reserves due to import cover requirements, and around 40% said servicing external debt and greater liquidity needs in uncertain markets.

Reserve managers highlighted how national security factors can pose acute challenges for reserve managers. “Our FX reserves have been on a downward trend for some time now, as receipts from the energy sector have declined substantially while we continue to uphold FX interventions,” said a reserve manager of a central bank in the Americas. “Given the growing domestic demand for imported goods, we do not foresee any meaningful growth in our reserves in the near term.”

Another reserve manager in the region said: “The lack of economic activity due to the security situation in [the jurisdiction] has limited imports and, in turn, reduced immediate pressure on USD demand. However, when conditions improve and activity picks up, we anticipate renewed pressure on the FX rate.”

In contrast, a reserve manager of a central bank in Africa highlighted how improved fiscal policy has raised expected reserve levels “mainly as a result of improved government revenue and lower spending”.

In the eurozone, a reserve manager said the central bank planned to further increase the level of its reserves to improve the return/risk ratio: “The expected return of our reserves is higher than our cost of funding.”

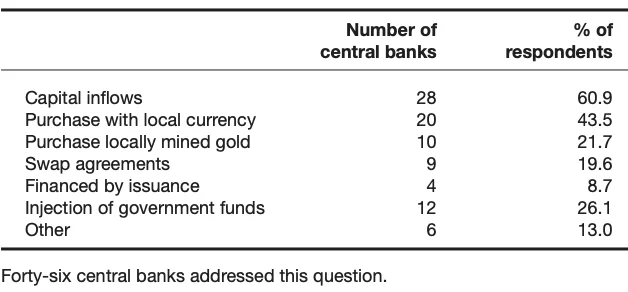

If yes, how do you intend to increase reserves? (Please tick all that apply.)

Central banks said they planned to increase their FX reserves via capital inflows (28, or 60.9%) and purchases with local currency (20, or 43.5%). Around one-quarter said they intended to increase their FX and gold reserves via an injection of government funds, and around 20% by purchasing locally mined gold or swap agreements. Four (8.7%) said they intended to finance their reserves through issuance.

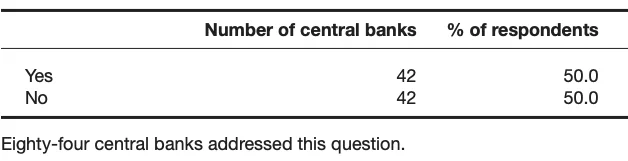

Have you intervened in FX markets in the last 12 months?

Another striking result was that half of 84 central banks said they had intervened in FX markets in the last 12 months. Central banks often do not publicly announce FX interventions – rendering them both at once a highly important and underreported tool.

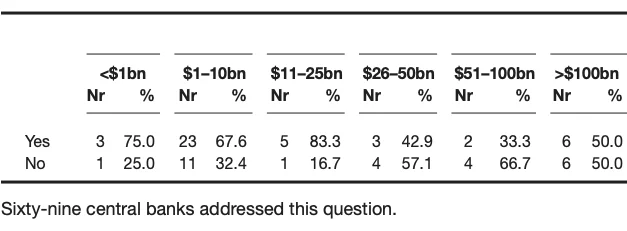

Removing eurozone central banks from analysis, the proportion of central banks that intervened in FX markets in the last 12 months rises to 42 out of 69 central banks (60.9%). This result supports the earlier finding that many central banks intended to increase their FX reserves for possible FX interventions in 2025.

By region, central banks in Africa were most likely to have intervened in FX markets over the last 12 months (13, or 86.7%), followed by central banks in the Asia-Pacific region (10, or 76.9%). Nonetheless, around 40–50% of central banks in the Middle East, Europe and the Americas also reported conducting FX interventions.

Central banks with reserves between $11 billion and $25 billion were most likely to have intervened in the last 12 months (5, or 83.3%), followed by smaller central banks with less than $1 billion (3, or 75.0%). Nonetheless, even among central banks with some of the largest reserves in the world, 50% (6) of respondents with over $100 billion in reserves intervened.

“Interventions were mostly done in the last two months of 2024,” said a reserve manager of a central bank in the Americas. “Internal FX volatility and local currency depreciation were among the factors related to the interventions.” This coincides with Trump’s election in November and yield curve inversion ending in December 2024.

“The [central bank] participates in the spot market to limit excessive [currency] volatility, whether it is appreciating or depreciating,” said a reserve manager of a central bank in the Asia-Pacific region. Describing a difficult balance, “the main purpose of exchange rate intervention was to implement one of the central bank’s objectives, which is exchange rate stability”, a reserve manager of a central bank in Europe explained, “but without violating the free-floating exchange rate regime”.

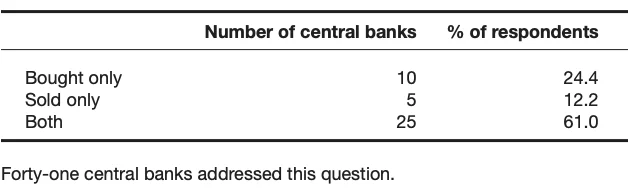

If yes, have you sold or bought local currency?

Most of the 41 central banks that intervened in FX markets in the last 12 months and answered this part of the question both bought and sold local currency (25, or 61.0%).

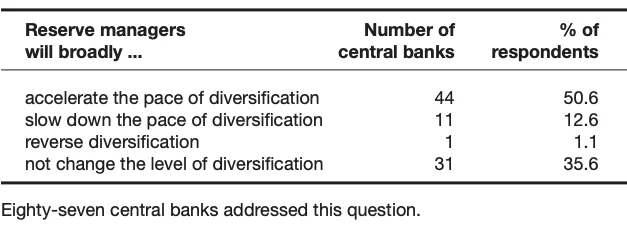

Regarding diversification, do you anticipate that over the next year reserve managers broadly will accelerate, slow down or not change the pace of diversification?

“I think that [the global financial crisis], zero interest rates, Covid and [the] sharp jump [in] inflation accelerated diversification already,” said a reserve manager of a central bank in Europe. As a result, between now and the end of the year, they “would expect implementation steps only”. Nonetheless, as inflation reared its head and geoeconomic risks abounded, half of reserve managers said they expected the pace of diversification to accelerate over the next 12 months (44, or 50.6%).

Diversification would be “driven by Brics’ de-dollarisation policies”, according to a reserve manager of a central bank in the Americas. “There is also a rise in digital currencies, which may prompt reserve managers to explore digital assets to diversify their investment portfolios,” a reserve manager of a central bank in the Asia-Pacific region added.

In agreement, in an “increasingly volatile” geopolitical and economic environment, reserve managers were rethinking “traditional” asset allocation strategies, a reserve manager of a central bank in Africa said: “Reserve managers are exploring ways to integrate digital assets into their portfolios.” Central bank digital currencies “may become more integral to the diversification process, especially in regions like Asia, where China’s digital yuan is gaining traction”, they added.

In contrast, “geopolitical risks surrounding US foreign policy, sanctions and the war in Ukraine will alter investor behaviour to a more cautious one, tilted to a more extensive use of safe-haven assets”, said a reserve manager of a central bank in Europe.

A reserve manager of a central bank in Africa said: “US, Japan, Germany and Canada are safe-haven assets, and their performance will be fuelled by the uncertainty from the shift in US trade and foreign policies.” Australia’s economic indicators, they added, seemed to put it “ahead of the curve with their inflation stabilising close to target”, labour remaining relatively strong, as well as their “energy production drive”.

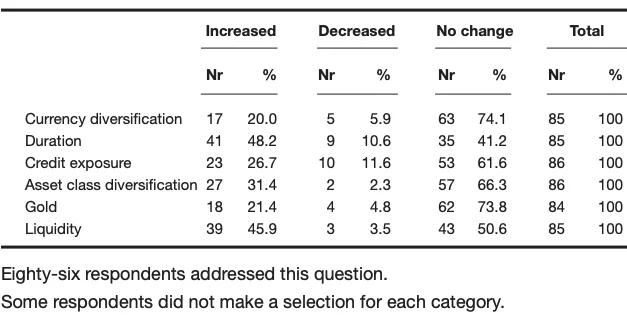

In the last 12 months, how did you position your reserve portfolio?

Over the last 12 months, as the Fed’s higher-for-longer stance played out, close to half of reserve managers said they increased their duration (41, or 48.2%) and increased their liquidity (39, or 45.9%). However, there were some important nuances around investment strategies with regard to yield curve behaviour.

“At the beginning of the year, we tactically reduced duration in our portfolios, taking advantage of the inverted yield curve,” said a reserve manager of a central bank in the Americas. “Nevertheless, some months later, we tactically increased duration in our portfolios, taking advantage of the rally of the bonds before the first cut of the federal funds rate.”

A reserve manager in Europe said that, in the rising yield environment, over the course of the past year, the central bank had maintained high liquidity by keeping a lower-duration profile. More recently, given monetary policy normalisation, the central bank had shifted liquidity into bond investments.

A reserve manager at another central bank in Europe said diversification into non-traditional became too expensive: “We have increased our exposure towards equities that act as a reserves diversifier and enhance returns over a long-term horizon. At the same time, we decided to unwind small positions in non-traditional currencies, as their overall diversification benefits were limited and did not justify the operating costs incurred.”

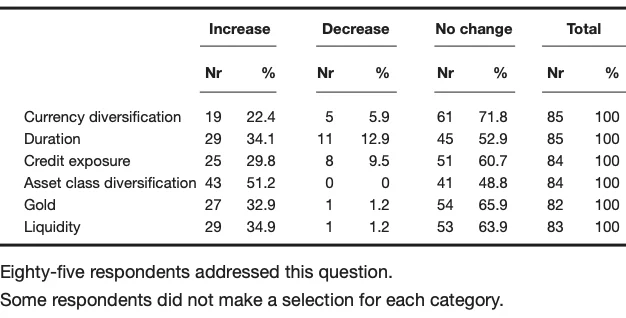

In the next 12 months, how do you anticipate positioning your reserve portfolio?

This year, the survey also asked what reserve managers expected to do over the next 12 months. Forty-three central banks said they intended to increase their asset class diversification (51.2%), and around one-third said they anticipated increasing liquidity (29, 34.9%) and duration (29, 34.1%). Percentages differ because not all reserve managers answered every part of the question.

“In case the USD depreciates significantly, we’d diversify a certain share of the FX reserves in USD,” said a reserve manager of a central bank in Europe. Additionally, if there is a decrease in yields, the central bank would “decrease the duration of the portfolios as well”.

A reserve manager of a central bank in Africa said they intended to “increase duration in the portfolio, albeit very cautiously, as the US may face reflationary pressures amid a global trade war and supply chain disruptions”. With regard to credit, “spread has compressed significantly over the last 10+ years”, particularly after the Fed’s rate tightening cycle, “which propelled demand for high-quality credit”. Therefore, they expected US dollar investment-grade excess returns to be “weaker when spreads are tight”. Instead, the central bank would “continue to diversify into quality” through supranational, sovereigns and agencies.

“We may increase our exposure to the covered and corporate bonds market in 2025,” added a reserve manager of a central bank in the eurozone. Another said that they planned to execute “temporary tactical deviations” without significant changes to their strategic asset allocation (SAA).

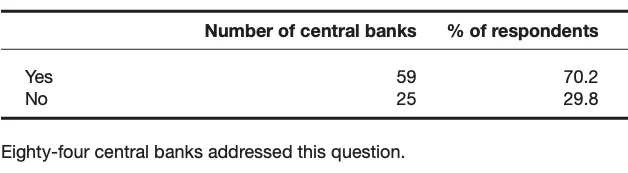

In your SAA and risk management process, do you incorporate correlation risk?

Most central banks said they incorporated correlation risk into their SAA and risk management process. Of the 84 reserve managers that answered this question, 59 (70.2%) answered in the affirmative. Nonetheless, 29.8% said they do not incorporate correlation risk.

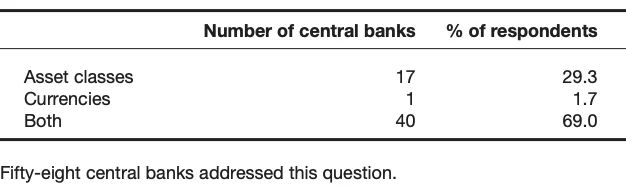

If yes, do you assess currencies, asset classes or both?

Of the central banks that do incorporate correlation risk, most 40 (69.0%) said they analysed both currencies and asset classes. Otherwise, central banks tended to assess asset classes only (17, or 29.3%), rather than currencies (1, or 1.7%).

A reserve manager of a central bank in the Asia-Pacific region said: “Correlations of asset classes and currencies are included in market risk management and SAA. However, actively changing correlations to observe possible effects and analyse correlation risk is not conducted.”

“Incorporating correlation risk into the SAA process allows the central bank to build more resilient portfolios that are better able to withstand market volatility, economic shocks and geopolitical risks,” a reserve manager of a central bank in Africa said, and “is crucial for optimising the risk-return profile”.

Elaborating on how their reserve department incorporated correlation risk, the reserve manager said the central bank analysed historical correlations through correlation matrices, “particularly during periods of heightened geopolitical risk or financial crises”. The central bank also used stress-testing or scenario analysis to simulate extreme market conditions to assess how correlations between asset classes and currencies shifted, to pre-emptively help adjust the portfolio. “Recognising how correlations shift in response to global events and market dynamics is key to enhancing portfolio performance and managing overall risk in a rapidly changing environment.”

While recognising that maximising risk-adjusted returns was an important part of the SAA process, other reserve managers stressed they prioritised asset-liability matching. Put simply, one reserve manager of a central bank in the Americas said: “Our currency exposure is determined by external debt.”

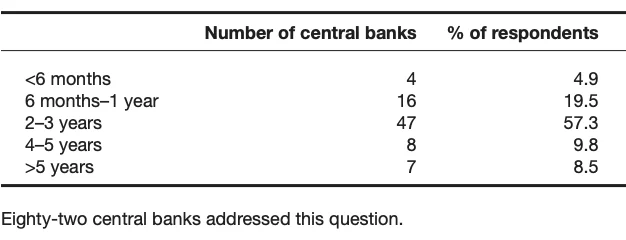

What is the duration of your fixed income portfolio? (Please round to the nearest year.)

The duration of most central banks’ fixed income portfolio ranged between two to three years (47, or 57.3%). Eighty-two reserve managers answered this question. Around one-fifth said duration was between six months and one year. Fewer had durations of four to five years (8, or 9.8%) or higher (7, or 8.5%). A minority had a duration of less than six months (4, or 4.9%).

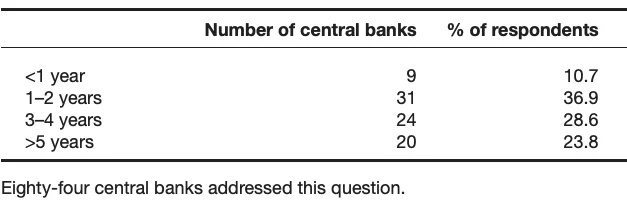

What is the investment horizon of your portfolio? (Please round to the nearest year.)

The investment horizon of central banks was more spread than duration. Although a small majority had an investment horizon of around one to two years (31, 36.9%), many also had a longer horizon of three to four years (28.6%) or five years or more (23.8%). Just over 10% of central banks said they had an investment horizon of less than a year.

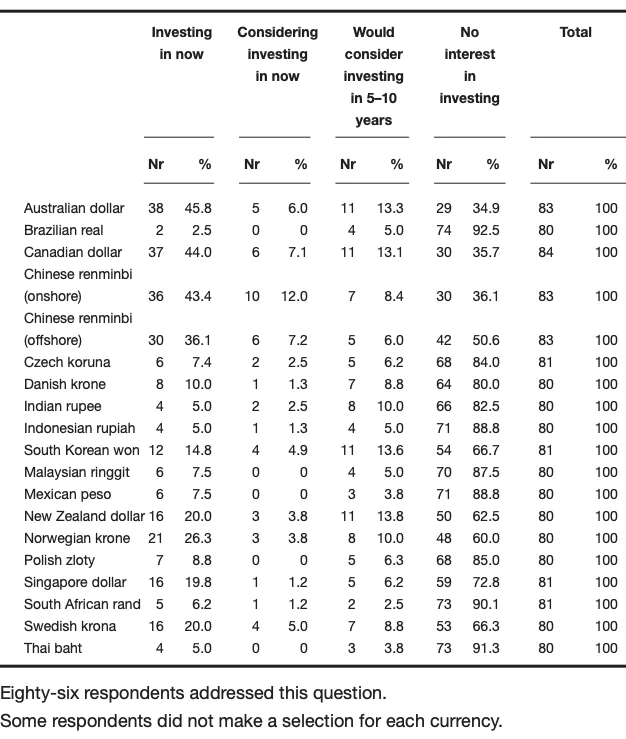

Which view best describes your attitude to the following currencies?

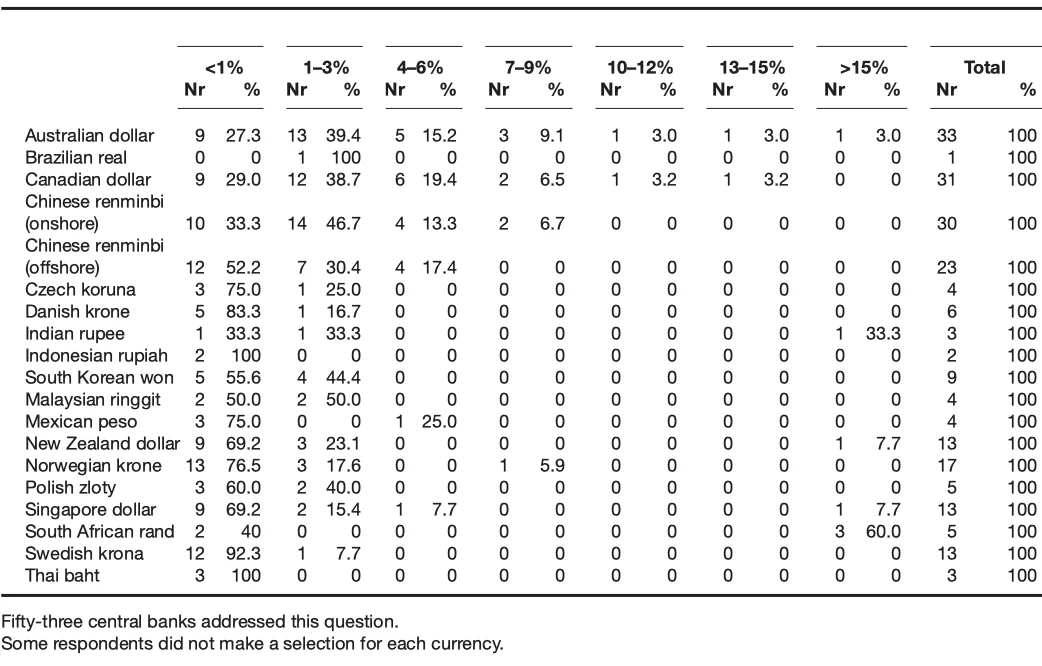

If investing in, what proportion of your reserves are allocated?

Beyond the core reserve currencies, including the US dollar, euro, sterling and yen, a group of mid-sized western economies, or allies of the West, continued to receive investments from a wide set of central banks. This is particularly true of Australian and Canadian dollars. However, adding a question on the proportion of reserves invested this year reveals that allocation rarely rose above 3%.

This year, fewer central banks said they were investing in mainland China: 36 out of 83 central banks (43.4%), compared with 47 out of 84 (56.0%) in 2024. Thirty central banks said they were making offshore renminbi investments (36.1%), level with last year.

Notably, renminbi holdings had been steadily growing until Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, but fell from 2.8% to 2.1% of global allocated FX reserves, as of Q2 2024, according to IMF data. Meanwhile, global FX reserves holdings in the Australian dollar and the Canadian dollar last year for a while overtook the renminbi for the first time.

At the same time, there were indications that while interest rates remained elevated, central banks had been moving their investments away from non-traditional reserve currencies into the dollar. Eighty-three central banks gave their view of the Australian dollar, and just 38 (45.8%) said they were investing in it, compared with 46 (53.5%) last year. Similarly, 37 central banks out of 84 (44.0%) this year said that they are investing in the Canadian dollar, compared with 42 out of 86 central banks (48.8%) in 2024.

Nevertheless, the Chinese renminbi emerged as the currency that the most central banks were considering investing in, via onshore investments (10, or 12.0%), followed by offshore investments in the renminbi (6, or 7.2%) and the Canadian dollar (6, or 7.1%).

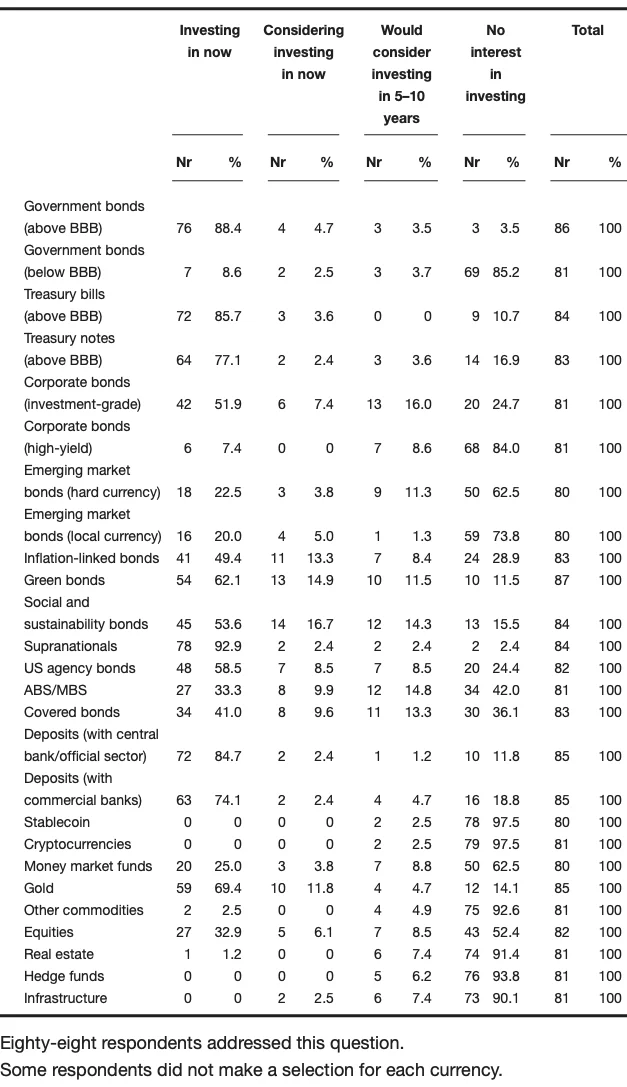

Which best describes your attitude to the following asset classes?

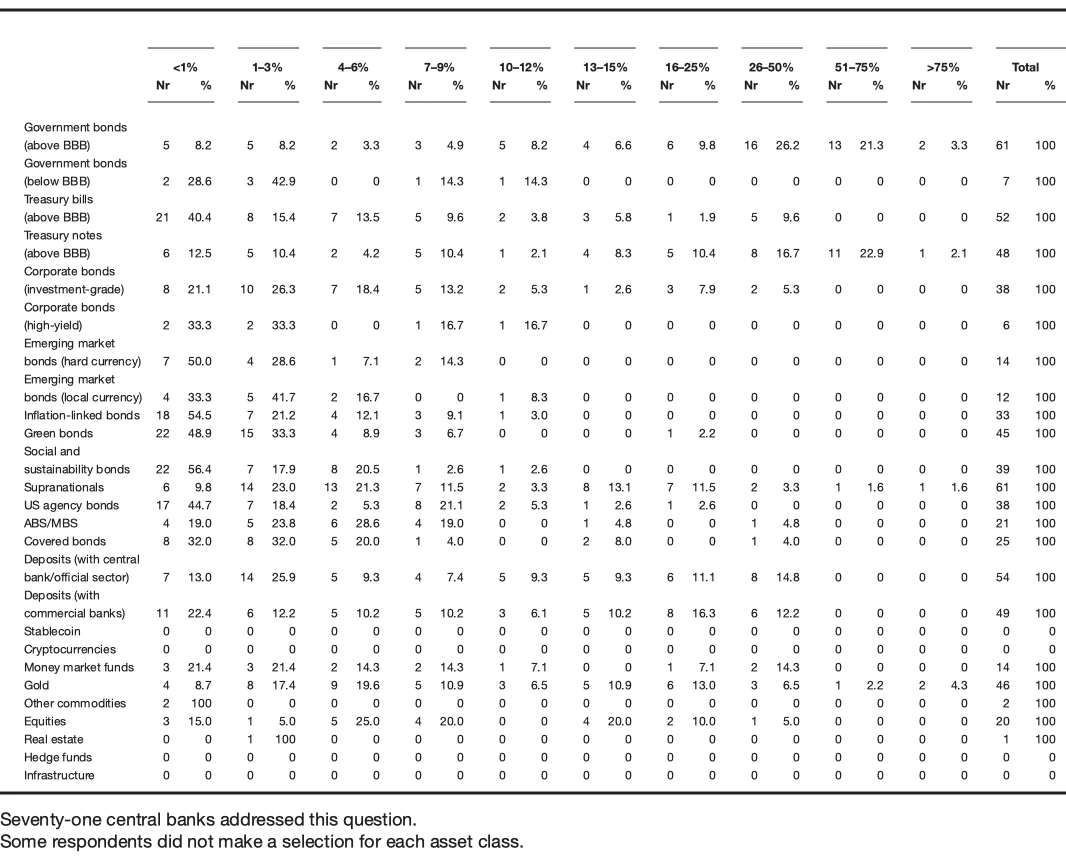

If investing in, what proportion of your reserves are allocated?

Supranationals (78, or 92.9%), government bonds with an above-BBB credit rating (76, or 88.4%) and Treasury bills with an above-BBB rating (72, or 85.7%) were leaders in terms of asset classes that central banks invested in. Many central banks also continued to invest in deposits with central banks and the official sector (72, or 84.7%), deposits with commercial banks (63, or 74.1%) and gold (59, or 69.4%). There appeared to be a shift, however, out of US agency bonds. Forty-eight central banks (58.5%) said they were investing in the asset class this year compared with 59 (70.2%) last year.

In terms of stablecoins and cryptocurrencies, no central banks reported having made any investments.

Meanwhile, interest in green bonds and social and sustainability bonds was growing. Fewer central banks this year, 10 out of 87 (11.5%), said they had no interest in investing in green bonds, with the majority of reserve managers either already investing in them (54, or 62.1%) or considering allocating reserves in the asset class (13, or 14.9%). Fewer respondents – 13 out of 84 central banks (15.5%) – than last year said they have no interest in investing in social and sustainability bonds. Nonetheless, the proportion of reserves invested in green bonds and social and sustainability bonds tended to be extremely low: below 1%.

Interest in inflation-linked bonds remained relatively stable year on year. In last year’s survey, 39 (44.8%) said they were holding inflation-linked bond investments, and 10 (11.5%) central banks said they were considering making an investment. This year, 41 (49.4%) central banks said they were investing in inflation-linked bonds, and 11 (13.3%) said they were considering making an investment imminently.

Are cryptocurrencies becoming more credible as an asset class?

Although no reserve managers said they were investing in cryptocurrencies, 10 (11.6%) said they thought cryptocurrencies were becoming more credible as an asset class. These were “assets related to illegal activities”, a reserve manager of a central bank in the Americas simply said.

Do you think bitcoin should be considered as a suitable asset class for reserve managers?

No central banks thought that bitcoin should be considered a suitable asset class for reserves. But, perhaps surprisingly, 20 (23.0%) reserve managers said they were unsure.

Many reserve managers pointed to the volatility of bitcoin, and cryptocurrencies more generally, making them unsuitable as an asset class. “They are incompatible with the traditional objectives of safety, liquidity and return,” said a reserve manager of a central bank in the Americas. “Their value can be highly volatile, and they still face an uncertain regulatory environment”, which is incompatible with the low risk tolerance profile of central banks. Although crypto assets could be used to generate returns, “the risks from fraud and other vulnerabilities are still elevated, demanding further regulation”. Crypto assets are also yet to become widely accepted mediums of exchange and stores of value. Reserve managers expressed that the liquidity and depth of crypto asset markets would need to improve, and the cost to trade those assets would need to decrease, before they could invest. “Robust” custody and safekeeping solutions would also need to be developed.

A reserve manager of a central bank in Europe said that, while bitcoin had a market and a price, its properties included “unknown reasons for price changes” and a specific form of credit risk stemming from potential hacks and monopolisation.

“That being said”, a reserve manager of a central bank in Africa added, “bitcoin could serve as a diversification tool” for large reserve managers with excess returns. “In certain market conditions, it may act as a hedge against inflation or currency devaluation.”

Countering this view, “central banks are more focused on central bank digital currencies”, said a reserve manager of a central bank in the Asia-Pacific region.

How do you view strategic bitcoin reserve fund proposals?

Similarly, although most central banks were against a strategic bitcoin reserve fund (50, or 59.5%), a significant number (33, or 39.3%) were unsure.

Do you think de-dollarisation of global FX reserves is increasing?

Most reserve managers thought de-dollarisation was increasing, but on a gradual basis (67, or 77.0%), up a smidge from 64 (75.3%) last year. Slightly more reserve managers than last year thought that de-dollarisation would accelerate (4, or 4.6%) and fewer reserve managers than last year thought de-dollarisation of global FX reserves was not increasing (15, or 17.2%).

The global economic landscape has become more multipolar, with the rise of emerging economies. India and Russia have agreed to trade in rupees and rubles, while China and Brazil have also signed deals to use the yuan and real for trade.

“These countries are seeking to reduce their reliance on the US dollar to assert greater economic independence and reduce vulnerability to US policies or sanctions,” said a reserve manager of a central bank in Africa. The ‘debasement’ trade was “here to stay”, they added, which can refer to strategies stemming from weakened currencies, against a backdrop of inflation and heightened geopolitical uncertainty since 2022. Aside from Brics countries, there was also greater regionalisation and strengthening ties within trading blocs, “including [the] continued alignment of the Crink countries”, they added. However, the role of the US dollar was supported by a strong economy, developed payment system, mature financial markets and a stable financial system – “it would be really hard for other financial markets to achieve such a level of development over the next couple of years”, said a reserve manager of a central bank in Europe.

Other reserve managers reiterated that, while they believed diversification away from the dollar was a growing trend in the medium to long term, in the short term, US exceptionalism in economic activity and the divergence in interest rates would favour the US dollar. Echoing this sentiment, “good returns in USD [have] slowed down the process, but it is still occurring”, said a reserve manager of a central bank in the Americas.

Are you considering changing your allocation to US dollar investments over the next 12 months?

Of the 86 central banks that revealed as to whether or not they are considering changing their dollar investments over the next 12 months, most did not anticipate making changes (64, or 74.4%). In fact, slightly more central banks expected to increase their dollar investments (14, or 16.3%) than decrease them (8, or 9.3%).

“The outlook suggests that USD-denominated assets are expected to deliver higher risk-adjusted returns compared to other traditional reserve assets, driven by relatively stronger growth and the Fed’s higher-for-longer monetary policy stance,” said a reserve manager of a central bank in Africa.

Five central banks in Africa, four in the Asia-Pacific region, four in Europe and one in the eurozone were planning to increase their dollar investments. Three central banks in the Americas, two in Asia-Pacific, two in Europe and one in the eurozone were planning to decrease their dollar investments.

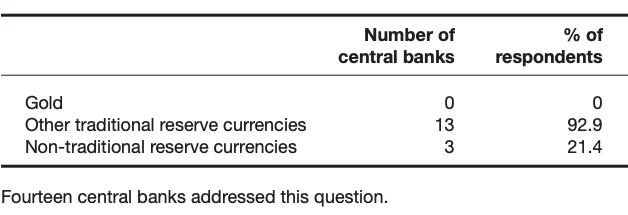

If increasing, what is this at the expense of? (Please tick all that apply.)

Central banks increasing their investments in the dollar overwhelmingly said this was at the expense of other traditional reserve currencies. The expected interest rate divergence between the US and the eurozone reported earlier suggests that this may at least in part be at the expense of the euro, although the return of investment in non-traditional currencies due to associated costs has also been called into question.

If decreasing, what is this to the benefit of? (Please tick all that apply.)

At the same time, central banks decreasing their dollar investments were most likely to invest in other traditional reserve currencies. Later, a reserve manager pointed out that the euro could look attractive now if your point of reference was the negative yield environment. A few central banks were planning to move out of the dollar to invest in non-traditional reserve currencies and a couple in gold.

What percentage of global reserves do you think will be invested in the renminbi by the end of 2025, 2030 and 2035?

Similarly to last year, most reserve managers thought that the renminbi’s share of global reserves would continue to rise throughout the decade. While no central banks expected the renminbi’s share to reach 10% or higher by the end of 2025, four central banks (6.1% of 66 respondents) thought it might do so by 2030. Sixteen central banks (24.2%) expected the renminbi’s share of global reserves to reach 10% or more by 2035.

Respondents for the most part expected renminbi reserves to remain between 1–3% by the end of this year (57, or 81.4%). This fell dramatically to 27.3% of respondents expecting renminbi in global reserves to remain at this level by 2030, and down to just 15.2% by 2035.

Nevertheless, the renminbi’s share of global reserves was still expected to be 1–15% at the end of 2035, according to the 66 respondents to this part of the question.

“The renminbi’s share of global reserves is expected to grow steadily due to China’s increasing integration into the global financial system and its role in regional trade agreements,” said a reserve manager of a central bank in the Americas. “Renminbi may be one of the beneficiaries of the de-dollarisation trend,” a reserve manager of a central bank in the eurozone added.

However, renminbi adoption in global reserves remained constrained by capital controls and liquidity concerns. “Greater acceptance of the renminbi in central bank reserves will depend on continued reforms in China’s financial markets and geopolitical dynamics,” added the reserve manager of a central bank in the Americas, as well as diversification benefits and operational ease.

A reserve manager of a central bank in Africa said: “China’s ongoing economic expansion and its rising share of global GDP, coupled with significant financial market reforms aimed at enhancing openness, transparency and liquidity, are expected to further strengthen its global economic influence.”

Offering an alternative perspective, “certainly, the renminbi has made some progress as an international currency”, a reserve manager of a central bank in the Americas said, “but its relevance continues to be limited and not proportional to the size and weight of the Chinese economy”. Further, “the share of global foreign exchange reserves held in renminbi-denominated assets has kept constant at about 2%, and since the Covid-19 pandemic, the Chinese economy has been struggling”, they added.

“Deteriorated macroeconomic conditions in China may discourage central banks from further diversification towards [the] renminbi,” agreed a reserve manager of a central bank in Europe. Indeed, based on the recent outlook, “we downsized our estimates”, a reserve manager of a central bank in the Middle East said. However, “although recently investors have been decreasing their RMB holdings, we believe that, in the long run, the share of RMB will continue to increase”, they added.

A reserve manager at another central bank in the eurozone said, however: “Other currencies might see an increase in their shares, such as EUR, GBP, JPY, SEK and NOK.”

What percentage of your reserves do you plan to invest in renminbi by the end of 2025, 2030 and 2035?

Around half of central banks expected to be investing 1–6% of their reserves in renminbi in 10 years’ time (48.5%).

Notably, 19 more central banks answered this question this year than in 2024, revealing something of a schism between central banks that foresaw investing in renminbi, albeit gradually, and those who did not see themselves investing at all, even by 2035.

“We have trimmed down our allocation to renminbi due to the yield differential between USTs and its Chinese counterparts, as well as persistent dollar strength,” said a reserve manager of a central bank in Africa. “We are also wary of China’s credit outlook, especially with the ongoing trade war rhetoric and continued impact on growth, which has remained persistently lower in the medium term.” Over the long term, if global interest rates and global growth normalised, the central bank might consider increasing its exposure to Chinese government bonds and policy bank bonds.

“We hold CNY for diversification purposes as well as a consequence of the swap lines with China,” a reserve manager said. However, currency allocation at the central bank depended on an asset-liability matching principle. “[Therefore,] we think that the share of CNY in our reserves will stay limited unless there is a significant increase in our swap lines with China.”

A reserve manager of a central bank in Africa said that investment would “be mostly driven by [the] expansion of [our] trade relationship”. And a reserve manager of another central bank in Africa said: “We are likely to continue increasing our allocation to Chinese assets due to the need to match our assets to liabilities, given the rising proportion of debt denominated in Chinese yuan.”

Of the 22 central banks of respondents (or 32.4%) that said they did not expect to have invested in the renminbi by 2035, nine were in the Americas, six in the eurozone, six in Europe and one was in the Asia-Pacific region.

Over the last year, have you changed your view on the euro as a reserve currency?

Many more reserve managers have come to view the euro as a less attractive currency over the last year, though a significant number do view it positively. Sixty-nine reserve managers at central banks answered this question. Of these, 41 (59.4%) said that the euro had become a less attractive currency and 28 (40.6%) that it had become more attractive. In contrast, of the 67 central banks that responded to this question last year, 41 (61.2%) had said they thought the euro had become more appealing.

Do you plan to change euro investments in 2025?

Nonetheless, this year, slightly more central banks globally said they were preparing to increase their investments in euros (11, or 13.9%) than decrease them (8, or 10.1%). Most of the central banks planning to decrease their investments were in Europe.

“The euro has seen an improvement in its relative attractiveness as a reserve currency, driven by higher interest rates compared to the historically low rates of recent past years,” said a reserve manager of a central bank in Africa. “Additionally, our appetite [for] the euro is driven by the need to match our assets and liabilities, given the growing volume of euro-denominated liabilities.”

However, “global uncertainty, structural challenges, trade retaliatory factors, falling inflation and lower interest rates are expected to shape the euro economic outlook in 2025”, countered a reserve manager of a central bank in the Asia-Pacific region: “These factors will hinder prospects of increasing our euro investments in 2025.”

“Compared to the rest of the developed world, the euro is not doing so badly,” a reserve manager of a central bank in Europe said. However, in the past, in their view, the currency union was much more “homogenous”, but was “fragmented and fragile” now.

Echoing earlier views regarding the effects of monetary policy divergence between the Fed and ECB, “a more accelerated pace of rate normalisation by the ECB will probably result in a weaker euro versus the dollar”, a reserve manager of a central bank in the Americas said. The expected trajectory of “euro-dollar parity” would also be a factor, the reserve manager of a central bank in the Middle East agreed.

What is the main hurdle for your institution to start investing in euro-denominated assets, or increase current allocations?

Low rates/low yield compared with the dollar emerged as the main hurdle identified by central banks for investing in the euro (49, or 73.1%). Around half of the 67 respondents to this question cited weak growth prospects.

“Given the anaemic growth, political turmoil and lack of reforms”, a reserve manager of a central bank in the Americas said, it did not see the region as attractive. Furthermore, in their view, “the eurozone faces the prospect of another debt crisis”, given the combination of high debt and deficit levels, and low long-term growth potential exacerbated by weak productivity. “Exports face the risk of US tariffs,” they added. “Trade policy uncertainty may weigh on business sentiment.”

Offering a different perspective, a reserve manager of another central bank in Europe said: “Despite subdued growth prospects and [a] deteriorated fiscal situation in the eurozone, the euro offers a developed payment system, mature financial markets, stable financial system – second only to the US market.”

“Although we trade with the eurozone, most of these trades are settled in USD,” said a reserve manager of a central bank in Africa.

Do you see the role of gold in your reserves changing in the next year? (Please tick all that apply.)

“The price is too high,” a reserve manager of a central bank in Africa said. However, despite record-high gold prices, 27 out of 72 central bank respondents to this question (37.5%) said they expected to increase their allocation to gold.

By geography, central banks in Africa were most likely to increase their gold allocation in relation to other institutions in the region (10, or 83.3%), and globally.

Twelve central banks out of 39 (30.8%) respondents said they planned to manage gold more actively.

If planning to increase allocations, why? (Please tick all that apply.)

Among the 27 central banks planning to increase their gold allocations, most saw it as a portfolio diversifier (25, or 92.6%). Many also see it as a long-term store of value (20, or 74.1%), a good performer during times of crisis (20, 74.1%) and a geopolitical diversifier (19, or 70.4%).

In contrast, “at present, we do not hold gold as part of our reserves, and that is not going to change for the foreseeable future”, a reserve manager of a central bank in the Americas said: “Besides being a highly volatile asset class, the logistics and custody are more cumbersome.”

“The volatility of the gold price poses a challenge, given our risk tolerance and risk budget,” added a reserve manager of another central bank in the Americas.

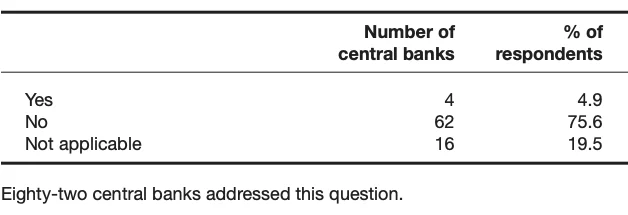

Have you changed your gold storage arrangements over the last year?

Four central banks (4.9% of respondents) said they had changed their gold storage arrangements over the past year.

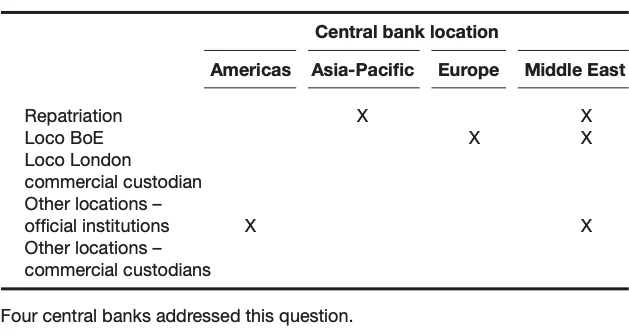

If yes, where did you move gold to? (Please tick all that apply.)

A central bank in Europe moved its gold to the BoE, a central bank in the Americas moved it to official institutions in other locations, while a central bank in the Asia-Pacific region repatriated its gold. A central bank in the Middle East executed all three operations.

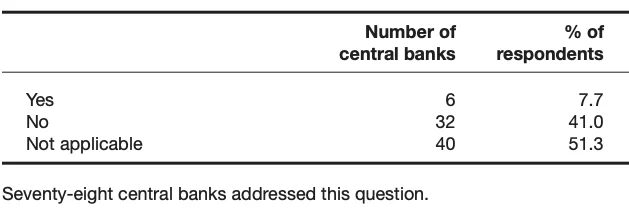

Is the current price of gold preventing you making further purchases?

The price of gold is at a historical maximum, and a small number of central banks said the current price was prohibitive to purchasing more (6, or 7.7%).

“Due to the significant price increase during 2024 and early 2025, the right moment to increase [the] allocation of gold assets is for sure a challenge because of its price volatility,” said a reserve manager of a central bank in Europe.

“Given the low amount of holdings, the extent to which we want to increase is being limited due to all-time-high prices, to mitigate any future potential mark-to-market losses,” a reserve manager of a central bank in the eurozone agreed.

“Our plan is to purchase gold locally using our local currency,” said a reserve manager of a central bank in Africa.

Which of the following best describes your attitude to exchange-traded funds (ETFs)?

One-quarter of central banks said they were investing in ETFs, with 12 (14.1%) considering investing in now, and a further 19 (22.4%) open to considering investing in the future. Thirty-two central banks (37.6%) out of 85 respondents to this question said they had no interest in investing in ETFs.

If investing in ETFs, please say which underlying asset classes they give exposure to. (Please tick all that apply.)

Most central banks that used ETFs used them to gain exposure to equities (17, or 77.3%). Of the four central banks using ETFs to gain exposure to EM debt and/or equities, two were in the eurozone, one in Africa and one in the Asia-Pacific region. “Gold ETFs provide an easy way to diversify investment portfolios, as gold often has a low or negative correlation with other asset classes like bonds,” said a reserve manager of a central bank in Africa.

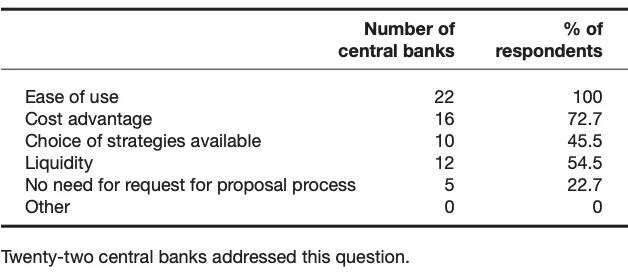

What are your reasons for using ETFs? (Please tick all that apply.)

All central banks that used ETFs and gave the reasons for their use (22, or 100%) cited ETFs’ ease of use. Many also identified a cost advantage (16, or 72.7%). Around half pointed to liquidity (12, or 54.5%) and the choice of strategies they afforded (10, or 45.5%).

“Exchange-traded funds allow for broad, diversified exposure towards equity markets without operational challenges typical of direct investment”, a reserve manager of a central bank in Europe said, including trading and settlement, accounting, corporate actions, and taxation. As the ETF market had developed, this deepened its liquidity, fees had become lower and there had been the emergence of tailored funds, they added.

In further comments, reserve managers gave details on a range of approaches to investing in ETFs, citing both internally managed portfolios and allocations via external fund managers.

“We are utilising ETFs in our internally managed portfolios as they easily facilitate diversification into spread sectors,” said a reserve manager of a central bank in the Americas. “We prefer giving mandates to external fund managers, to better tailor allocations/engagement to our impact objectives,” said a reserve manager of a central bank in the eurozone.

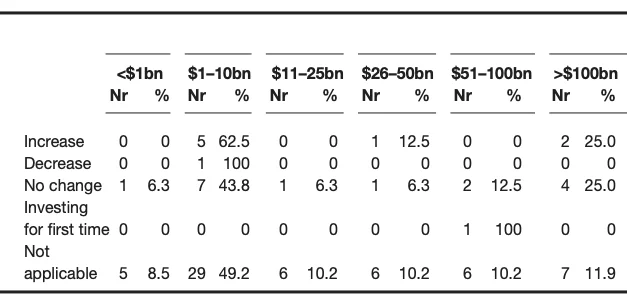

Are you considering a change in the percentage of your reserves held in equities in the next 12 months?

Eight out of 85 (9.4%) central banks said that they were considering a change in the percentage of reserves held in equities and were planning to increase their equity investments in 2025 (9.4%). “Our long-term investment strategy assumes gradual increasing of exposure towards equities, but the exact timing will depend on market conditions,” a reserve manager of a central bank in Europe said. Just one central bank was planning to decrease equity investments (1, or 1.2%), and another said it was investing for the first time.

Central banks around the world are still explicitly prohibited from investing in equities. “The extant statute doesn’t allow exposure in equities,” said a reserve manager of a central bank in the Asia-Pacific region. “Not investing in equities, and not considering due to prohibition by governing legislation,” a reserve manager of a central bank in Africa said.

By reserve holdings, most of the central banks that said they were planning to increase their equity investments held between $1 billion and $10 billion in reserves. However, two central banks managing over $100 billion were also planning to increase their equity investments over the next 12 months.

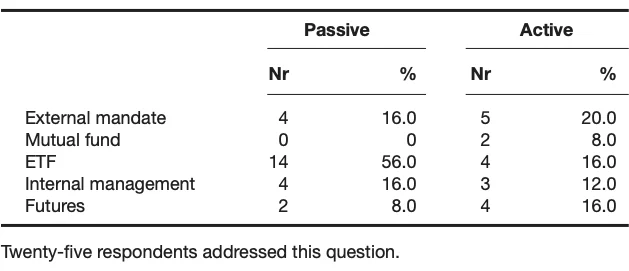

How do you invest in equities? (Please tick all that apply.)

Most central banks investing in equities said they passively used ETFs (14, or 56.0%).

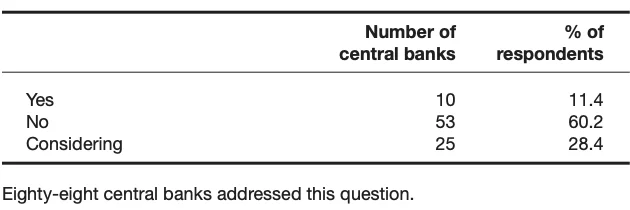

Are you using AI or machine learning (ML) to optimise your reserve management operations?

Last year, reserve managers viewed the potential of AI positively, with 82 out of 88 (93.2%) agreeing that they thought it would help to optimise their portfolios in areas such as rebalancing strategies, risk-adjusted returns and tax efficiency.

This year’s data reveals a more tentative approach to implementing the technology. A minority of central banks were actively using AI or machine learning to optimise their reserve management operations (10, or 11.4%).

While reserve managers continued to express the potential of AI in reserve management, many also expressed caution with regard to the risks.

AI could analyse “vast amounts of structured and unstructured data” such as market trends, economic indicators and geopolitical events, to provide actionable insights and improve the quality of investment decisions, a reserve manager of a central bank in Africa said. “We use ML techniques in the quantitative duration model as an input in our active portfolio management,” said a reserve manager at a central bank in the eurozone. A reserve manager of another eurozone central bank added that the central bank was “investigating how to use AI for more efficient market intelligence and synthesis of market research”.

“Several internal studies and simulations are being performed to assess the risk/benefit relations of including this new technology in allocation processes,” said a reserve manager of a central bank in the Americas. Another added: “Due to the risks involved, using AI to manage reserve operations is not considered an option now. However, staff are currently exploring/learning how to use AI to support other areas of reserve management, such as market monitoring and portfolio analysis.”

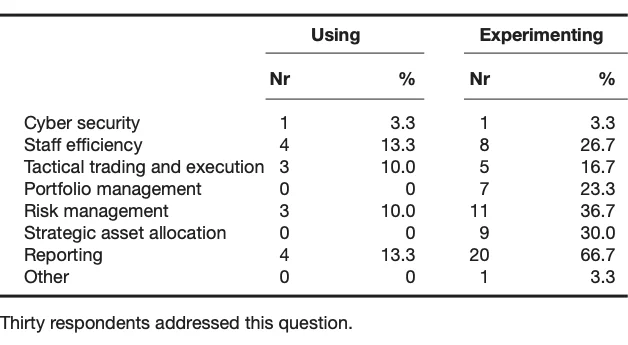

In which areas are you currently using or experimenting with AI? (Please tick all that apply.)

Of the 30 central banks that revealed if they were currently using or experimenting with the technology, staff efficiency and reporting were the most common areas to which AI was currently being applied (4, or 13.3% each). Some central banks were also using AI in tactical trading and execution, as well as risk management (3, or 10.0% each). Many (20, or 66.7%) were experimenting with using AI in reporting. Eleven (36.7%) were experimenting in applying AI to risk management, nine (30.0%) to strategic asset allocation and eight (26.7%) to staff efficiency.

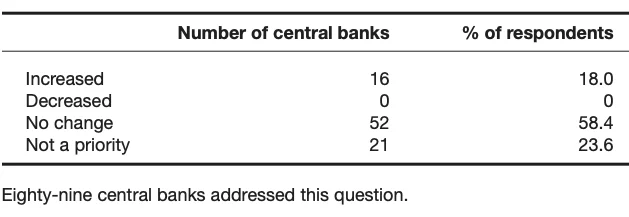

Has your prioritisation of socially responsible investing (SRI) changed over the last 12 months?

More central banks were moving to make socially responsible investing a priority. Sixteen (18.0%) said their prioritisation of SRI had increased over the last 12 months.

“The FX reserve policy was amended to explicitly communicate the intention to contribute towards the strategic goal of the [central bank] for promoting a green sustainable economy, and making positive measurable social and climate impact,” said a reserve manager of a central bank in Europe. “It is, however, stipulated that this goal is subordinate to the principles of safety, liquidity and profitability.”

“We decided to double its dedicated green bond portfolio during the year 2024, and have successfully completed this operation,” said a reserve manager from another central bank in Europe.

“We are still investigating how to be more active in this market segment,” said a reserve manager of a eurozone central bank. Similarly, “we remain interested in this topic, but we are still in the early phase, with no concrete steps taken yet”, a reserve manager of a central bank in Europe said.

“While our prioritisation of SRI in reserve management operations has not significantly changed over the past 12 months, there has been a growing awareness among management of the importance of SRI and an increasing appreciation for SRI instruments,” said a reserve manager of a central bank in Africa.

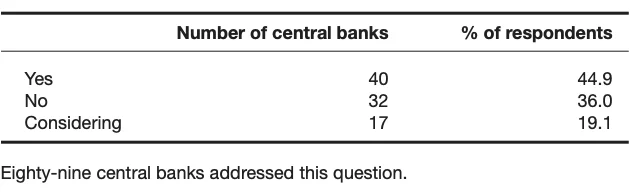

Does your central bank incorporate an element of SRI into reserve management?

The majority of central banks were either already incorporating an element of SRI in reserves (40, or 44.9%) or considering doing so (17, or 19.1%).

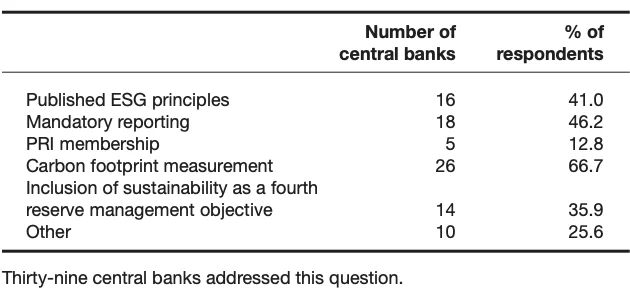

If yes, does it include? (Please tick all that apply.)

Most central banks that incorporated SRI into their reserves included carbon footprint measurement, many also used mandatory reporting (18, or 46.2%) and a published set of ESG principles (16, 41.0%). Fourteen central banks (35.9%) included sustainability as a fourth reserve management objective.

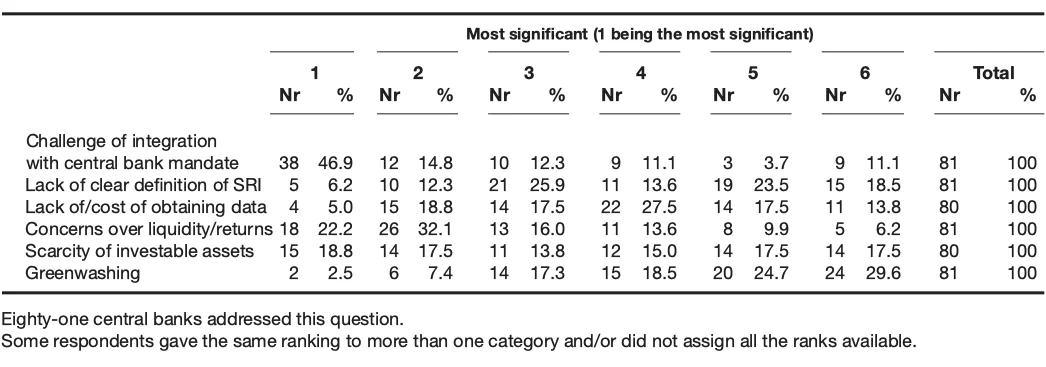

Which in your view are the most significant obstacles to incorporating SRI into reserve management? (Please rank the following 1–6, with 1 being most significant.)

Almost half of respondents (38, or 46.9%) identified the challenge of integrating SRI with their institution’s mandate as the most significant obstacle to incorporating SRI.

“Many reserve managers may be hesitant to embrace SRI due to concerns that prioritising ESG criteria could lead to underperformance,” said a reserve manager of a central bank in Africa. “There is an ongoing debate about the trade-off between sustainability and financial returns, particularly when short-term returns or liquidity are paramount in reserve management.” However, they added: “The growing interest in sustainability, coupled with advancements in ESG data, green finance initiatives and regulatory changes, may help mitigate some of these barriers in the near future”.

“There is generally a perception that prioritising SRI may come at the expense of higher returns,” said a reserve manager of a central bank in Africa. “Additionally, the absence of uniform metrics and reporting standards makes it difficult to understand and compare the different available investments.” “Anti-ESG backlash” was also a concern, a reserve manager of a eurozone central bank said, as well as the additional reporting burden.

“Sustainability goals are mainly within the government’s mandate, and such initiatives could impact [the] central bank’s independence,” said a reserve manager of a central bank in Europe. “Besides, SRI is conditional on access to adequate, reliable, coherent, transparent data – and this is still a challenge.”

Note

1. Percentages in tables may not sum to 100 because of rounding.

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@centralbanking.com or view our subscription options here: www.centralbanking.com/subscriptions

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com