This article was paid for by a contributing third party.

Official reserve management in the 21st century

A lack of operational clarity and reluctance to view reserve portfolios holistically have prevented optimal, rules-based approaches to reserve management becoming commonplace. BlackRock‘s Terrence Keeley, Stuart Jarvis and Michael Palframan explain how to promote optimality by observing the right principles.

The principles of best practice in official reserve management are no longer contested. Subject to strict liquidity and volatility constraints, foreign exchange reserves are to be managed against viable, risk-aware return objectives. In actual practice, however, this deceptively simple paradigm has proven difficult to implement. Three reasons explain this:

A lack of operational clarity about objectives

For years, reserve managers sought ‘safety’, ‘liquidity’ and ‘return’ without specifying what these competing goals meant over widely variant market conditions. Safety from what, exactly – default, reputational risk, capital loss, marked-to-market loss? Rather than quantifying each risk, summing them up in a portfolio context and ultimately assessing what return paradigm might justify bearing them, an overreliance on government bonds has been more often assumed.

As with defining safety, assessing how much liquidity reserve managers need to keep on hand has proved challenging. Are three months of imports, Guidotti‑mandated debt coverage and/or some component of M2 the right metric? And what is meant by liquidity, anyway? If immediate translation to cash and cash equivalents is sought, a wide array of asset classes would qualify, including indexed equities and many exchange-traded funds. Without a rigorous approach to one’s liquidity and volatility constraints, optimising returns becomes impossible. Optimisation requires deliberate balancing between competing objectives. In short, many central bank reserve managers have left a number of complex, but eminently solvable, problems to chance.

A failure to view reserve portfolios holistically

The second reason optimal, rules-based approaches to reserve management have not become the norm stems from a reluctance to view reserve portfolios holistically. Most investors – institutional and individual – consider the safety of owning asset classes such as equities or securitised debt to be independent of their broader portfolio implications. This precludes appreciation of how additional, uncorrelated exposures may reduce the volatility of a portfolio overall. Safety should be understood as reduced volatility. To put this in a reserve management context, consider a euro‑denominated reserve portfolio that holds nothing but German Bunds – an asset class many wrongly denote as being ‘risk-free’. Despite the fact that most Bunds bear negative yields (implying the certainty of loss) and are extraordinarily volatile (10-year Bunds have had a standard deviation of 4.6% in the past two years) such a portfolio is wrongly considered ‘safe’ because of its low probability of default. Meanwhile, combining Bunds with the Dax Performance Index or some other uncorrelated asset would substantially lower that portfolio’s overall risk while enhancing return prospects over a defined time horizon. If there is one paradigmatic lesson reserve managers still need to take on board, it is that asset classes that are truly uncorrelated can reduce the volatility of a portfolio, especially relative to more of the same, presumed risk-free assets.

Forex reserve volumes

The final reason many central banks struggle to employ optimal reserve management stratagems relates to the volume of forex reserves held in the first place. This decision is often beyond a reserve manager’s purview since finance ministries usually set exchange rate policies. This doesn’t alter their risks, however. The biggest exposure most central banks incur from their reserve portfolios is foreign currency translation risk; axiomatically, excess reserves necessitate excess currency risk borne by the sovereign and, ultimately, the public. As approximately 65% of reserves are held in US dollars, weakness of the greenback means painful marked-to-market losses, particularly in many emerging market countries. Negative carry on those assets further highlights the need to own only as many reserves as are genuinely useful. The broad, historic movement from fixed- to floating-exchange regimes in recent decades might have been accompanied by a decline in forex reserves overall – yet they have continued to rise at more than a 6% annualised pace according to the International Monetary Fund. While many central banks accept they should optimise returns of their reserves subject to liquidity and volatility constraints, they often bear more forex risk than is justified relative to their needs simply because their forex reserves are too large.

Closing the gap between actual and best practice

Legendary baseball catcher Yogi Berra once said “in theory, there is no difference between practice and theory – but in practice, there is”. Operationalising optimal reserve management theory has been a hallmark of BlackRock’s advisory services for central banks for years. Over the past decade, BlackRock has helped dozens of central banks design and achieve more deliberate outcomes by co-engineering liquidity and volatility-constrained reserve portfolios against desired income objectives.

Clarity around objectives is a precondition for all successful portfolio construction. As reserves increase in size, central banks discover that their focus on liquidity needs is diminished by the desire to generate higher returns in a risk-aware manner. For this reason, many reserve managers split their reserves into tranches: one for short-term liquidity and one focused on longer-term return generation.

While it is possible to manage the portfolio as a whole rather than splitting it into pieces, it turns out dividing reserves into tranches has significant governance benefits. Different tranches have separate, defined objectives against which they can be measured and managed. Moreover, tranching makes it easier to respond to changes in the size of one’s reserves; rather than continuously recasting the balance between liquidity and return at the total portfolio level, one merely adds or subtracts between the two portfolios.

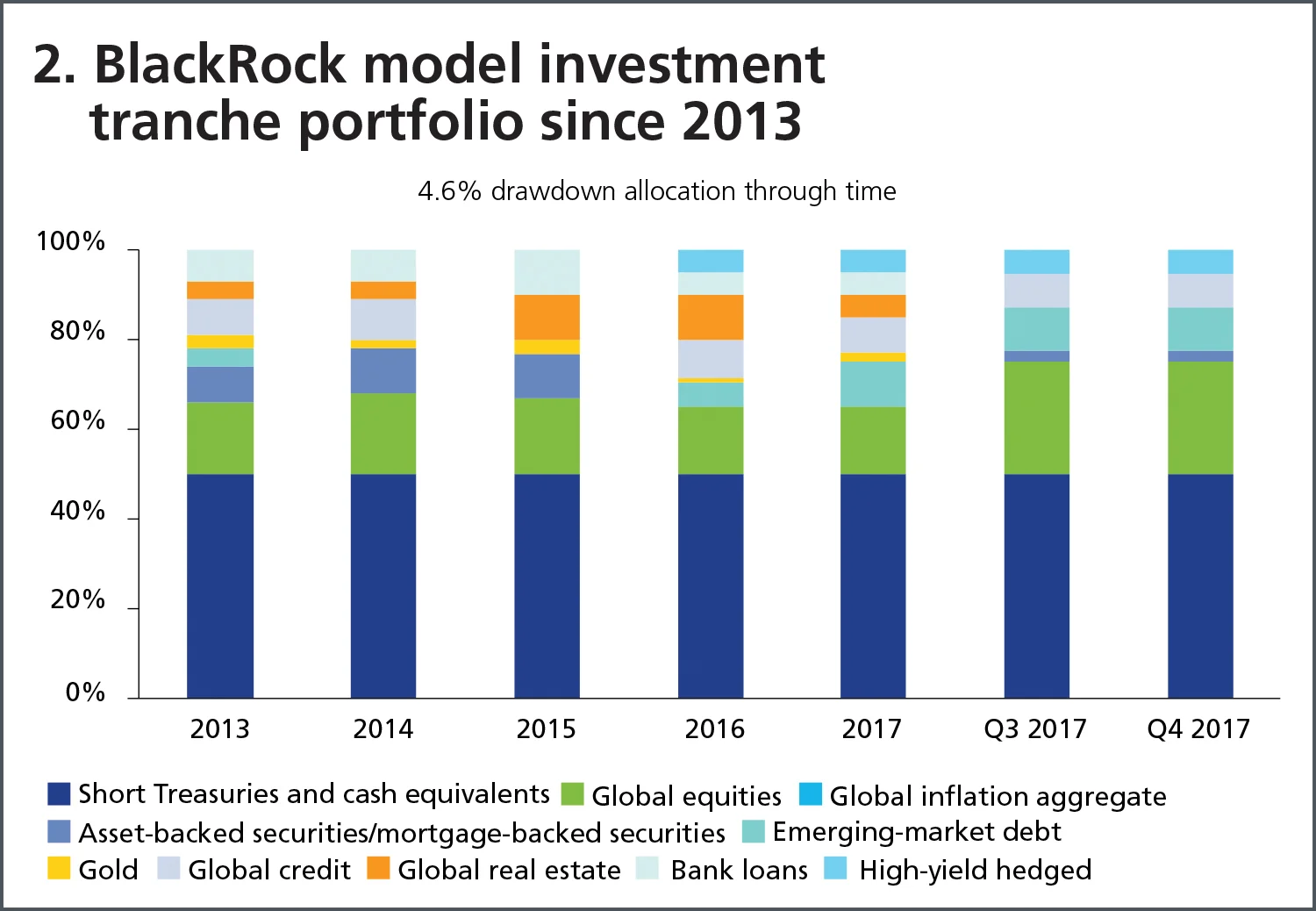

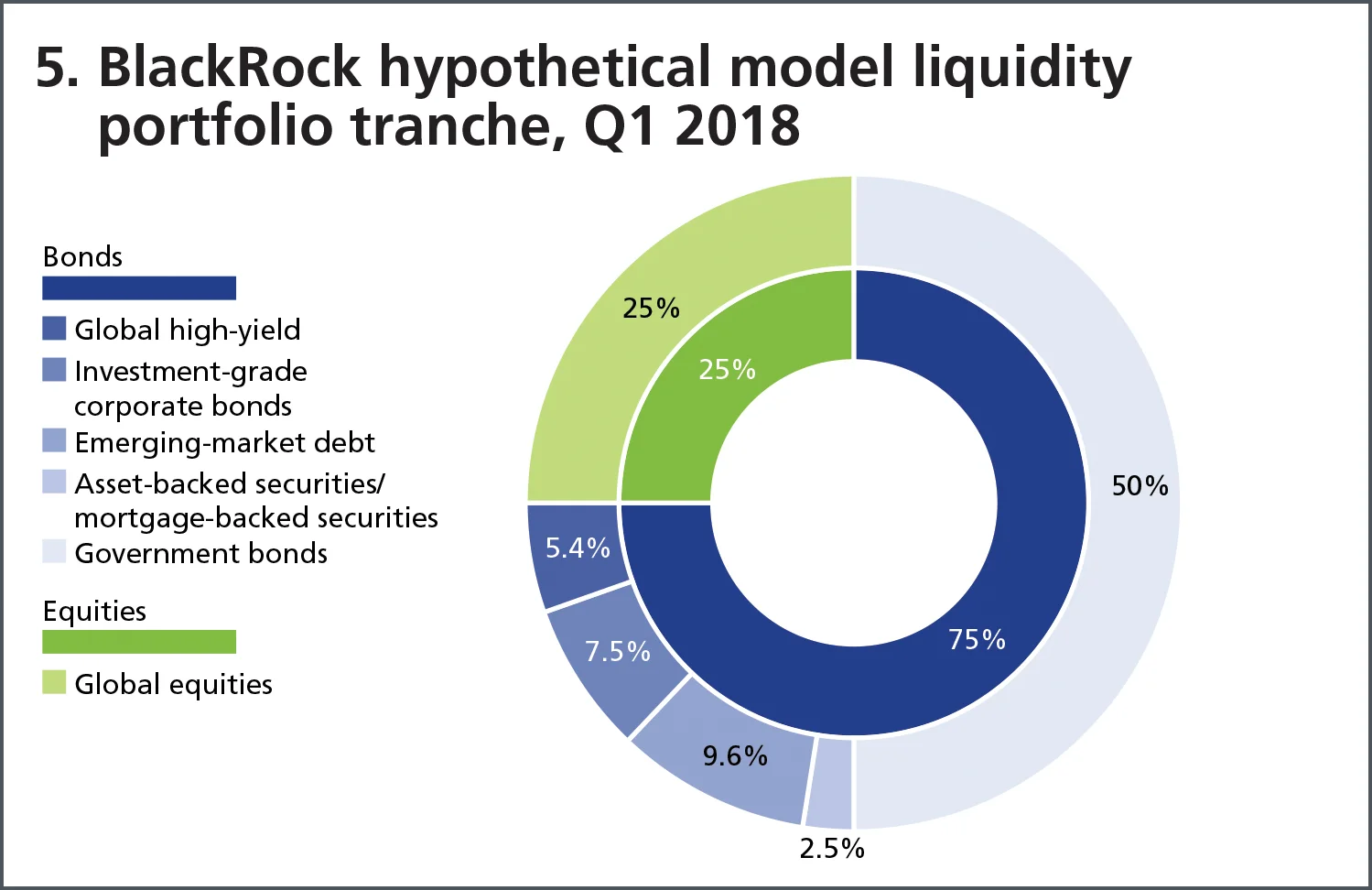

To illustrate how this construct works in practice, BlackRock has created and published model central bank reserve portfolios since 2013. The evolution of these portfolios is illustrated in figures 1 and 2. The model liquidity and investment tranches are constructed with a minimum 50% allocation to government bonds, and with a 2.5% return target and 4.6% drawdown constraint, respectively. We don’t suggest this is the right risk/return profile for every reserve manager; rather, we want to show that differing, realistic objectives can be attained when thoughtfully pursued.

BlackRock started this reserve manager portfolio exercise in 2013, when the rate environment was especially challenging. This meant that achieving the desired 2.5% return in the liquidity portfolio required greater risk exposures. As rates have been rising in recent years, the need to commit capital away from short‑duration fixed income has diminished, as highlighted by the changing allocations in figures 1 and 2.

For the model investment portfolio (figure 2), BlackRock has also advocated asset allocation shifts. In this case, more capital has been allocated towards equities in recent years. This is a function of the lower volatility environment offering an attractive opportunity to capitalise on equity returns while not compromising on volatility.

Figure 3 presents the performance of these portfolios over time, compared with a portfolio of Group of 7, one- to 10‑year government bonds – a typical naive portfolio for forex reserves. As illustrated, the portfolios have delivered returns in excess of the government bond index, while maintaining a 50% liquidity weight and their respective volatility constraints. Since inception, in fact, BlackRock’s model liquidity portfolio has exceeded its benchmark by 30 basis points, with +2.82% annualised performance. Meanwhile, our model investment tranche portfolio has achieved an annualised return of +3.67% with a realised volatility of 3.05%. Both portfolios compare favourably to historical reserve portfolios. Most importantly, both met our desired liquidity, volatility and return objectives.

Examining the performance for the nine months to the end of March 2017 in isolation, the volatility environment was rather muted. This led to stronger gains within the model investment tranche portfolio (+2.76%), partly due to allowing riskier assets such as equities. The 1.17% return from the liquidity portfolio, while lower than its 2.5% per annum target, was still greater than the 0.7% return of the G7 government bond reference index, but not as impactful as the higher‑volatility strategy.

Since 2017, these model portfolios have been updated on a quarterly basis and are freely available at BlackRock’s website. Please note our model liquidity and investment reserve portfolios, presented in figures 4 and 5, are now reviewed and updated on a quarterly basis by the BlackRock Investment Institute. Assessing these portfolios more frequently than in the past should allow for a greater ability to react as market events unfold. Quarterly updates also better reflect the practical process of the typical reserve manager. BlackRock’s website further describes the views that drive its return forecasts, providing detailed, comprehensive analytics on the risk drivers of its model portfolios.

Conclusion

Forex reserves perform a number of essential functions. At the most basic level, they provide confidence in monetary, debt service and exchange rate policies. They also limit external vulnerabilities during times of crisis by buoying confidence more generally. Central banks must manage their reserves in ways that make them readily deployable for these essential purposes while not ignoring return objectives. We believe BlackRock’s aforementioned model liquidity portfolio serves as a useful reference for reserves held for these exigent purposes.

Once a sovereign’s liquidity needs have been properly assessed and reserved for, heightened focus on return becomes both more plausible and optimal. In these circumstances, BlackRock’s model investment portfolio may serve as a more relevant benchmark. While the merits of a paradigm shift in optimal reserve management are demonstrably clear, implementation is not without its challenges. Buy-in and approval is required from a variety of stakeholders, not the least of which are governing boards and the public at large. A strong governance framework and clarity of mission, including benefits and risks, is essential.

For this reason, BlackRock’s reserve management advisory efforts remain focused on promoting practical solutions defined by every country’s unique circumstances and objectives. While no single design is optimal for everyone, optimality is available to all as long as the right principles are observed.

Sponsored content

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com