China and the Middle East – A priceless pivot

China’s engagement with the Middle East in real economy terms is strong – and likely to get stronger. This is a solid foundation to enhancing financial co‑operation going forward. The timing also appears to be right, in that the West is suffering from ‘Middle East fatigue’, and the US administration’s talk of retrenchment from the region is making many nearby countries much more receptive to Chinese outreach.

Equally important, China no longer perceives the Middle East and North Africa (Mena) as a “chaotic and dangerous graveyard, burying empires”, as Li Shaoxian of Ningxia University put it. It is exactly the opposite – China now recognises the region as the key to unlocking its status as a world power. Why do China and the Middle East need financial co‑operation? There are at least five simple reasons:

1. China is the largest trade partner in the region. It is the largest trade partner of 11 Mena countries: Iran and 10 Arab League nations. Across a broader geographical area, China’s trade with the 22 Arab League nations reached US$244.3 billion in 2018; trade with Iran, Turkey and Israel totalled $72 billion. Combined, Mena accounts for more than $300 billion of trade with China.

2. China is already a leading source of foreign direct investment (FDI) and, increasingly, an important source of project financing in the region. China became the largest source of FDI in the Middle East in 2016. In 2017 alone, the country signed investment contracts worth $33 billion with Arab countries.

Future projects linking China’s domestic development programme to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) are likely to enhance trade, investments and financial linkages. As of mid-2019, China had signed agreements with 21 Mena countries, including 18 Arab League nations, on a joint BRI project.

3. The Mena region already hosts more than 1 million Chinese expatriates. This number is likely to increase as China ups its engagement in post-war reconstruction in Iraq, Syria, Yemen and, possibly, Libya.

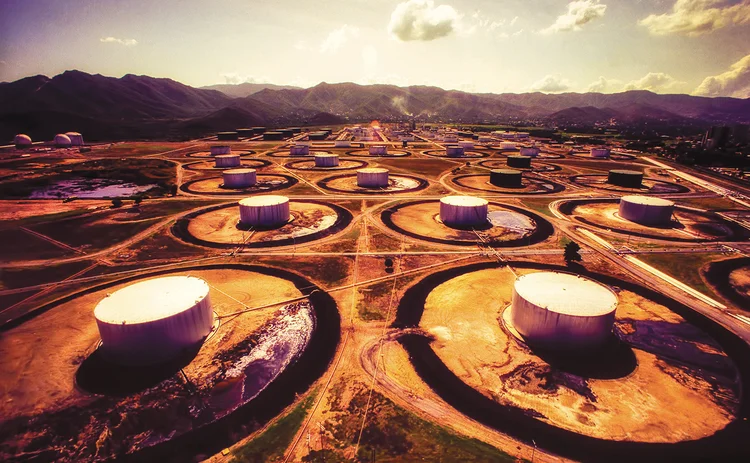

4. China is the biggest global importer of crude oil. It imported roughly 500 million tonnes in 2019, half of which came from the Middle East. Oil- and gas-rich Gulf states thus account for upwards of 80% of China’s trade with Arab nations.

5. Demand from some Middle Eastern countries for deeper financial and economic co‑operation with China is likely to grow on the back of the increasing threat of economic sanctions, and weaponisation of the US dollar and payment systems by Washington. Countries such as Iran, Turkey and Russia have publicly expressed a strong desire to use local currencies for trade and investment transactions in the future.

In short, China’s growing economic presence in the Middle East necessitates stronger financial co‑operation.

Swap lines and de-dollarisation

Discussions now need to be opened on what sort of financial co‑operation is likely. There are substantial differences in political, social and economic conditions across the Middle East. It would therefore be difficult to implement a single framework for financial co‑operation catering to the needs of all countries. Oil‑rich surplus countries and deficit countries have different needs. There are therefore multiple channels of financial co‑operation.

China’s rise has already led to the renminbi officially becoming a global reserve currency. It currently represents around 10.9% of the International Monetary Fund’s special drawing rights currency basket. This makes the renminbi the third-largest reserve currency after the US dollar and the euro. Central banks in Middle Eastern countries are likely to hold, in the future, part of their reserves in renminbi-denominated assets.

One area of co‑operation, as a result, could be bilateral currency swaps to achieve a higher degree of financial stability in the region. China already has 36 bilateral currency swap lines globally, and standing facilities that are rarely used; Middle Eastern trade partners could benefit from them.

Second, the weaponisation of the dollar – the currency being used as a weapon in imposing economic sanctions – is likely to lead to de‑dollarisation in the long term. If deglobalisation is going to be a global long-term trend, it will be partnered by de‑dollarisation.

The development of the internet and blockchain-based payment systems will probably influence multiple global systems. China and Middle Eastern countries could facilitate trade in renminbi or local currencies. Some countries are already seeking ways of reducing their vulnerability to the continuing threat of US sanctions and are considering ways of using local currencies for trade and investments.

The Brics nations – Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa – are reportedly developing a new universal payment system to challenge the Swift international payment network. More recently, Kirill Dmitriev, chief executive officer of the Russian Direct Investment Fund, unveiled some striking numbers: foreign trade payments in dollars have dropped from 92% to 50% over the past few years, while international ruble transactions have risen from 3% to 14%. The Brics nations are also said to be considering a new common cryptocurrency for mutual payments as another way of working around the dollar.

However, the use of renminbi seems a more feasible alternative for oil and gas exporters in the future, as it is hard to sustain trade in local currencies with persistent deficit countries.

Third, the close economic integration between China and Middle Eastern countries also requires market-based financing for corporates and governments. China’s Panda bond market is another avenue for co‑operation. Panda bonds are renminbi-

denominated notes sold by non-Chinese issuers in mainland China. This onshore product, which offers international borrowers a way to tap domestic Chinese investors, is likely to continue to develop and internationalise going forward. The investor base is also likely to become international. This will be a great route forward for deficit countries.

Finally, co‑operation between sovereign wealth funds in China and Middle Eastern countries is also an option. The success of any co‑operation – in particular financial – between China and the Middle East will be largely dependent on a strong policy dialogue.

Renminbi at the top table

As previously alluded to, the world is likely to move towards a multicurrency global monetary system. The renminbi looks set to play a much stronger and more significant role in international trade and finance. This also requires China to continue reforming its financial markets, further opening up, and deepening capital markets – something the Chinese government today, and in the past, has made very strong commitments to.

Deeper financial co‑operation also requires, first and foremost, mutual trust, the existence of which is evident between the two regions. No country in the Middle East sees China’s rise as a threat, and there is already a strong strategic and political dialogue between China and almost all countries in the region. This is a good backdrop to build a win-win relationship across the border between China and the Middle East.

Arguably, the regions need each other. China’s growth has been stuttering in the face of declining returns to investments, a falling working-age population and thus declining productivity growth. China’s search for new growth drivers is going to become even more pressing. Africa – as well as the Middle East – has an extremely young population that can serve this need. Many countries, except members of the Cooperation Council for the Arab States of the Gulf, are in the growth phase.

Middle Eastern countries also need China because they are in dire need of diversification. The International Energy Agency (IEA), in its latest World energy outlook report, foresees global demand for oil reaching a plateau around 2030. Youth unemployment rates in the Mena region have been the highest in the world for more than 25 years; in 2017, they were around 30%.

The regions are a perfect match: China is searching for growth drivers globally and the Middle East presents good opportunities. Meanwhile, the Middle East needs Chinese investments and financing to accelerate its own development and industrialisation.

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@centralbanking.com or view our subscription options here: www.centralbanking.com/subscriptions

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com