Assets versus debt

In the years following the Industrial Revolution, a historical shift occurred: countries moved away from agriculture and mining to manufacturing activities and then to services. This economic transformation was critical for growing productivity, creating jobs and reducing poverty. Most developing countries have been attempting to catch up with industrial countries since World War II but have failed – some seemingly trapped as exporters of natural resources and primary products.

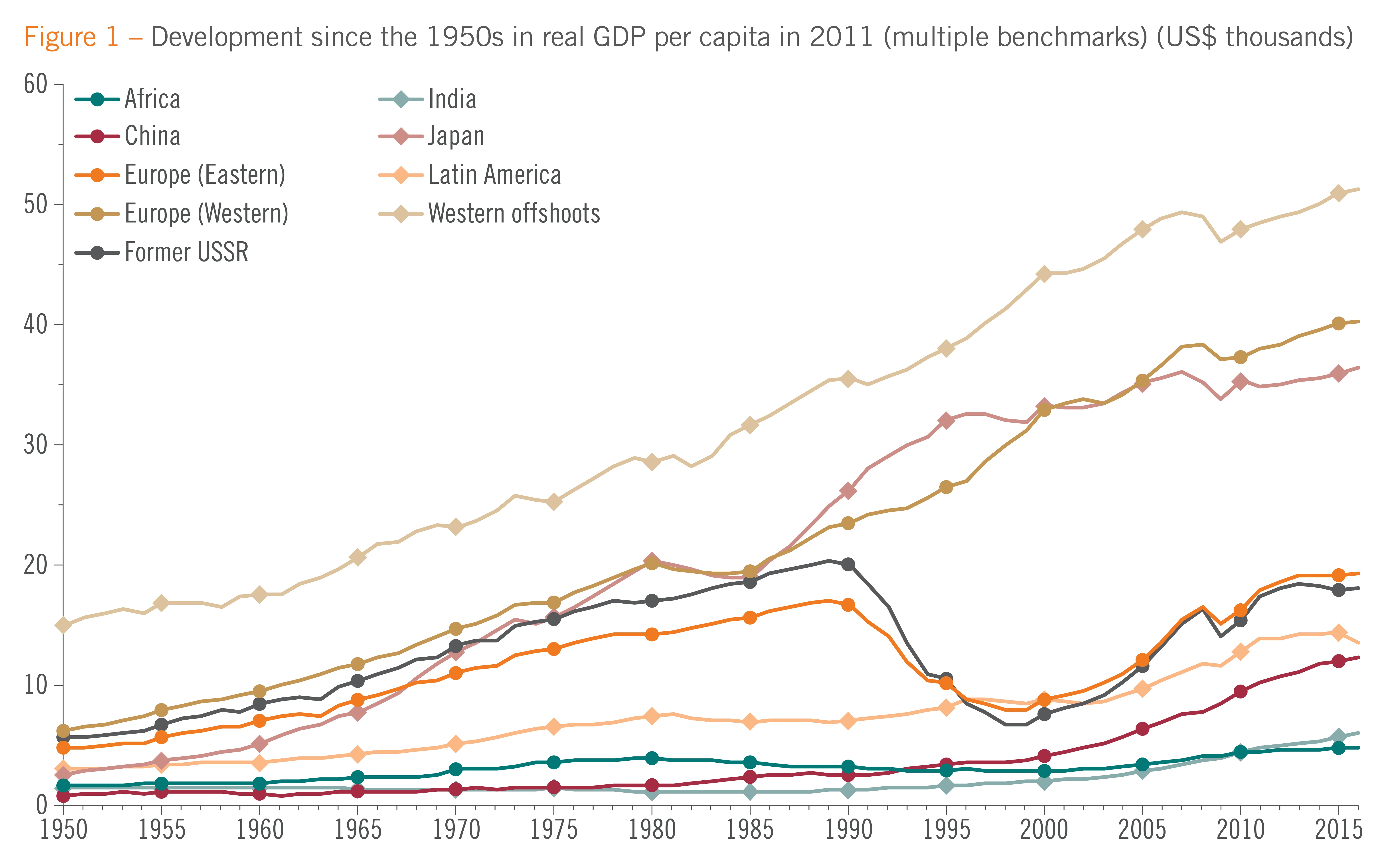

In the past half century, only 28 countries have closed the income gap with industrial countries by 10% or more. Of these, only 12 are non-European, non-resource-based countries. China, for example, had a per capita income one‑fifth that of the US in 2016, despite tremendous efforts to catch up (see figure 1).

Africa has seen its share of GDP in manufacturing decline over the past 40 years – failing to become an industrialised continent. A critical question for economists must now be: why is catching up so difficult? Why have so many African countries experienced deindustrialisation for four decades?

Is North–South aid effective?

Since the 1960s, more than $4.6 trillion in gross official development assistance (ODA) has been transferred to developing countries, including bilateral and multilateral aid. However, a substantial amount of the world remains in extreme poverty and is enduring stagnant growth. Mainstream economics has, for two decades, paid little attention to structural transformation and industrialisation, and too few resources have been invested in infrastructure bottlenecks. The power sector in Africa has been ignored by donors since the 1990s, leading to deindustrialisation in many countries. Western aid programmes did not – and will not – tell developing countries how to use industrial policies to develop manufacturing sectors. They do not help countries climb the technology ladder, because of their vested interests and because industrial policies have been taboo in many multilateral and bilateral development institutions.1

Traditional North–South aid as currently defined is not as effective as desired. However, South–South development co-operation – which combines trade, aid and investment as well as knowledge and skill dissemination – can utilise the comparative advantages of each development partner and complement traditional North–South aid.

China’s comparative advantages to help others

China combines trade, aid and investment to assist other developing countries in gaining capacity for self-development. It helps build the hard and soft infrastructure necessary for structural transformation. ‘Southern’ countries such as the Brics nations – Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa – are closer structurally and economically to many low-income developing countries. As is well known, if trade allows each partner to utilise its comparative advantages and achieve a win-win – what then are China’s major comparative advantages?

First, China has proposed enhancing global connectivity through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), in part because it has demonstrated comparative advantages in building infrastructure, including hydroelectric power stations, highways, ports, railways and telecommunications. China’s labour costs for project site foremen is one-eighth of those in member states of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Its vast domestic market and railway network allow China to realise the ‘economy of scale’ other countries cannot achieve: for example, the construction cost for high-speed rail is only two-thirds that in industrial countries.2A recent study from the World Bank highlighted that the economic rate of return from investing in high-speed rail in China is estimated to be 8%, higher than in any other country. China has successfully co-operated on infrastructure projects in Africa, including the Mombasa–Nairobi standard gauge railway in Kenya and Maputo–Katembe Bridge in Mozambique.

Second, China has a comparative advantage in 46 out of 97 – mostly manufacturing – subsectors and is using this to help other developing countries achieve mutual wins. As labour costs rise in China, its labour-intensive industries are relocating to other low-wage, developing nations, providing millions of job opportunities; Southeast Asia and East Africa have emerged as attractive alternatives. Chinese outward direct investment has created more jobs than the direct investment of others.

Third, the concept of ‘patient capital’ aids understanding of the financing of the BRI. Based on a culture of Confucianism – a system of social and ethical philosophy – China and several other east Asian economies are ranked highly in the ‘long-term orientation’ index.3

In our joint paper, The new structural economics, we propose the concept of patient capital – capital to be invested in a ‘relationship’ in which stakeholders/investors are willing to take a stake in a host country’s development (often in the form of equity-like investments). China, the Republic of Korea, Singapore and other East Asian countries have more patient capital in the form of net foreign assets (NFAs). Countries with long-term orientation possess higher savings rates and a larger amount of NFAs.

In a 2018 paper, Stephen Kaplan investigates the implication of Chinese patient capital in Latin America and notes: “Chinese state-to-state lending reduces reliance on conditionality linked Western financing, leading to higher budget deficits.” These results suggest that Chinese financing could be a developmental opportunity, but only if governments invest wisely.

South–South co-operation could be win-win

We must go beyond aid with a broader concept of development financing inclusive of South–South development co-operation. Differing from the OECD’s ODA definition, South–South development co-operation combines trade, aid and public and private investment, and utilises the comparative advantages of each country and their intimate know-how on development. It is therefore more effective in overcoming bottlenecks in partner countries.

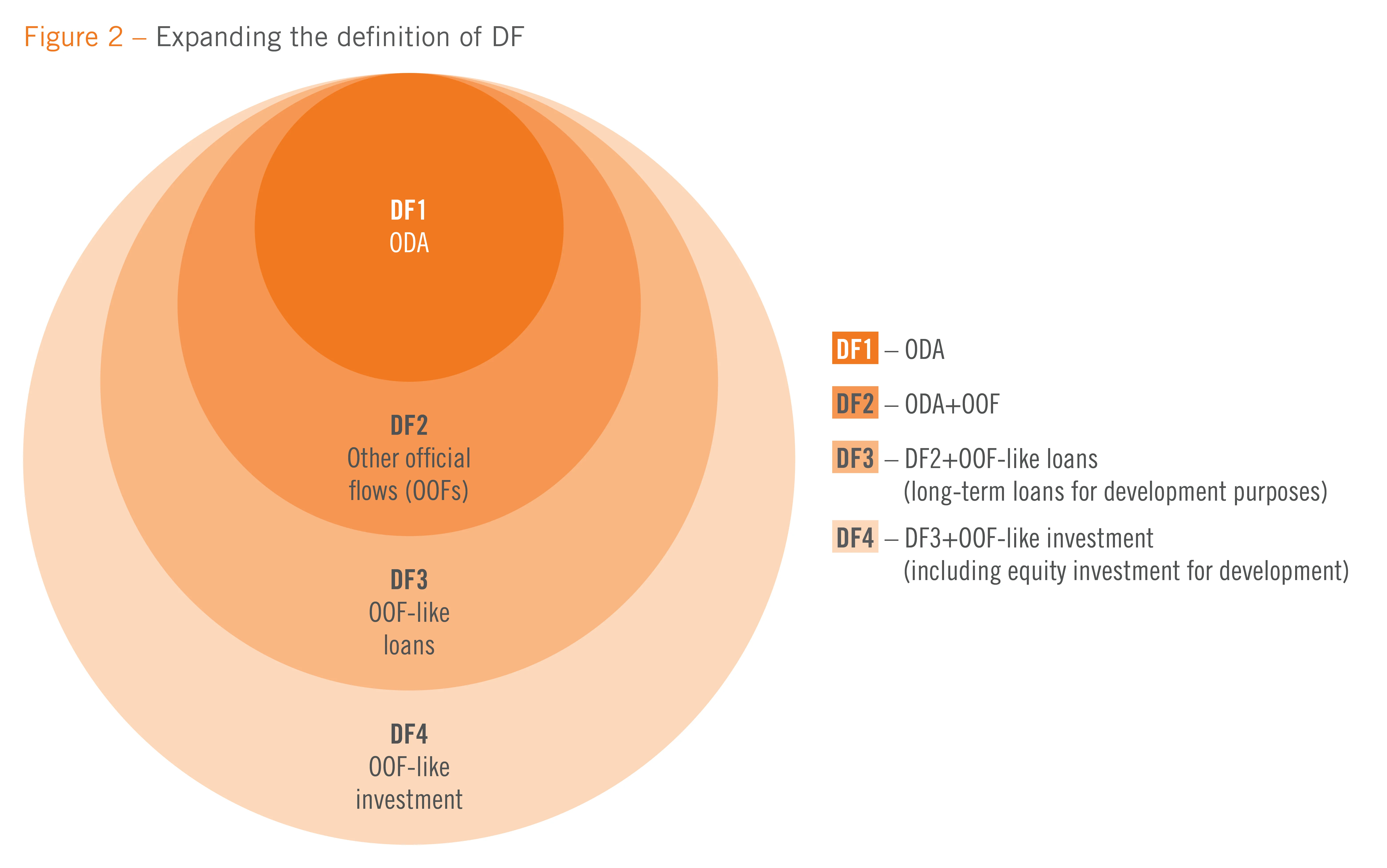

An analogue to development financing can be found in the definitions of money type (M), such as M0, M1, M2 and M3 and total social financing. Development finance (DF) is divided into DF1, DF2, DF3 and DF4, as defined in figure 2. A clearer set of definitions on DF would facilitate transparency, accountability and selectivity by development partners, encourage sovereign wealth and pension funds to invest in developing countries, and facilitate blended financing or public–private partnership.4

It should be stressed that DF3 includes long-term loans for development purposes such as bottleneck-releasing infrastructure, and DF4 includes equity investments from state investment funds such as the Silk Road Fund, the China–Africa Development Fund and many strategic investment funds, as well as the International Finance Corporation, the UK’s CDC, and the US’s Overseas Private Investment Corporation, and the newly established US International Development Finance Corporation. If one accepts these broader definitions, then the debt-to-equity swap is not unthinkable – it is merely normal practice in the capital market.

Why the debt-to-GDP ratio is misleading

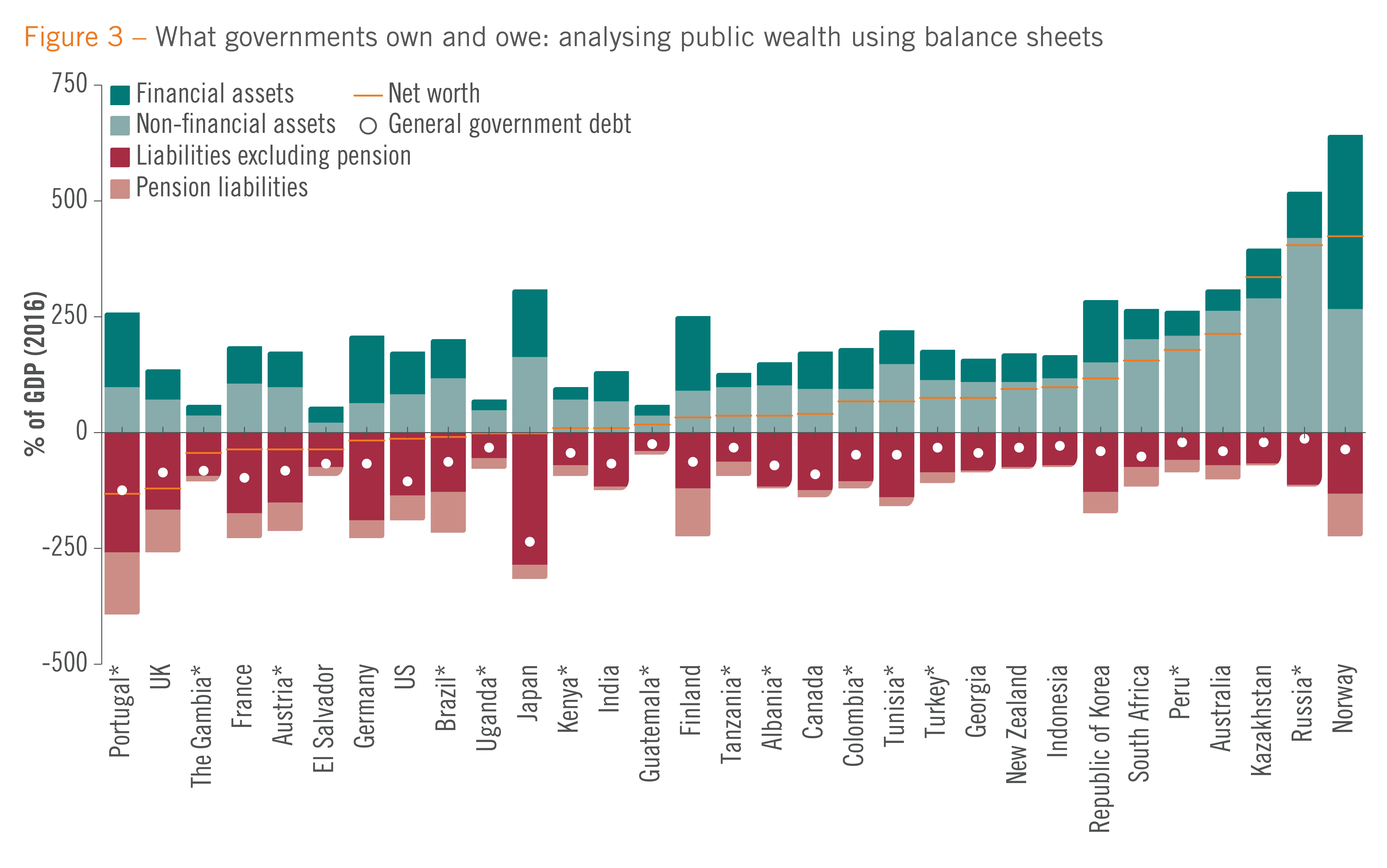

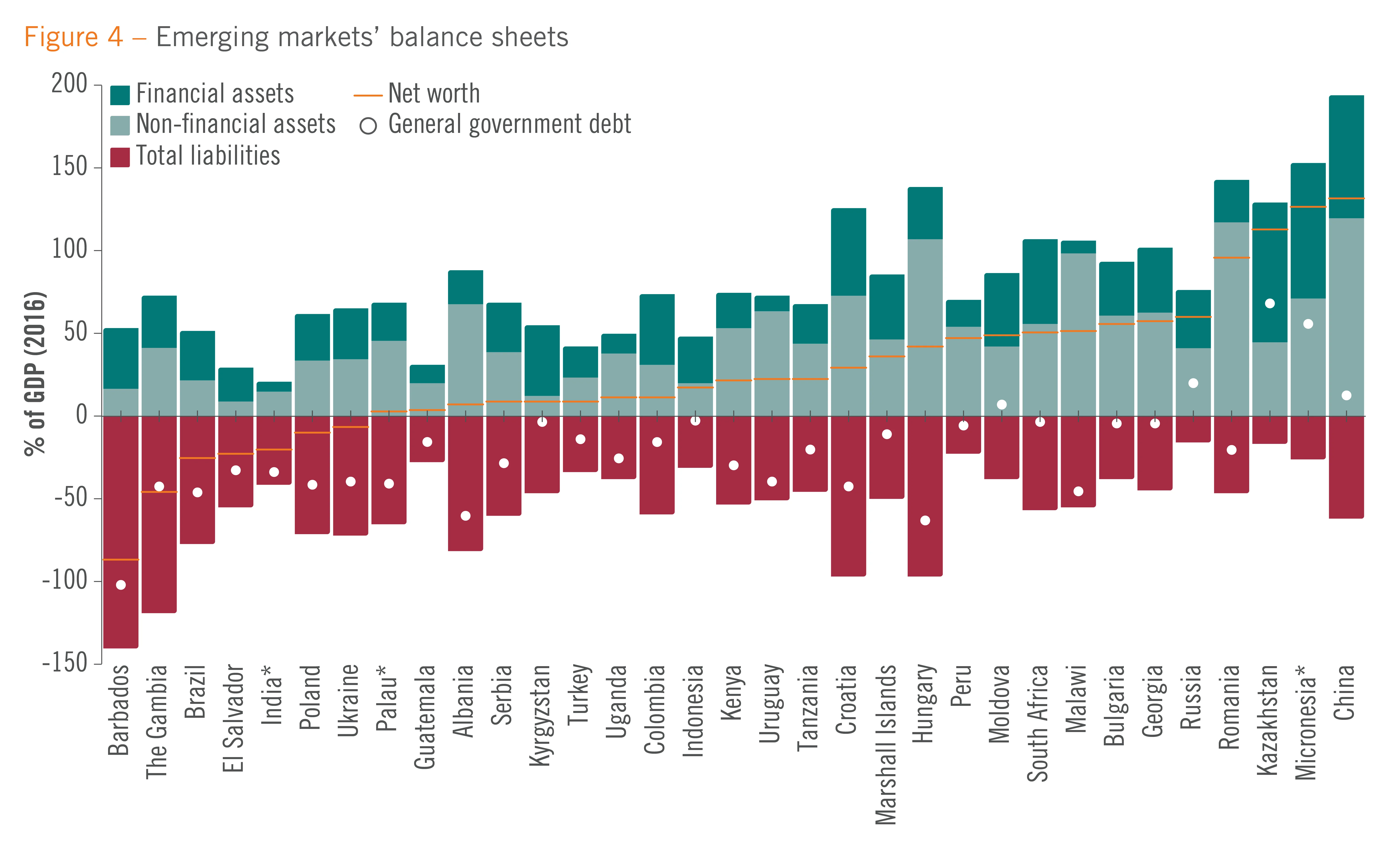

Neoliberalism may have been overly constraining in the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank’s debt sustainability framework, which requires improvement. Current research on the public sector balance sheet, and on ‘what governments own and owe’ is welcomed as it emphasises public sector net worth (see figures 3 and 4). Net worth is effectively assets minus liabilities – a far more comprehensive definition than the misleading debt-to-GDP ratio. Debt-to-GDP is narrow and misleading because:

- It does not distinguish by type of debt – for example, domestic or foreign

- It does not distinguish what the debt is used for – consumption (salaries or pensions) or investment

- It does not show whether the GDP will be affected in the long term after the completion of the project.

Source: IMF Fiscal Monitor, Autumn 201811

Source: IMF Fiscal Monitor, Autumn 201811

Some sections of the media have consequently accused China of “debt-trap diplomacy”, despite a lack of empirical evidence. For instance, a study by the Center for Global Development in 2018 estimated a “worst-case scenario of future debt”, and identified eight countries – Djibouti, Kyrgyzstan, Laos, the Maldives, Mongolia, Montenegro, Pakistan and Tajikistan – where debt to China might push debt-to-GDP ratios beyond 50%–60%. However, there is little strong empirical evidence that this level of debt will be ‘dangerous’, as many countries have experienced similar levels of debt.

According to the IMF, the public sector’s net worth is what matters. “China has substantial government assets, reflecting years of high infrastructure investment. These assets are larger than their liabilities, putting net worth well above 100% of GDP – the highest among emerging economies. This is a significant buffer compared with total debts of public corporations, particularly considering that public corporations also have assets. So, while debt-related risks in China are large, there are also buffers” (see figure 4).

While the valuation of government non-financial assets is uncertain, the net financial worth, which excludes these non-financial assets, is much smaller. Excluding non-financial assets, “China’s general government’s net financial worth remains positive, at 8% of GDP in 2017 – although it has deteriorated in recent years.” However, “subnational governments own land resource and invest in infrastructure, which could provide buffers and generate revenue to service their debt […] Second, the government’s holding of state-owned enterprise equity could be higher than the conservative estimates presented here.”11

The IMF study illustrates how public sector assets could act as a buffer to allow governments with high public wealth to withstand recessions better than those with low public wealth. Stronger balance sheets allow governments to boost spending in a downturn.

China has been trying to co-finance and co-build infrastructure projects, such as hydropower stations, power grids, highways, railways, ports, bridges and internet technology – public sector assets that can be managed to generate revenue and create jobs. If planned carefully, they can help generate economic growth, develop the manufacturing sector, promote exports, create jobs and reduce poverty. Therefore, looking at the debt-to-GDP ratio without examining the asset side is misleading and hypocritical.

All governments can better manage resources by saving more and building public sector assets such as bottleneck-releasing infrastructure and then identifying their existing comparative advantages. Targeted policies to develop these sectors that are consistent with the country’s latent comparative advantages should then be implemented. If you need a success story, look no further.

Notes

1. Justin Yifu Lin and Wang Yan (December 2016), Going beyond aid: Development co‑operation for structural transformation, Cambridge University Press, p. 158

2. Idem, Chapter 5

3. G Hofstede, G Jan Hofstede, M Minkov (July 2010), Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind, Third Edition: Software of the Mind: Intercultural Cooperation and Its Importance for Survival, McGraw-Hill, London

4. Justin Yifu Lin and Wang Yan (December 2016), Going beyond aid: Development co‑operation for structural transformation, Cambridge University Press, p. 175

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@centralbanking.com or view our subscription options here: www.centralbanking.com/subscriptions

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com