Arnab Das, global macro strategist at Invesco, explores the possibility of an international monetary system going back to the future, with the US less economically and geopolitically dominant

In short

- The West’s freezing of half of Russia’s foreign exchange reserves in retaliation for the invasion of Ukraine has triggered doubts about the dollar’s durability as the dominant global reserve currency.

- There are signs of some shifts in the means of payment from the dollar to renminbi, rupee and ruble in Russia’s oil trade. Yet alternatives to the dollar as a global unit of account and store of value face high barriers.

- Desire for diversification and protection point to potentially parallel payments systems instead of dollar displacement in today’s system.

Financial Cold War: freezing Russia’s liquid reserves

Freezing around $350 billion – roughly half the Central Bank of the Russian Federation’s (CBR’s) foreign exchange reserves – may be the most severe western sanctions against Russia since its invasion of Ukraine. Is the freeze, perhaps the most extreme financial weaponisation on record, proportionate to the war (itself perhaps the gravest threat to the multilateral, rules-based world order that has underpinned globalisation since the Cold War)?

Globalisation was already challenged by pre-war restrictions on cross-border flows of goods, services, capital, data and people, aimed at more conventional political and/or economic goals. Such measures reflect protectionist backlashes against poor policies, productivity, economic performance or inequality in key sectors or constituencies. Sometimes unilateral, aggressive and ineffectual, as in the Trump era, or misguided, divisive and self-harming, as with Brexit – such barriers reduce market access, scale, competition and arguably aggravate productivity problems.

Yet the sanctions, including the reserves freeze, belong in a different category and have been cast in ideological and existential terms as specific retaliation against what is perceived to be direct violation of the rules of the game – well beyond transgressions against free and fair trade or future threats to national security. They are multilateral – every Group of 7 member and many other western countries have participated. And they have continued to ratchet up as the conflict evolves.

The dollar and three functions of a global currency

Even so, the sanctity of reserves may have been violated in ways that can never be rolled back. Can any sovereign state now be sure that official reserves, private assets or other state assets are beyond the reach of other governments?

Many westerners and governments feel the international system, law, property rights and territorial integrity are under direct attack, which, they feel, cannot be allowed to stand and the aggressor should be made to pay. Freezing reserves is extreme enough – what if reserves are seized for Ukraine’s reconstruction?

If other reserve-holding countries fall foul of the policy preferences of reserve-issuing countries, could their reserves also be frozen or even forfeited? Codifying parameters and conditions for reserve freezes or seizure might restore confidence in new rules. But what if the US and its allies prefer ambiguity and uncertainty as a source of deterrence?

There may even be a general division between the West and the rest of the world. US President Joe Biden argues that the war sets up a contest between democracy and autocracy – and many non-western democracies joined UN condemnation of Russia’s invasion. However, very few have joined western sanctions. Norway, Switzerland and Japan aside, most major reserve holders are emerging market (EM) central banks, the governments of which are neutral in the conflict. Many EMs continue to trade actively with Russia.

It is little wonder that freezing the CBR’s reserves feels to many like another nail in the coffin of globalisation: Russia-Ukraine as a proxy war. These sanctions, aimed at financial/economic decoupling and uneven global participation, may be axes of a new Cold War with competing political/economic/financial systems and a non-aligned movement. These worries raise the question of whether the dollar reserve system is entering its final innings, along with Pax Americana itself, given the outbreak of war.

However, the war is not going Russia’s way. The hostilities may even be reinforcing the view that US diplomatic/military/intelligence commitments and capabilities are indispensable to western or even global stability and security. Equally, there is little evidence of declining US financial hegemony. Even though the US is no longer so much larger than other major economies such as China or the eurozone, if anything, the role of the US Federal Reserve in driving global monetary/financial conditions remains paramount and the dollar has gone from strength to strength.

Even so, efforts are under way to diversify from the dollar. One way to assess how the dollar is holding up is to track the three key, classic domestic functions of money globally – unit of account via pricing; means of payment via trade credit/settlement; and store of value via official FX reserves. The evidence points to partial diversification on some dimensions of money, implying parallel systems rather than displacement of the dollar within the existing system as happened in the sterling-dollar transition.

1. Global unit of account

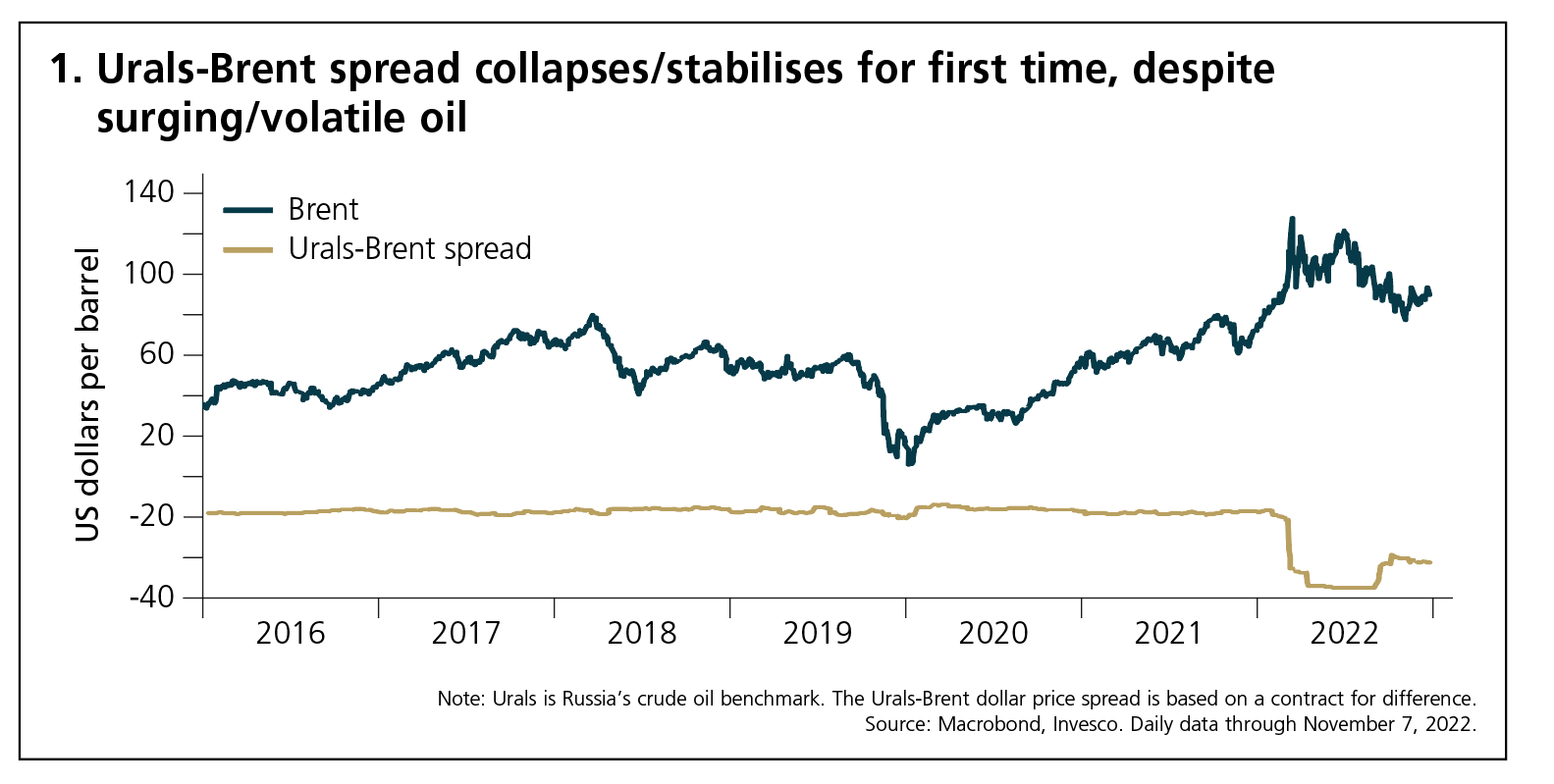

Pricing dynamics in Russia’s commodities trade suggest the dollar remains the main global unit of account. Consider Urals, the Russian crude oil benchmark, and Brent. The combination of sanctions and the public backlash against doing business with Russia led to an almost immediate segmentation in the global crude oil market. Figure 1 highlights how the Urals-Brent oil price spread was tight and somewhat procyclical – tending to narrow when oil prices rose and widen when they fell.

This changed after Russia’s invasion. For the first time, the spread collapsed even as the underlying global oil price skyrocketed. The spread has been relatively stable, even as underlying oil price benchmarks have continued to be volatile.

Thus, Urals now trades at a deep discount to the world price, which appears to be required for the rest of the world to buy Russian oil. The law of one price – any commodity trades globally at the same price – has been suspended by financial sanctions, trade barriers and western reluctance to ‘buy Russian’. However, the stability of the discount implies that Urals’ pricing still reflects the global dollar price of oil.

2. Global means of payment

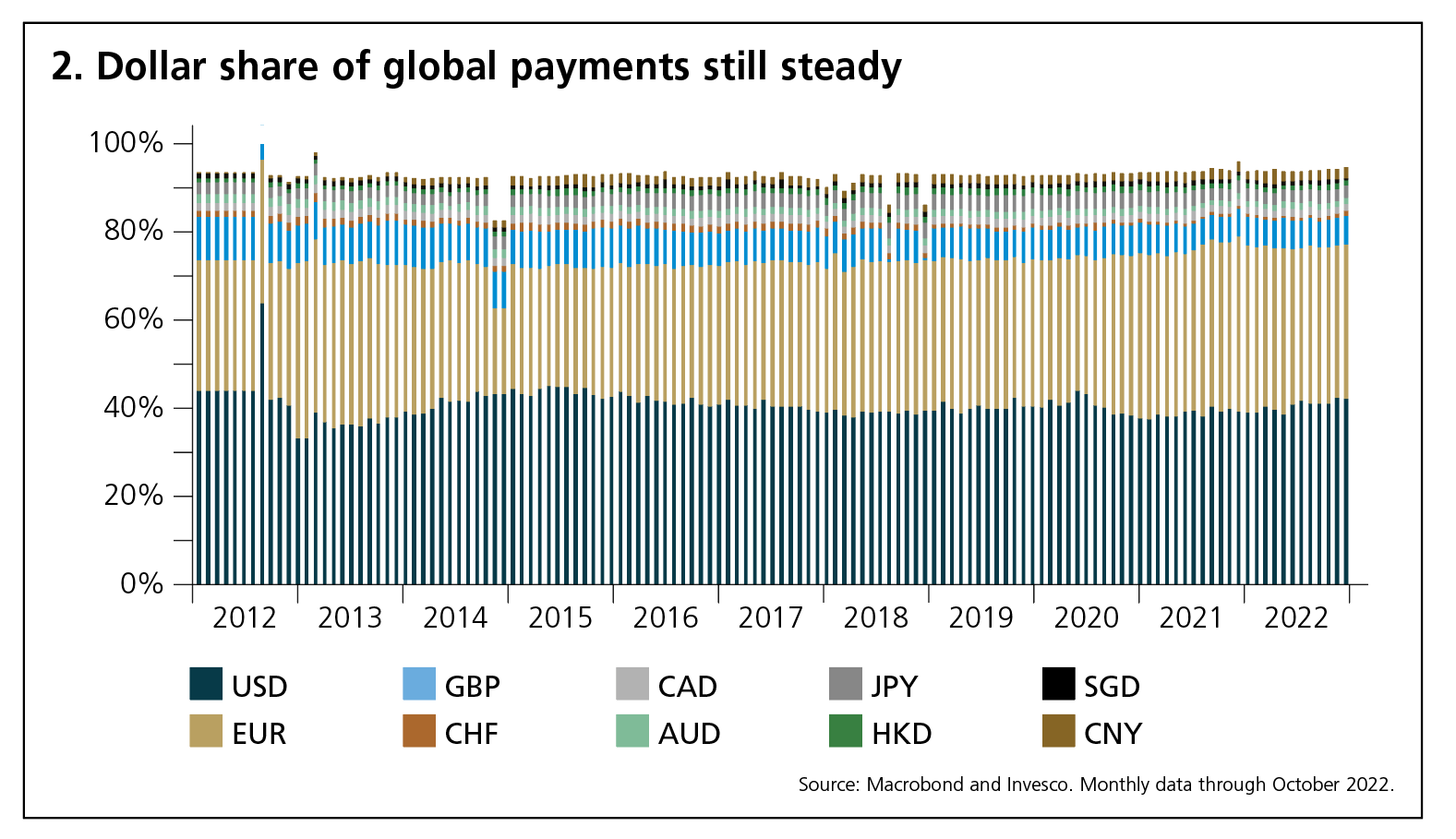

Anecdotal evidence and reports indicate that Russia is trading oil with China in renminbi, with India in rupees and with Turkey in rubles. Saudi Arabia is considering transacting with China in renminbi too. These shifts reflect the risk that Russian oil may yet be sanctioned. However, there is little evidence of a major shift in the means of payment – at least so far. Figure 2 shows that the dollar continues to retain a roughly stable 40% share of global payments. The euro has well in excess of 30% – even though key commodities such as oil and others are priced in dollars, and even though the share of the dollar in official FX reserves remains close to 60%.

3. Store of value

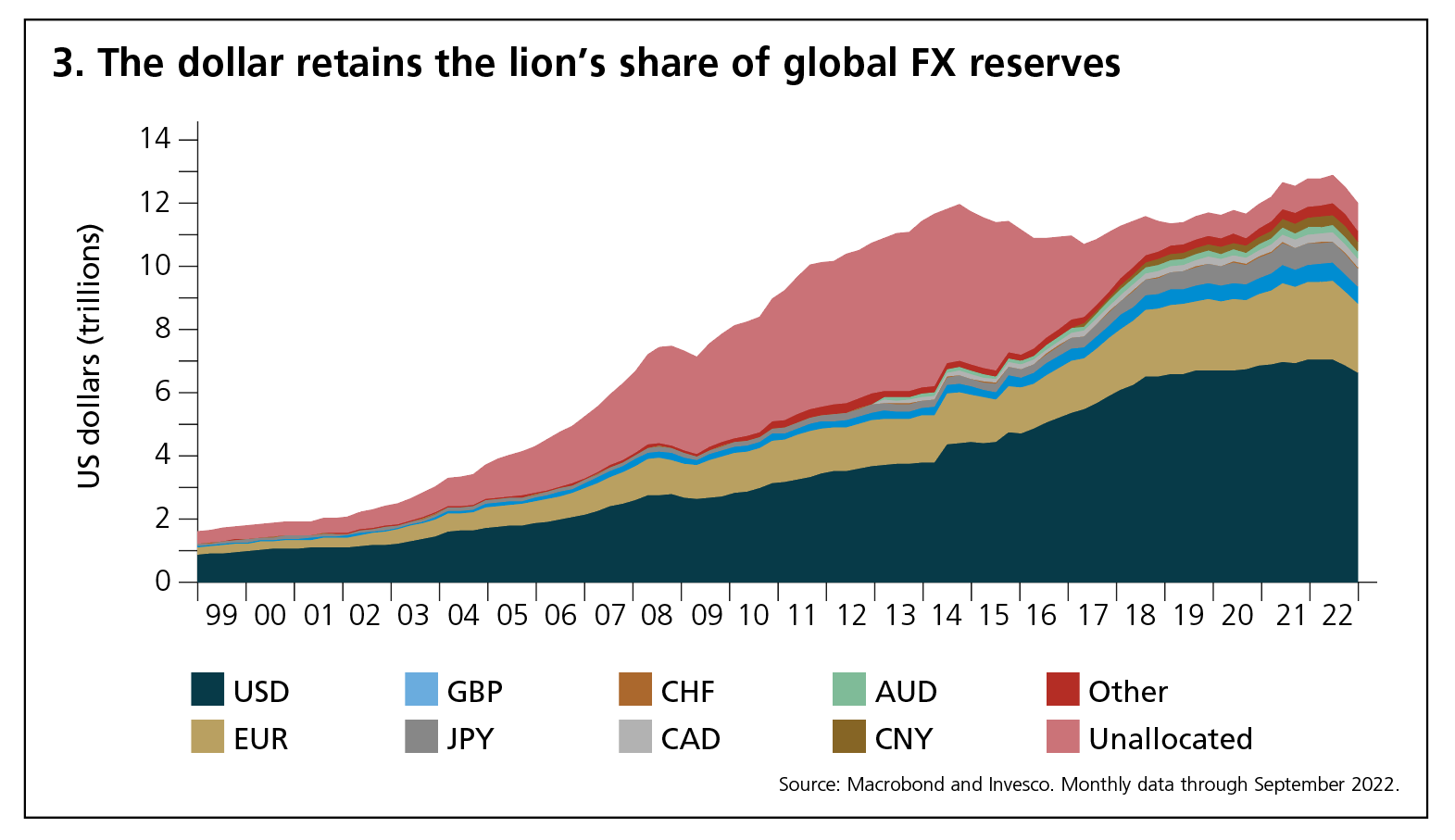

As figure 3 shows, the dollar continues to dominate global FX reserves, with a market share of around 60% – far in excess of the US share of global payments (40%) of global GDP (now below 20%) and of most other measures such as world trade.

Therefore, the dollar’s reserves share continues to punch far above the US weight in the world economy. Yet the dollar’s share of global reserves may well reflect the scale and depth of US financial markets more than the US weight in global economic activity, trade or corporate capital expenditure (capex). Sixty per cent of global FX reserves may be more commensurate with US financial dynamism and market capitalisation and may be appropriate, since central bank intervention must address both trade and financial shocks – and financial flows tend to be larger and faster-moving than trade or capex-related flows.

Will the US dollar remain a global problem?

When the US broke the Bretton Woods Treaty in 1973, the then US Treasury Secretary John Connolly infamously quipped: “The dollar is our currency, but it’s your problem,” reflecting the reality of the currency’s exceptional position in the international system. Other major economies and academics have looked for a fall in this “exorbitant privilege” for decades.

The euro and, recently, the renminbi have been tipped as contenders for the dollar’s currency crown. However, it is clear the euro faces a structural problem, lacking a fully fledged fiscal union to match its monetary union. Though there have been occasional steps towards fiscal union during the eurozone sovereign debt crisis and the Covid-19 pandemic, these are neither comprehensive nor sufficient, but ad hoc responses to crises. Further existential crises cannot be ruled out, which may or may not lead to further fiscal integration. Hardly the stuff of a global public good – an international, perceived safe reserve asset, especially when domestic perceived safe assets within the eurozone remain fragmented across member-state fiscal and financial systems, and still constitute a potential bank/sovereign ‘doom loop’. Plus, the war has highlighted once again that the eurozone and European Union rely on the US for global co‑ordination, security and even economic support – in this case through energy exports.

The renminbi has become an arguably more viable alternative to the dollar than the euro, given China’s global economic heft and trade/investment relationships with many other major reserve-holding countries. However, China retains resident capital controls, which implies that neither interest rates nor the exchange rate represent market-clearing levels. Furthermore, other major reserve holders – Japan, India, the Republic of Korea, Switzerland and Norway – may be reluctant to shift their trade/payments/reserves from dollars to renminbi, given their trade/investment/security relationships with the US.

Despite all of this, many governments clearly wish to insulate their own trade, payments and economy from the potentially erratic America-first, conceivably isolationist or even multilateral western goals. Parallel systems may lie ahead instead of creeping replacement of the dollar: multiple means of payment co‑existing with a dollarised unit of account/store of value for intervention or investment. Such a mix may well suit a multi-polar new world order in which the US remains financially primus inter pares, even if not economically or geopolitically dominant.

This may seem bizarre, but it’s worth recalling that such parallelism actually persisted for much of the Cold War. The western world had a dollar-dominated cross-border system. Meanwhile, the USSR operated a domestic ruble system and a separate international system of ‘clearing rubles’ to conduct trade and payments with its ‘client states’ – some of which were within its sphere of influence, while others were in the non-aligned movement. Perhaps the world will go back to the future in the international monetary system, given rising geopolitical and geoeconomic tensions.

Investment risks

The value of investments and any income will fluctuate (this may partly be the result of exchange rate fluctuations) and investors may not get back the full amount invested.

Important information

This content is for Central Banking Journal only and is not for consumer use.

Where individuals or the business have expressed opinions, they are based on current market conditions, they may differ from those of other investment professionals and are subject to change without notice.

Published by Invesco Asset Management Limited, Perpetual Park, Perpetual Park Drive, Henley-on-Thames, Oxfordshire, RG9 1HH, UK.

Authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority

Sponsored content

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com