To play the counterfeiter

A Copenhagen research centre helps central banks to counterfeit their own banknotes to reduce fraud

Despite entering the digital age, important developments are taking place in the area of physical currency. Notably, two major central banks, the Swiss National Bank (SNB) and the Bank of England (BoE) are launching new currency series this year. These notes will include new security features and substrate alternatives, and some of these features are being put to the test at a little-known centre in Denmark, the Reproduction Research Centre (RRC).

The SNB has already launched the first of its hybrid notes in its latest series, combining a number of different security features into what one expert claimed was "one of the best polymer notes in the world". Meanwhile, the Bank of England will launch the first of its new note series in the third quarter – a £5 note bearing the face of Sir Winston Churchill.

New BoE notes

Many details surrounding the security features of the new BoE notes are being kept under wraps until the final design is announced on June 2 – and some elements might not emerge for decades to come. But the British central bank is expected to invest in some completely new security features.

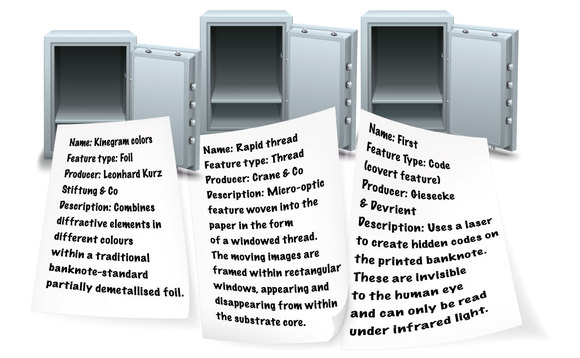

One area central banks have focused on in the past decade is the use of colour. This has reached new levels of complexity in the past couple of years. For example, security foil producer Leonhard Kurz Stiftung and Co offers a product called ‘kinegram colors’, which it describes as a new foil technique that combines diffractive elements in different colours within a traditional banknote-standard, partially demetallised foil. Kurz has claimed the kinegram colors technique is “virtually impossible to simulate or counterfeit”. That is because a person looking at a note using the foil technology would see the expected image with its metal and transparent areas in multiple colours, but the colours would vary depending on which side of the note is viewed. Kurz has previously stated that “a large, important central bank has selected kinegram colors technology to be used on their future series of banknotes”.

The use of shifting colours, both in print and thread, first became an important feature of banknote security after Romania introduced a colour-shift thread in the early 1990s. For example, between 2011 and 2015, 131 issuing authorities from countries ranging from Angola to Thailand issued newly designed or upgraded banknotes, with a total of 286 individual denominations, according to banknote printer De La Rue. And colour changing was the dominant security feature of choice across these families.

“The short answer is that they work – the public recognises them. But they are also robust in circulation, and can be combined with magnetics, for machine readability, and fluorescence. They offer design flexibility and can be easily integrated,” says a senior manager in De La Rue’s currency division.

Merging highly technical elements of banknotes is also an important consideration – a development that has coincided with increased use of polymer substrate notes. It is expected that combining new security features on Innovia polymer substrate notes will reduce the ability of counterfeiters to create viable fakes of the UK’s new notes. The BoE’s currency team, led by chief cashier Victoria Cleland, has also ensured the UK’s new banknotes – the £10 will be launched in 2017 and the £20 in 2020 – have undergone rigorous testing to ensure they are hard to copy.

Some of this work was done at the low-key RRC housed at the National Bank of Denmark – a lab set up to investigate the resistance of banknotes to currency-counterfeiting techniques – which does not allow access to non-members. All of the features on the BoE notes, as well as the substrate itself, were put to the test at the centre prior to securing final design approval.

Creating custom counterfeits

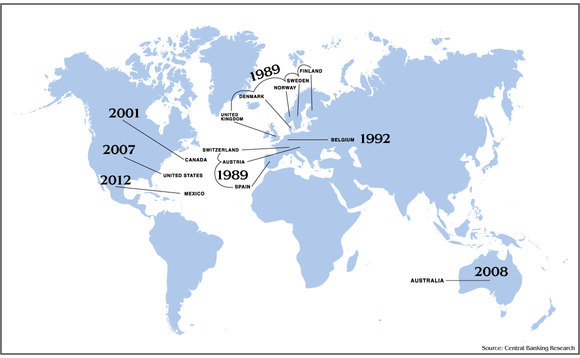

Staffed by only three full-time technicians throughout the year, the main purpose of the centre – formed by eight central banks1 in response to the growing availability of colour copiers and scanners in the 1980s – is to offer facilities to "investigate the possibility to imitate security features that are used or intended to be used on banknotes, by using commercially available equipment and materials", according to Jan Binnekamp, chair of the executive committee at the RRC.

Cleland at the BoE says it was especially helpful for central banks to attempt to make their own counterfeits when designing new currency series. "How long does it take to recreate? How much would it cost? What equipment is needed? How authentic are the results? These are all questions that need to be addressed," she explains.

The year member country central banks joined the Reproduction Research Centre

The year member country central banks joined the Reproduction Research Centre

(Note: The Netherlands Bank did not reveal when it joined the RRC)

The specific activities undertaken at the RRC, which has subsequently added six non-founding members, are kept under wraps with members bound to a confidentiality agreement. Some members refuse to disclose when they last used the centre and what impact the centre's work had had on their currency research. But the work is viewed as highly valuable.

"It is a really helpful tool for testing the ‘most appropriate' security features almost to destruction," Cleland says. "We did spend some time at the RRC testing the polymer – I went over there with one of my colleagues and spent a couple of days there. It is fascinating to see all the different types of equipment that can be used to try and counterfeit notes. The trip was a key part of our counterfeit resilience analysis."

Despite central banks being restricted in what they can disclose regarding how they test various features, clues as to what equipment is used can be gleaned from public sources. For example, a job advertisement for a permanent lab technician at the centre noted candidates would be expected to have experience with Adobe Illustrator and Photoshop, colour separation and graphic reproduction. They were also expected to be familiar with holographic foil applications, 3D printing and other digital printing methods, such as inkjet or laser printing.

As the banknote industry has evolved to create ever more advanced security features, the RRC has continued to test notes, with its methods of testing adapted to address new features. Binnekamp says the centre is now concentrating on machine-readable features in addition to its traditional focus on public security features such as watermarks, intaglio patterns, optically variable inks, foils and holograms.

Machine-readable features

There has been a surge in machine-readable features during the past decade. Banknote and currency security provider Giesecke & Devrient offers seven security elements relevant to machine reading, including a product called 'first' that uses hidden codes created by a laser, which are invisible to the human eye and can only be read under infrared light. It also provides a magnetic coding system that can be integrated into security threads.

The RRC provides central banks with significant resources to help them in their efforts to reduce counterfeiting. "What the RRC provides is a place with a lot of equipment," Cleland says. "There are a lot more ‘toys' to play with than if the Bank of England had to individually fund it; pulling all our resources together allows central banks to concentrate our efforts to reducing counterfeit numbers."

Collaboration is crucial

Co-ordination is also important, both between member central banks and their suppliers.

"The Bank of Mexico has benefited a lot from its membership to the RRC in regards to collaboration on the analysis of several banknote security features," says an official speaking on behalf of the general directorate of currency issuance at the Latin American central bank, which joined the RRC in 2012 and last used its facilities in September 2015. "We spend quite a lot of time talking to substrate suppliers and security feature developers to try and understand what new developments are available on the market," adds Cleland from the BoE.

The facilities at the RRC enable central banks to make sure security suppliers are producing features that are fit for purpose. "In some cases the central bank may invite their commissioned banknote printer to participate in the work. Security feature providers may receive feedback on the test results from their customers, but they are usually not involved in testing," says the RRC's Binnekamp.

Every year members of the RRC hold an annual meeting, chaired by one of the central banks – this year, Binnekamp from The Netherlands Bank (DNB) assumed the role. At the annual meetings, members report back their findings from their visits. There are also discussions regarding equipment: what has proved useful and what needs to be acquired in the future. "There's always some stuff needed, those are the secrets of the field. No-one will disclose any material or techniques; it's highly confidential," says Theodoros Garanzotis, director of research at the currency department at the Bank of Canada, when asked what equipment had been requested at the latest meeting.

The Bank of Canada has been a member of the RRC since around 2001, joining the original eight alongside Australia, the US and four other central banks. Each bank spends around two to three weeks a year at the lab – contributing an equal amount of money to undergoing projects, making sure the resources are allocated fairly. In 2012, the Federal Reserve spent $41,000 on the centre, representing 1% of the US's counterfeit-deterrence research budget.

While Garanzotis was unwilling to disclose when the Bank of Canada last used the lab, he did confirm "pretty much all" of the security features now used on Canada's Frontier Series launched in 2006 were tested at the RRC.

The Bank of Canada has also collaborated with other members on specific features. "Any member can invite other members to work together and pull their time, but it depends on where their common interests are and what security features they are planning to analyse," he says.

Another central bank that has benefited from the collaborative spirit honed at the centre is Norges Bank, which is due to launch its new series in the autumn of 2017. "In our case, as a small central bank with limited resources, it is very valuable to discuss and collaborate with other central banks," says Trond Eklund, director of the cash department at the bank.

Norges Bank's quest for security features began in 2012 when other countries in the region began plans to roll out new series. "Sweden, Denmark, the ECB, Switzerland and the Bank of England were all rolling out new series, there was a lot of development going on around us. We did not want to lag behind compared with countries in the region, we wanted to have the same level of security in our banknotes," Eklund adds.

New security features on the market

New security features on the market

Norges Bank is now coming to the end of its design process and will begin mass printing its first two denominations in mid-May, testing out its new security features that have yet to be made public. One of the key features will be the ‘rapid thread' made by Crane Securities – a micro-optic thread that provides easily detectable movements, noticed with just a "modest" tilt of the banknote.

This was one of the reasons Norges Bank opted not to switch to polymer substrates. "From our context, the main reason [we did not choose polymer] was the portfolio of security features for the paper notes," he says, explaining the new banknotes will use micro-lens technology, also made by Crane, alongside the new ‘rapid thread' and other security features.

Like the BoE and the Bank of Canada, Norges Bank has also extensively tested the new security features. "To mitigate risk, we have done many tests, for instance the rapid thread is a very new solution on the market so we produced test notes with these threads and checked their printability," he says. Part of this effort included attempts to counterfeit Norges Bank notes during the testing process.

Understanding the work counterfeiters do is important when central banks invest in more secure banknotes, "Counterfeit deterrence is a continuous contest between the issuing authorities (supported by the legitimate industry) and the counterfeiters," says Binnekamp. "Therefore, innovation and continuous improvement is a must in preserving the counterfeit resilience of banknotes."

1. Austria, Denmark, Finland, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK.

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@centralbanking.com or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.centralbanking.com/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. Printing this content is for the sole use of the Authorised User (named subscriber), as outlined in our terms and conditions - https://www.infopro-insight.com/terms-conditions/insight-subscriptions/

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. Copying this content is for the sole use of the Authorised User (named subscriber), as outlined in our terms and conditions - https://www.infopro-insight.com/terms-conditions/insight-subscriptions/

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com

Most read

- ECB says iPhone is currently incompatible with digital euro

- Supervisors grapple with the smaller bank dilemma

- Schnabel: ECB could replace central forecast scenario