Central bank of the year: Bank of Canada

Canadian central bank has stood out for ever-improving levels of transparency and forward-looking management

The Bank of Canada represents something of a benchmark for a modern-day, operationally independent central bank. It pursues its core areas of responsibility with exemplary openness and ability to challenge itself. There is a demonstrable effort to generate improvements and an energy to get the job done that is matched by few of its peers.

Whether it is for currency management, trials of distributed ledger technology (DLT) in clearing and settlement, efforts to reduce reliance on external credit ratings, the revamp of its headquarters and museum, or its constantly evolving communications and website, the Bank of Canada ranks as one of the world’s most closely watched central banks.

It a challenge to pinpoint any particular year that the Bank of Canada has really stood out. There is a consistency to its performance, whatever the outside events that it faces.

But a critical factor in recognising its work during the past year was that the central bank undertook to determine whether or not its inflation-targeting mandate was still fit for purpose. This turned out to be a no-holds-barred inspection that should serve as a source of inspiration for other central banks.

Policy review

The mandate sets a 2% medium-term inflation target with a tolerance band of 1–3%. Since the implementation of its target (its current governor, Stephen Poloz, was part of the original policy framework team that devised the target in the 1980s), inflation has averaged about 2%.

But in the past few years – as has been the case in many advanced economies – recorded inflation has generally fallen short of the target. Coupled with the formation of asset bubbles – particularly in real-estate assets (in part, encouraged by low interest rates) – it has raised questions about the ongoing relevance of 2% inflation-targeting regimes.

An open debate

Rather than trying to deflect or avoid the issue, the Bank of Canada reviews its mandate by encouraging critiques by both internal and external parties, and publicly shares many of its findings. This has enabled staff at the central bank to “get out of the day-to-day frame of mind” and “think about fundamental issues”, such as whether its current inflation target is optimal to “support the economic and financial wellbeing of Canadians”, said senior deputy governor Carolyn Wilkins in September 2017.

After much soul-searching, its most recent review ended in December 2016, with the Bank of Canada ultimately sticking with its 2% inflation-targeting mandate. But the central bank has already held a workshop with international experts in September 2017 to determine the areas of research required to test the appropriateness of its mandate for its 2021 review. It is also looking at how monetary policy should fit in with macro-prudential and fiscal policies, as well as the appropriate form and degree of transparency and communication.

Some of the areas the Bank of Canada is studying include: whether or not strict inflation targeting contributes to financial imbalances; the challenge of a low neutral interest rate, and the likelihood, viability and consequences of using unconventional policies such as negative rates (it has some concerns about the use of a central bank issued digital currency to help implement negative nominal interest rate policies) and asset purchases at the zero lower bound; as well as researching if supply shocks make it unwise to chase a 2% target at all costs.

Price level and GDP targets

The Bank of Canada is also actively reviewing the use of policies that could reduce the likelihood of hitting the zero lower bound, including raising the target or using a price-level target, which may be “too difficult” to communicate, even if central banks can “leverage the credibility” they have built up over the past 25 years to make any transition “smoother”, Wilkins said at the close of the workshop on September 14, 2017.

The central bank has also investigated the pros and cons of having a real-economy mandate, such as employment as well as a nominal GDP target. This could prove useful when there is a breakdown in the relationship between low and stable inflation and low and stable unemployment, such as when there are disruptions caused by changes in technology or an influx of cheap imports. A particular concern with a nominal GDP target is that such a regime could place strains on the independence of the central bank, as there are obvious political implications attached to such policymaking.

The correct policy mix

The Bank of Canada also recognises the need for a better understanding of the linkages between the real and financial sectors, and that work needs to be done to establish the optimal mix of monetary, macro-prudential and fiscal policies (eg, countercyclical policies, automatic stabilisers and structural policies) to get economies back to their economic potential.

“Different mixes of policy may be able to achieve the same macro outcomes in the short to medium term, but the outcomes could differ in some important respects over a longer horizon: whether indebtedness builds up in the private or public sectors, or whether the distribution of income and wealth widens or narrows,” said Wilkins at the September 2017 workshop.

The Bank of Canada is also well aware that policy co-ordination raises issues for policymakers with independent mandates. But there could be co-ordination of framework design, she added: “Complementary frameworks could deliver better outcomes, while maintaining the central bank’s instrument independence.”

Best practice

The practice of a central bank reviewing its mandate is a development that John Williams, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, believes should be happening at many more institutions, including the US Federal Reserve Board. “The Bank of Canada has a framework approach in place where it conducts a very serious, in-depth, careful analysis around its policy framework every five years,” Williams told Central Banking in an interview in September 2017. “We and other central banks should follow that example.”

Reaction function

The Bank of Canada has also studied the trade-off between the benefit of additional clarity by revealing the potential future path of interest rates versus the cost of the information lost from the market when actions are telegraphed in advance. As a result, it abandoned its forward guidance on the path of interest rates in 2013, and shifted to what Poloz refers to as a “risk-management approach” to monetary policymaking.

The Bank of Canada has also studied the trade-off between the benefit of additional clarity by revealing the potential future path of interest rates versus the cost of the information lost from the market when actions are telegraphed in advance. As a result, it abandoned its forward guidance on the path of interest rates in 2013, and shifted to what Poloz refers to as a “risk-management approach” to monetary policymaking

The approach means the governing council can take into consideration financial stability concerns when setting the headline interest rate, as well any slant there may be to risks around the inflation outlook. Senior deputy governor Wilkins says this can manifest itself in a bias in policy setting, either towards aggression or caution. In a speech in November 2017, she said a cause for aggression could be when interest rates risk hitting the zero lower bound. By contrast, the recent period of unexpectedly low inflation encouraged the central bank to be more cautious about raising rates, she added.

Governor Poloz accepts that monetary policy is “an imprecise business”, and is as much an “art” as it is a “science”. He believes the 2-percentage-point inflation-control range “is a reasonable approximation of the degree of precision” that can be achieved.

He is also aware of the importance of inflation expectations and the concept of a ‘credibility dividend’ (where a credible central bank will see expectations firmly anchored at its target). He believes a logical result of the credibility dividend could result in underlying inflation becoming more stable, meaning the relationship between economic shocks and inflation become less obvious.

But Poloz said in a speech in November 2017: “We believe that there is still a link between labour market slack and wages, just as there is still a link between inflation and the balance of total supply and demand. What this means is that the closer we get to full output and employment, the greater the risk that inflation pressures will appear.”

Model revamp

As a result, the Bank of Canada is upgrading its forecasting models used to predict where inflation will be in two years’ time to help monetary policymakers calibrate their policies accordingly. It has upgraded its workhorse models, such as its terms of trade economic model, which is viewed as particularly important, given US president Donald Trump’s intentions to change the North American Free Trade Agreement. It also factors in household indebtedness into its models, which recognises that higher levels of debt make the Canadian economy more sensitive to higher interest rates than in the past.

“This issue has obvious implications for monetary policy, so we have done a lot of work this year to enhance our models to capture it,” said Poloz in December 2017.

Monetary policy

The Canadian central bank raised its key policy rate (which takes 1.5 to two years to fully feed through to inflation) three times in the past year, ending a seven-year spell of no rate rises in July 2017, when its governing council increased the overnight rate by 25 basis points to 0.75%. This rise was made in response to “robust” economic growth and the absorption of slack in the economy, with inflation expected to reach its 2% target within the next year. It also signalled that the economy’s adjustment to lower oil prices was “largely complete” and household spending remained robust, the central bank said.

Governor Poloz said there had been a “lively debate” in Canada and other countries about the appropriate setting for policy when the economy is strong but inflation low. He said the governing council had discussed the issue, and decided “a significant portion” of recent inflation weakness would likely be temporary. The uncertainty “serves to underscore” the data-dependent nature of monetary policy, the governor added.

Surprise rate rise

The Bank of Canada again raised rates by 25bp – much more controversially, this time – in September 2017. The move appeared to catch some bankers off-guard, triggering volatility in financial markets. Douglas Porter, chief economist at the Bank of Montreal, said there was “an epic fail” to communicate the likelihood of a rate rise over the summer, pointing to the fact that only six of 33 forecasters anticipated the bank’s rate rise.

But the Bank of Canada’s communications chief, Jeremy Harrison, responded that “market data indicated roughly 50/50 odds of an increase prior to the announcement”: “Evidently, a much higher percentage of trading desks were correctly interpreting the bank’s prior messaging that monetary policy would be forward-looking and data-dependent.”

Notably, second-quarter GDP (released on August 31, 2017) was higher than expected, but the data could not be discussed in public, as it fell during the monetary policy “blackout” period, when monetary officials are forbidden from speaking about current monetary policy matters. However, the episode appears to underscore that the Bank of Canada believes markets should think for themselves.

Then, on January 17, 2018, as the central bank said the Canadian economy was operating close to its potential and inflation growth approached its 2% target, the governing council increased rates by another 25bp to 1.25%. Wilkins stressed the rise was due to labour market slack narrowing “somewhat more quickly” than expected and inflation having grown more strongly than the central bank previously projected, rising just above 2% in the final months of 2017.

Financial stability

The rise in interest rates may also contribute to the effort to limit Canada’s burgeoning mortgage exposures. In its June 2017 Financial system review, the central bank says imbalances in the Canadian housing market and elevated household indebtedness were the “most important vulnerabilities”: “Highly indebted households have less flexibility to deal with sudden changes in their income. As the number of these households grows, it is more likely that adverse economic shocks to households would significantly affect the economy and the financial system.”

While high house prices have been on the central bank’s risk list for a number of years, they only reached the top of the list last year, as prices soared, particularly in the Toronto and Vancouver areas – despite regional government increasing taxes on foreign buyers and a tightening of mortgage-qualification guidelines.

With more than 80% of household debt composed of mortgages and home equity lines of credit, the central bank supported several rounds of macro-prudential measures introduced by the Canadian government and its Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions aimed at tightening mortgage finance rules, including requiring each new mortgage borrower to have the ability to manage a higher interest rate at renewal time

With more than 80% of household debt composed of mortgages and home equity lines of credit, the central bank supported several rounds of macro-prudential measures introduced by the Canadian government and its Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions aimed at tightening mortgage finance rules, including requiring each new mortgage borrower to have the ability to manage a higher interest rate at renewal time. These measures are expected to “help build up the resilience” of the financial system “over time”, said Poloz in December 2017.

A top-tier website

A key tool that has enabled the Bank of Canada to stay on message and communicate with the public in an open manner is its top-tier website. Its bilingual outreach efforts were stepped up in 2017 through the effective use of new infographics, switching from a PDF to fully digital publication and exploiting new technologies, in particular to display its banknote webpage. The common theme throughout the website is its attention to detail, which elevates its offering above virtually every other central bank’s.

Revamped headquarters

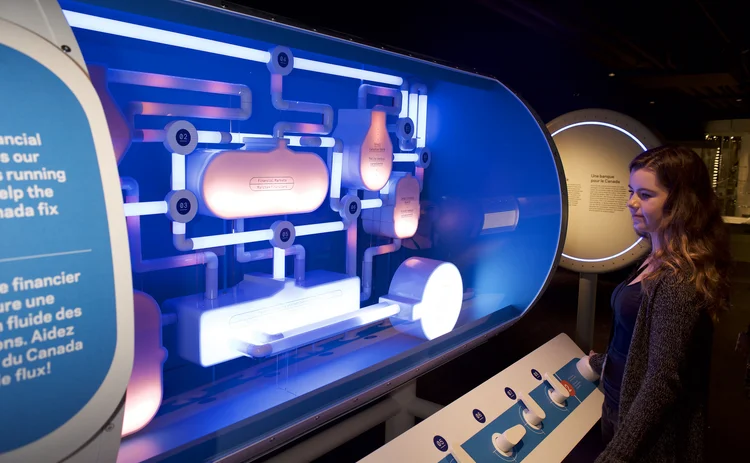

It’s not just the Bank of Canada’s virtual presence that has changed. The bank moved 1,600 of its staff back into their refurbished Ottawa head office in 2017. At the same time, the central bank relaunched its museum to commemorate Canada’s 150th anniversary on July 1, 2017. This three-year project was completed on time and on budget for a cost of C$460 million (US$369.1 million), said Poloz. As well as displaying 1,400 artefacts from the National Currency Collection (chosen from a stock of 128,000), the museum also has an educational science centre designed to educate members of the public about central banking. The museum takes an innovative approach to its interactive exhibits. Visitors begin by creating a digital avatar to represent them as they take part in activities to learn about the work of the Bank of Canada and how their own actions affect the economy. There is also a video game in which visitors must fly a rocket ship “through a galaxy of inflationary and deflationary forces” and visitors can also design their own banknotes.

Currency management

In 2017, the Bank of Canada also concluded its #banknote initiative, where the central bank let the public choose who should appear on the first denomination of its new series – a process it plans to continue for the rest of its denominations, demonstrating another aspect of its efforts to engage and build trust with the general public.

The Bank of Canada is now viewed as a pioneer in currency management. It works closely with the banknote community to create and developed new security products

Indeed, since it overcame counterfeiting problems in the early 2000s, which resulted in the quick turnaround of a new series and the subsequent adoption of polymer substrates, the Bank of Canada is now viewed as a pioneer in currency management. It works closely with the banknote community to create and developed new security products, and focused significant attention in 2017 on using its banknote data to help forecast the demand and lifecycle of notes in circulation. As a result of its new data analytics, the Bank of Canada decided to review the launch cycle of the notes, with the banknotes now being released over a longer period of time.

No more external ratings

Other important developments in 2017 included the Bank of Canada fulfilling a Financial Stability Board recommendation to wean itself off external credit ratings, allowing the central bank to make its own judgements about the risks of its main counterparties. A team of eight is now tasked with assessing the credit risk of around 80 counterparties, and their work now forms a critical input for the management of Canada’s reserves, which stood at US$84.6 billion on July 23. The central bank’s investment team does still use external credit ratings, but these are only used for validation purposes.

Project Jasper

Back in the virtual world, the Bank of Canada launched the third phase of its distributed ledger technology (DLT) project, looking to create a proof of concept for the clearing and settlement of securities using a central bank ‘cash-on-ledger’ model.

The aim of the DLT experiment is to discover if greater speed and efficiency can be achieved by automating the securities settlement process, according to Payments Canada, one of the project’s collaborators. The cash-on-ledger approach, which was also employed in phases one and two of the Bank of Canada’s ‘Project Jasper’, sees participants exchange Canadian dollars for digital tokens, which can then be transferred across the distributed ledger.

Much of the impetus in the DLT experiment has come from senior deputy governor Wilkins, who wants to explore potential ways to modernise the securities settlement process to promote the efficiency and stability of the financial system

Much of the impetus in this area has come from senior deputy governor Wilkins, who wants to explore potential ways to modernise the securities settlement process to promote the efficiency and stability of the financial system. She believes a “better settlement process” would not only support the resilience of the financial system in times of stress through “faster settlement times and reduced settlement risk”, but also lower the cost of securities transactions.

The central bank began Project Jasper in 2016, working not just with Payments Canada, but with a number of private-sector participants. In the first two phases, the project focused on exploring clearing and settlement of high-value payments across a DLT framework. But the Bank of Canada ultimately concluded a “pure standalone DLT wholesale system” was “unlikely” to match up with existing infrastructure. Nonetheless, the central bank maintained that a DLT-based wholesale payment system could still bring benefits in the way it interacts with other financial market infrastructure.

In the latest stage of the project, TMX Group – which operates the Toronto stock exchange, among other exchanges – has joined the effort. TMX vice-president John Lee said in October 2017 it was “vital” to explore innovative technologies with the potential to “optimise the business transaction process for all Canadian investors”. The central bank expects the results of the third phase to be presented at a conference in May 2018 – which will be watched closely by its peers.

Pushing the boundaries

Whether it is the keenly awaited results of its latest blockchain experiment or the policy debates informed by its monetary policy review, the Bank of Canada is helping to challenge and push the boundaries of modern-day central banking.

The Central Banking Awards were written by Christopher Jeffery, Daniel Hinge, Dan Hardie, Rachael King, Victor Mendez-Barreira, Iris Yeung, Joel Clark and Tristan Carlyle

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@centralbanking.com or view our subscription options here: www.centralbanking.com/subscriptions

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com